By: Gary Haugen and Victor Boutros – foreignaffairs.com – June 2010

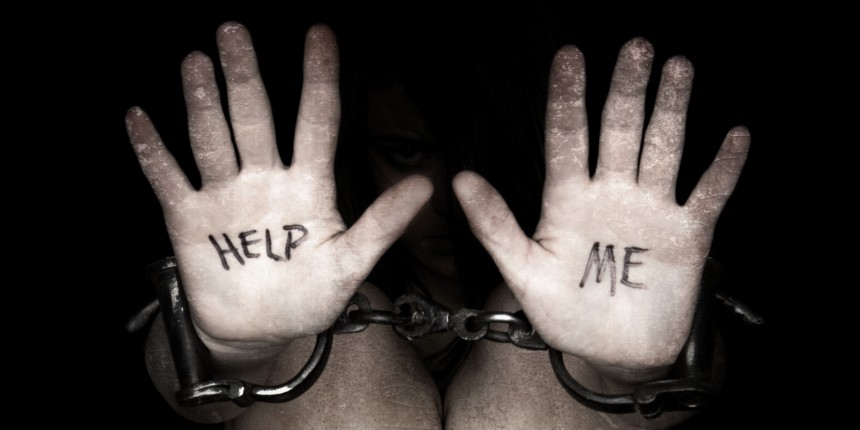

For a poor person in the developing world, the struggle for human rights is not an abstract fight over political freedoms or over the prosecution of large-scale war crimes but a matter of daily survival. It is the struggle to avoid extortion or abuse by local police, the struggle against being forced into slavery or having land stolen, the struggle to avoid being thrown arbitrarily into an overcrowded, disease-ridden jail with little or no prospect of a fair trial. For women and children, it is the struggle not to be assaulted, raped, molested, or forced into the commercial sex trade.

Efforts by the modern human rights movement over the last 60 years have contributed to the criminalization of such abuses in nearly every country. The problem for the poor, however, is that those laws are rarely enforced. Without functioning public justice systems to deliver the protections of the law to the poor, the legal reforms of the modern human rights movement rarely improve the lives of those who need them most. At the same time, this state of functional lawlessness allows corrupt officials and local criminals to block or steal many of the crucial goods and services provided by the international development community. These abuses are both a moral tragedy and wholly counterproductive to the foreign aid programs of countries in the developed world. Helping construct effective public justice systems in the developing world, therefore, must become the new mandate of the human rights movement in the twenty-first century.

COLD CASES

In a June 2008 report, the United Nations estimated that four billion people live outside the protection of the rule of law. As the report concluded, “Most poor people do not live under the shelter of the law”; instead, they inhabit a world in which perpetrators of abuse and violence are unrestrained by the fear of punishment. In this world, virtually every component of the public justice system — police, defense lawyers, prosecutors, and courts — works against, not with, the poor in providing the protections of the law. Take, for example, the police. For most of the world’s poor, the local police force is their primary contact with the public justice system. The average poor person in the developing world has probably never met a police officer who is not, at best, corrupt or, at worst, gratuitously brutal. In fact, the most pervasive criminal presence for the global poor is frequently their own police forces. A 2006 study in Kenya, for example, revealed that 65 percent of those citizens polled reported difficulty obtaining help from the police, and 29 percent said they had to make “extraordinary efforts” to avoid problems with the police in the past year. According to a 1999 World Bank study, poor people in the developing world view the police as a group of “vigilantes and criminals” who actively harass, oppress, and brutalize them. Making matters worse is that in the cases in which local police officers are inclined to protect the poor, they frequently lack the training, resources, and mandate to conduct proactive investigations. As a result, when faced with danger or a crisis, the poor do not run to the police — they run away from them.

When a poor person does come into contact with the public justice system beyond the police, it is frequently because he or she has been charged with a crime. With incomes for the global poor hovering around $1-$2 a day, the average poor person cannot hope to pay legal fees. Many countries in the developing world do not recognize a right to indigent legal representation, leaving those who cannot afford a lawyer to navigate the legal process without an advocate. This means that a local official — or, for that matter, anyone in the community — can make an unsubstantiated accusation against a poor person that could put his or her liberty at risk without legal representation.

This problem is made worse by the simple scarcity of lawyers in the developing world. The average person in the developing world has never met a lawyer in his or her life. In the United States, there is approximately one lawyer for every 749 people. In Zambia, by contrast, there is only one lawyer for every 25,667 people; in Cambodia, there is one for every 22,402 people. There are more lawyers in the New York offices of some major law firms than there are in all of Zambia or Cambodia. Of this small class of lawyers, prosecutors represent an even tinier subset — and some of these are not even trained lawyers, and others, much like the police, extract bribes to drop cases. When cases are reported and referred for trial, there are frequently too few public prosecutors to handle the volume. This creates an enormous backlog, allowing cases to languish indefinitely on overloaded dockets.

