By: Nicholas Phillips – nationalreview.com – February 1, 2019

Few Americans identify as fiscally conservative and socially progressive. So why does Howard Schultz think such a platform will win him the presidency?

Howard Schultz, the former CEO of Starbucks, is preparing to run for president. But he’d like you to know that he would be no ordinary candidate — he would run as a “centrist independent.”

Schultz thinks that his candidacy is viable because 40 percent of American voters self-identify as independents. Neither party, he says, represents the “silent majority of the American people.” From his perspective, the increasingly acute split between the two parties means that many disaffected Republicans and Democrats are “looking for a home,” and Schultz wants to invite you to his guest house. Like Michael Bloomberg, he opposes the “extremes” of both parties: He’s a fiscal disciplinarian who rejects the Left’s lavish spending proposals on health care and college, but he’s also a social progressive who breaks with Republicans on issues such as immigration.

Schultz’s perspective, of course, is a billionaire’s perspective. And if a billionaire feels politically homeless, it’s because he, like legions of finance and tech bros in Brooklyn and Palo Alto, is “socially liberal but fiscally conservative.” Neoliberal, in a word: a big fan of free markets, but an equally big fan of diversity, progress, and sustainability. Suspicious of socialism, but woke — some might say performatively so — on immigration, LGBT issues, racial justice, and abortion. When a billionaire with a platform or a yuppie with a Patagonia fleece vest tells you he’s a “centrist,” or an “independent,” or a “moderate,” this is what he means.

But what Schultz means by “centrist” is most definitely not what almost everyone else means when they report dissatisfaction with the two major parties. The vast majority of Americans who don’t fit into either party box aren’t neoliberals — they’re populists, the exact opposite of “socially liberal but fiscally conservative.”

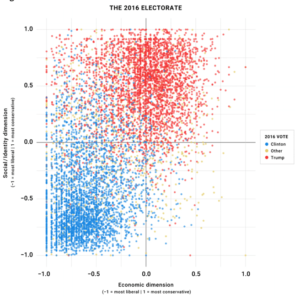

In a remarkable report for the Voter Study Group titled “Political Divisions in 2016 and Beyond,” political scientist Lee Drutman plotted a nationally representative political opinion survey of the 2016 electorate on an X–Y graph, with the X axis representing economic views and the Y axis representing social views. The result looks like this:

Voters who are conservative on both economic and social issues are plotted in the upper-right quadrant, and voters who are liberal on both economic and social issues are plotted in the lower-left quadrant. Color-coding each voter with their choice in the 2016 election shows that voters in the upper-right overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump, and voters in the lower left overwhelmingly voted for Hillary Clinton. That makes sense: These are the voters whose views are well represented by the platforms of the two major parties.

Voters who are conservative on both economic and social issues are plotted in the upper-right quadrant, and voters who are liberal on both economic and social issues are plotted in the lower-left quadrant. Color-coding each voter with their choice in the 2016 election shows that voters in the upper-right overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump, and voters in the lower left overwhelmingly voted for Hillary Clinton. That makes sense: These are the voters whose views are well represented by the platforms of the two major parties.

But the real story is happening in the two quadrants whose views aren’t represented by Republicans and Democrats. The lower-right quadrant is where you end up if you’re “socially liberal but fiscally conservative,” like Howard Schultz. That quadrant is a ghost town, representing a mere 3.8 percent of the electorate. Meanwhile, the upper-left quadrant — those voters who are socially conservative but liberal on economic issues — is packed. A full 28.9 percent of the electorate resides in what Drutman calls the “populist quadrant,” outnumbering even the conservatives in the upper right, who clock in at 22.7 percent.

If you’re in that quadrant, you might be frustrated by the Republicans’ embrace of corporate tax breaks and spending cuts, but you’re probably also wary of Democrats who want open-door immigration and rapid social change. You might want working families to get a fair deal, but you’re also proud to be a patriotic, often religious American. In short, you’re a populist. And you’re politically homeless.

