by Eric Metaxas –

Martin Luther wanted to coax theologians into a debate on indulgences—not reset Christianity.

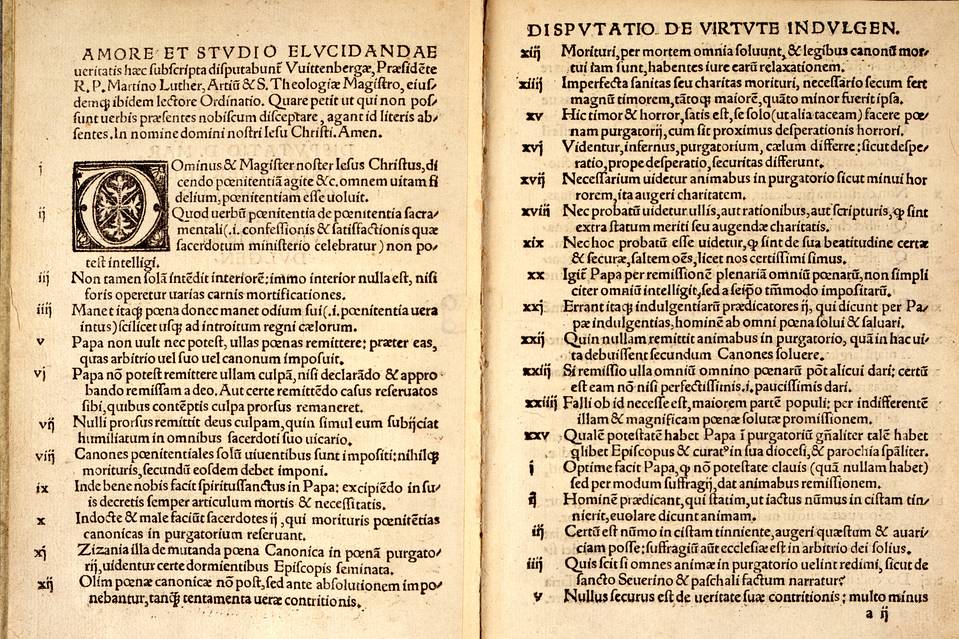

Martin Luther’s “95 Theses,” first published in 1517, now stored in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin. Photo: Bridgeman Images

This week the world celebrates the 500th anniversary of an event that never happened. Well, something did happen, and it altered the course of history. But what actually took place is astoundingly different from how it is portrayed today.

As the story is told, on Oct. 31, 1517, an Augustinian monk named Martin Luther socked the European church establishment in the kisser by defiantly nailing his “95 Theses” on indulgences to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The thunder of his hammer resounded throughout the world. It was as though he had stuck his finger in the pope’s eye.

The document brazenly charged the Catholic Church with corruption. The corrupt powers-that-be were put on notice that the vile practice of indulgences—whereby the faithful could throw a coin in the coffer to buy their way out of purgatory or worse—must end forever.

Except it never happened, at least not that way. Luther probably didn’t post his theses on the famous date celebrated each year, though he likely did within a month of the designated day. And they might never have been posted by Luther, despite five centuries of paintings depicting him doing just that. As it happens, he may have handed the document to a church custodian to post. And if Luther did post it himself, he may even have unheroically affixed it with paste.

More important, posting the document on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church was not an act of calculated defiance. That door had long served as the community bulletin board for anything and everything. For context, imagine the fabled document posted next to a flyer for a missing cat.

The most important difference between how most people remember the event and what actually happened is that the 30-something monk never dreamt that history would notice what he was doing. He did not intend to be defiant or to cause trouble. And he certainly did not plan to shake the foundations of the church he loved and obediently served. The idea that this all might lead to a sundering of the church was unthinkable. If he had thought of it, it would have utterly horrified him.

And the theses were written in Latin, which no one but cultural elites could understand. If there was anything provocative in what he wrote, it was only because such documents typically contained an edgy thesis or two in the hopes of instigating a robust debate.

The brainy Saxon monk merely wanted to coax his fellow theologians into an academic debate on indulgences, thinking that something might be done about the troubling practice through the proper and customary channels. What happened shocked Luther more than anyone.

A copy of the document was promptly delivered to Rome, where it furrowed Vatican brows and upset the papal stomach. Far worse, Luther’s well-meaning Saxon colleagues quickly translated the document into German. Then they duplicated it endlessly without his permission, courtesy of a relatively new technology invented by a fellow German, Johannes Gutenberg. Suddenly everyone was reading it across Europe and debating its points. Before Luther could say “sola scriptura,” the horse had slipped out of the barn and was wildly trampling the status quo that had existed for centuries.

Within four years, Luther’s written and oral responses to the growing conflagration had taken the world by storm and he arguably had become the first genuine celebrity in world history. The frothy torrent of writings that poured from his pen would make printers and publishers rich, with no royalties ever paid to him for his troubles. And his woodcut portraits reproduced like rabbits across the German landscape.

The powerful ideas Luther’s writings conveyed would in time lead to virtually everything we now take for granted in the modern world. By prompting the end of Vatican hegemony, Luther opened the door for the creation of thousands of new churches under dozens of denominations, Lutheran among them. In the coming centuries, this attitude would help elevate the concepts of religious pluralism, tolerance, democracy and freedom.

Who knew? Certainly not Martin Luther, whose grotesque pronouncements against the Jews near the end of his life proved that he simply did not comprehend the ramifications of what he had loosed upon the world.

But by humbly raising the questions he had in 1517, and then by responding to the attacks that followed as truthfully and carefully as he could, Luther ended up cracking the great edifice of medieval Christendom in twain. And for good and for ill both, out of that opening the future itself seemed to fly.

Mr. Metaxas is the author of “Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World,” just out from Viking Press.

Source: wsj.com

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online