By: Jay Cost – nationalreview.com – June 18, 2018

This week I had an opportunity to tour Montpelier, James Madison’s historic homestead located outside Orange, Va. If you have the opportunity, I highly recommend it. Unfortunately, most of Madison’s possessions have been lost — sold after he died to pay back the enormous debts that his stepson had accumulated. However, the curators of this museum have done painstaking, marvelous work to re-create it as it was during his retirement.

Interestingly, Madison kept portraits on the walls of both political allies and enemies — as a way to stimulate conversation with the endless stream of guests who called on him. A portrait of his political compatriot Thomas Jefferson hangs next to one of John Adams, who was of the opposite political party. I noticed during the tour that there was no picture of Alexander Hamilton, and the tour guide told me that in all likelihood the first secretary of the treasury never did adorn the walls of Montpelier.

That figures, I thought.

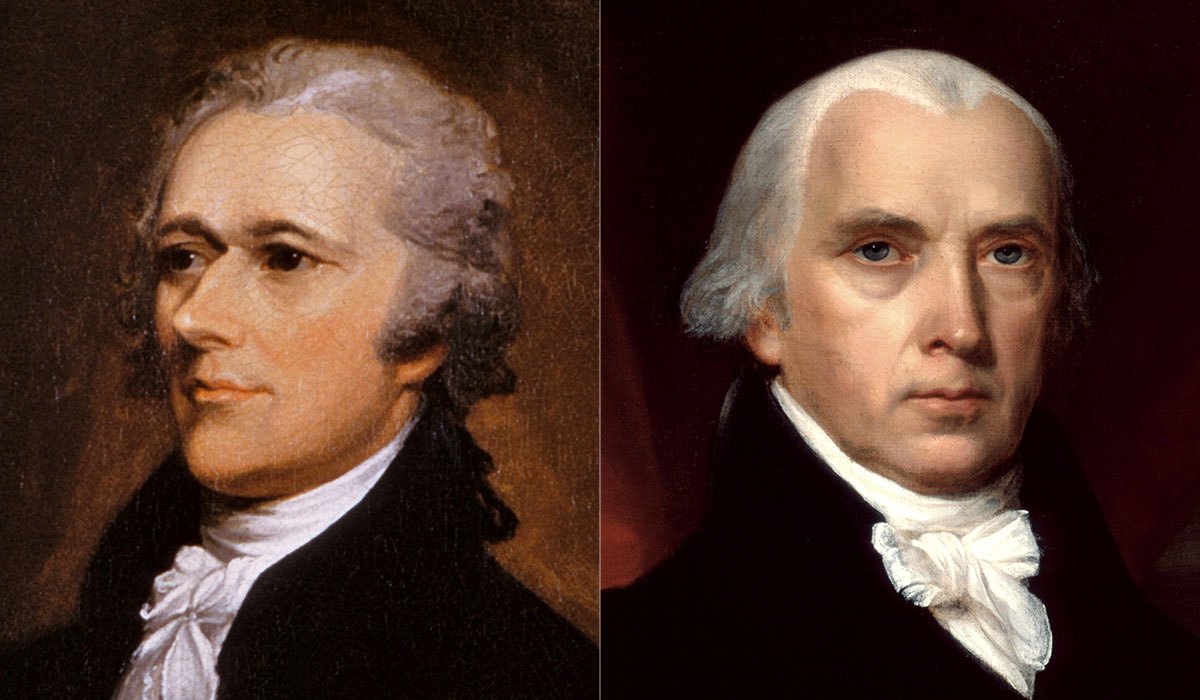

In the course of researching my new book, The Price of Greatness: Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and the Creation of American Oligarchy, I was struck by the level of mutual enmity and condescension that came to exist between the two men, even though they had worked together for years, laboring intensely to bring the Constitution into being. Their efforts, of course, culminated in the Federalist Papers, the series of essays they co-wrote under the pseudonym “Publius.” It is peculiar indeed to think that the two sides of Publius’s personality would come to hate each other, but that is what happened. Their relationship fell to pieces beginning in 1790, when Hamilton introduced his economic program. From that point on, the two of them were at odds, in what became a highly personal battle.

And while Jefferson and Adams became friends once more after they both had retired, I doubt very much that Madison and Hamilton ever would have had such a reconciliation, had Hamilton not been killed in a duel by Aaron Burr in 1804. Indeed, when James Monroe came to call on Eliza Hamilton at the end of his presidency, the widow of the late secretary refused even to receive him — so angered was she about the shoddy treatment her husband had endured, more than 20 years after his death.

I think there is quite a bit to learn from this complicated relationship between Madison and Hamilton, as I detail in the book. One point that I do not linger on in the text, but that is nevertheless worth mentioning, is how the two of them came to ascribe bad motives to each other. In Madison’s reckoning, Hamilton was a would-be monarchist who sought the destruction of the republic itself. By Hamilton’s measure, Madison was a fool, and a dishonest one at that, too quick to follow in the footsteps of Jefferson or genuflect to the political mood of Virginia, even when he knew the national interest required something else.

In so many ways, the Founding Fathers provide us with a model for statesmanship. Their leadership during the tumultuous years when the 13 colonies forged an independent nation serves as an inspiring call to greatness in ourselves. But not always. Sometimes, as in the case of Madison and Hamilton, they could be petty, mean-spirited, and selfish.

Even so, we can still learn something, at least from their error. Too often in our politics, we are willing to believe that our political opponents are not just wrong but bad (or evil), or at best fools. They want to destroy the America we know and love, we think, and replace it with some terrible alternative. Both Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives, have these sorts of views about each other. If you spend any time on Twitter, you know exactly what I mean.

From a certain perspective, this kind of contempt is a luxury of democratic politics. We can safely hate one another because the human impulse to resolve disputes by recourse to violence has been successfully constrained, at least for the most part. So we never actually follow through on the logic of our disregard — that if so-and-so is an enemy to the public interest, then we should not tolerate his continued participation in the body politics.

Nevertheless, the speed with which we imagine that our opponents have evil hearts or ignorant minds makes it harder to find common ground. What I found in my research on Madison and Hamilton is that, if you put aside their hatred for each other, you can see legitimate tradeoffs between their competing views of how the new nation should work. By the same token, I wonder if the Left and the Right could come together on issues, such as cutting down on corruption, if they could stop hating one another and appreciate that most of us are earnestly trying to figure out what is in the public interest.

Pie in the sky? Probably. Still, it was bittersweet to see that Montpelier was bereft of any memorial to a once-great team of statesmen, the mighty Publius who so carefully distilled the essence of the Constitution for generations to come. Similarly, one wonders what we might accomplish together if we stopped pouring spite on one another.

To see this article, click read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online