This is the “silent majority” that actually matters. But Schultz can’t see its members, because their worldview is so far away from the ambient neoliberalism that thrives among big-city cosmopolitans such as himself. Schultz is simply projecting, assuming that voters are dissatisfied with the two-party system for the same reasons he and his fellow elites are. But as Drutman’s research makes clear, there are two kinds of voters who can feel unrepresented by the major parties. The disposition that calls itself “centrist” tends to locate itself in the neoliberal quadrant — even though voters in the populist quadrant are far more numerous and just as underrepresented by the two-party system.

The potential power of the populist quadrant was realized by the victory of Donald Trump. Drutman’s report concluded that the decisive factor that changed between 2012 and 2016 was that Republicans “made gains among the populists.” In 2012, Romney won populists by a 2–1 margin over Obama, but in 2016, Trump won these voters by a 3–1 margin over Clinton. Trump’s personal weaknesses may render him vulnerable with these voters in 2020 — his administration has been filled largely by Reaganites and neoliberals, which is hardly what populists voted for.

Still, any candidate who can effectively occupy the populist quadrant could have an enormous advantage. Not only could such a candidate rely on those voters who identify as populist, but he would also enjoy some crossover appeal. Conversely, a candidate who occupies the neoliberal corner in the lower-right would be at an enormous disadvantage: While a neoliberal candidate could try to appeal to social liberals and economic conservatives, his home quadrant would remain empty. There is no neoliberal base.

Which raises the question: Why do billionaires such as Howard Schultz retain such faith in the neoliberal formula despite the evidence that no voters want to drink it? Why are free markets and social justice the philosophy of choice in Seattle and Palo Alto if this combination is so disliked by everyone else?

The answer can be found in the boardrooms where Howard Schultz made his living. Our era has witnessed an unprecedented groundswell of corporate progressive activism, from boycotts of the NRA to a push to legalize same-sex marriage to the circulation of open letters in support of trans rights and undocumented labor. Corporate leaders are largely white, well-educated, urban, and wealthy, and wokeness, especially to the younger half of that demographic, is a form of social currency. As Ross Douthat has pointed out, such activism is also an adaptive strategy to facilitate continued corporate enrichment: By taking the progressive side in the culture wars, corporations can earn goodwill from the “resistance” and deflect its regulatory impulses.

This dynamic of “woke capital” is active not just with Howard Schultz, but in the neoliberal wing of the Democratic party. Candidates such as Kirsten Gillibrand and Cory Booker use performative wokeness on social issues to hide their pro–Wall Street orientation from the progressive base. For Gillibrand, that means tweeting about intersectionality on the heels of killing derivatives regulation; for Schultz, it means embarking on a media tour to tout a largely symbolic racial-bias training initiative for Starbucks employees.

Political figures whose livelihoods or campaign coffers heavily depend on deregulated markets take it as a given that those markets shouldn’t be toyed with, even as the American population sours on laissez-faire. To make up for that, these figures emphasize social issues. Indeed, Drutman’s report found that the donor class of both parties is more conservative on economics and more liberal on social issues than voters. These elites are likely to feel “homeless” as figures like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders expose the unpopularity of laissez-faire. Yet many make Schultz’s mistake and assume that their frustration is broadly shared.

It’s actually parochial.

It is a travesty that “centrism” is defined in the U.S. as advocacy for a suite of unpopular ideas that are overrepresented in American life. Doubly so when the centrist is a billionaire who says he represents a supposedly “silent majority” of free-market social-justice advocates. The populists, the true silent majority, don’t get to be called “centrists.” They’re either written off as xenophobes or totally ignored. Donald Trump was the first candidate to pay attention to them — and they deserve better. It’s up to populists to demand more effective representation for their fusion of economic fairness and social conservatism. And it’s up to candidates to listen.

To see this article, click read more.

Source: Howard Schultz’s ‘Centrism’ Is a Sham | National Review

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online