Some experts, for example, have estimated that at the current rate, it would take 350 years for the courts in Mumbai, India, to hear all the cases on their books. According to the UN Development Program, India has 11 judges for every one million people. There are currently more than 30 million cases pending in Indian courts, and cases remain unresolved for an average of 15 years. Someone who is detained while awaiting trial in India often serves more than the maximum length of his or her prospective sentence even before a trial date is set. The International Center for Prison Studies at King’s College London found that nearly 70 percent of Indian prisoners have never been convicted of any crime. Even those who are not held in custody before trial face difficulties: some courts are so far away that it is too costly or logistically challenging for the poor to reach them, and the cases are decided in their absence. In India, like in many countries in the developing world, judges and magistrates sometimes solicit bribes in exchange for favorable verdicts or, in other cases, to continue the case indefinitely. Some courts do not even have access to the applicable legal texts, and judges consequently reach decisions without consulting the relevant legal standards.

In communities where de facto lawlessness reigns, even if a poor person is aware that he or she is being illegally abused, it is unlikely that such a person has ever seen a law against such abuse enforced on behalf of someone of similar social status. On the contrary, a poor person in the developing world is far more likely to know someone who has been a victim of the public justice system than a beneficiary of it. As a result, the idea of “law enforcement” is not one of the social mechanisms that most poor people in the developing world consider useful for navigating the threats of daily life.

A THIRD ERA?

The modern human rights movement began in the years following World War II, when a number of scholars and diplomats began an effort to articulate and codify international standards on fundamental rights. Documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights — as well as conventions on discrimination, torture, children’s rights, and women’s rights — are the products of this movement. Over time, it produced a body of rights and norms to which all people of the world can lay claim. This work continues today, as international organizations and countries draft and amend treaties, conventions, and protocols that obligate states to extend fundamental legal protections to those within their borders.

If the first stage of the modern human rights movement was largely intellectual, the second was political. During this stage, the movement worked to embed the growing body of international norms into national law. Individual governments throughout the developing world began to enact reforms that protected political, civil, and economic rights. South Asian countries, for example, passed laws outlawing bonded slavery; African countries threw off centuries of traditional cultural practice and gave women the right to own and inherit land and to be free of ritual genital mutilation; Southeast Asian governments elevated the status of women and girls, creating new laws to protect them from sexual exploitation and trafficking; and Latin American countries adopted international standards for arrest and detention procedures and codified land reform rights. As a result of this global political movement, hundreds of millions of vulnerable and abused people became entitled to global standards of justice and equity under local law.

The tragic irony, however, is that the enforcement of these rights was left to utterly dysfunctional national law enforcement institutions. Most public justice systems in the developing world have their roots in the colonial era, when their core function was to serve those in power — usually the colonial state. As the colonial powers departed, authoritarian governments frequently took their place. They inherited the public justice systems of the colonial past, which they proceeded to use to protect their own interests and power, in much the same way that their colonial predecessors had. Rather than fulfill the postcolonial mandate of broad public service, the police and the judiciaries of the developing world often serve a narrow set of elite interests. The public justice systems of this part of the world were never designed to serve the poor, which means that there is often no credible deterrent to restrain those who commit crimes against them.

In the absence of functioning justice systems, the private sector has developed substitutes: instead of relying on the police for security, companies and wealthy individuals hire private security forces; instead of submitting commercial disputes to clogged and corrupt courts, they establish alternative dispute-resolution systems; and instead of depending on lawyers to push legal matters through the system, those with the financial means may seek and, in some cases, purchase political influence.

Without pressure from other powerful actors in society, elites have little or no incentive to build legal institutions that serve the poor. A properly functioning legal system would only limit their power — and require a substantial commitment of financial and human resources. At the moment, they see no serious benefits to justify the effort: for them, a functioning public justice system might, in fact, be a problem.

Two generations of global human rights efforts have been predicated — consciously or unconsciously — on assumptions about the effectiveness of the public justice systems in the developing world. But those systems clearly lack effective enforcement tools; as a result, the great legal reforms of the modern human rights movement often deliver only empty parchment promises to the poor. In large part, the human rights community — which includes various UN bodies and agencies, government offices, nongovernmental organizations, and individual jurists and scholars — exists to defend the victimized, particularly where more powerful actors have little incentive to act on their behalf. Yet throughout the history of the modern human rights movement, this community has largely neglected the task of helping build public justice systems in the developing world that work for the poor.

THE HIGH COSTS OF LOW ENFORCEMENT

[. . .]

PULLING UP SHORT

[. . .]

CASEWORKERS FOR THE POOR

[. . .]

To see the remainder of this article, click read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online