By: The Editorial Board – wsj.com – January 20, 2020

When the Montana Legislature created a K-12 scholarship program funded via private donations and tax credits, it was a godsend to Kendra Espinoza. An office assistant by day and janitor by night, the single mom had pulled her two daughters out of public school. One was bullied for studying the Bible during recess.

Ms. Espinoza enrolled them in the nondenominational Stillwater Christian School. “I love that the school teaches the same Christian values that I teach at home,” she later said. But even with financial aid, odd jobs and yard sales, the tuition was “a real financial struggle.” Extra money from Montana’s scholarships, enacted in 2015, could go a long way.

Five years later, Ms. Espinoza is fighting to keep that support. On Wednesday the Supreme Court will hear Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, a case touching on education, religious liberty, and whether 19th-century bigotry still has a place in American law.

The Montana scholarships worked similar to tax-credit programs in many other states. People or companies donated to a private nonprofit fund. In return the state gave them a tax credit, dollar for dollar, up to $150. The money was awarded to families like Ms. Espinoza’s to defray tuition at the schools of their choice.

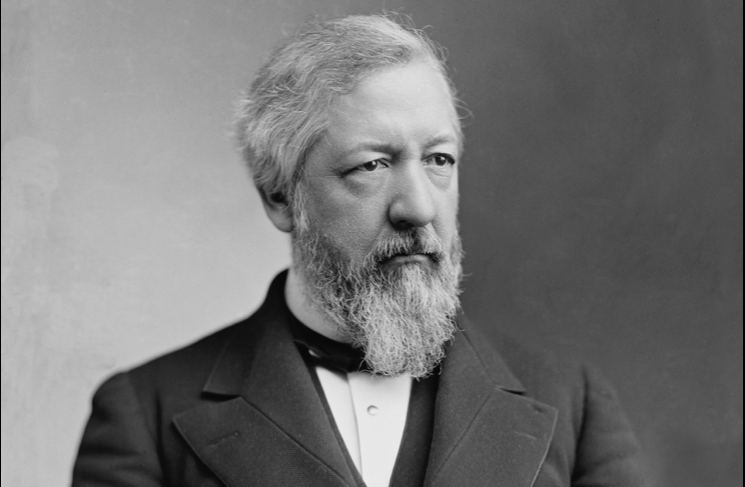

One complication: Montana’s constitution has a clause saying public funds can’t be spent for “any sectarian purpose.” Many states adopted such language in the late 19th century, amid that era’s anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic fervor. These are often called Blaine Amendments, since a federal version was unsuccessfully pushed in 1876 by Congressman James G. Blaine (“the continental liar from the state of Maine,” as his political opponents chanted).

Montana’s Revenue Department issued a rule to exclude the religious from the scholarship program. Secular schools could still get the money, but not Ms. Espinoza and Stillwater. Parents sued with help from the Institute for Justice. In 2018 the state Supreme Court killed the whole program, ruling that the tax credits were indirect state aid to religious schools, in violation of the Blaine Amendment.

Now at the U.S. Supreme Court, the parents argue that Montana’s ruling is unconstitutional under the First Amendment. Free exercise of religion means that if a state passes a neutral program of student aid, it can’t exclude families who pick religious schools. The parents cite Trinity Lutheran v. Comer (2017), in which the Justices held 7-2 that a Missouri ban on sectarian aid couldn’t deny a public grant for playground resurfacing to a religious school.

The parents also say Montana violated the 14th Amendment’s “equal protection of the laws.” Here they give a history of Blaine Amendments. In the 1800s, the public schools reflected a predominant culture: “Teachers led students in daily prayer, sang religious hymns, extolled Protestant ideals, read from the King James Bible, and taught from anti-Catholic textbooks.” When states banned aid to “sectarian” schools, that meant Catholic.

Montana replies that there’s no discrimination, at least not anymore, since the scholarships don’t exist. They were thrown out by the state court, see? Neither the faithful nor the secular are getting the money. This argument seems too clever in its circular logic. If a court strikes down a law explicitly because it includes religious believers, that can’t be unconstitutional since the law was struck down?

The state says its “No-Aid Clause” isn’t anti-Catholic bigotry, but rather a “distinct intellectual tradition.” When Montana wrote a new constitution in 1972, its convention debated and largely readopted the old provision. The goal then, Montana argues, was “protecting religious liberty by creating a structural barrier between religious schools and government.”

Yet the longer history remains. So does the effect: to cast out religious believers from a program enacted in the general interest. Such bias in law requires strict judicial scrutiny.

Given the incrementalism of Chief Justice John Roberts, perhaps it’s too much to hope that the Supreme Court will relegate James G. Blaine to the 1800s where he belongs. In Trinity Lutheran, the Chief’s opinion came with a pregnant footnote, saying it only covered “express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing.” But as the Justices have shown in a long line of cases, religious freedom doesn’t end at the playground blacktop.

To see this article and subscribe to more from WSJ, click read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online