By: Dominic Pino – nationalreview.com –

Both presidential candidates — and their voters — need to face fiscal reality.

Next year is going to be a mess for U.S. fiscal policy. The individual provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the 2017 GOP tax cuts, expire. The suspension of income limits for Obamacare subsidies will end. The spending caps from the 2023 debt-limit deal will go away, and the debt limit will need to be raised again.

State and local governments have until the end of 2024 to decide how they will spend their money from the American Rescue Plan Act. When it runs out, many governors and mayors will ask Washington for more. Contract authority from the 2021 infrastructure law will be running out in 2026, and inflation in the construction sector will cause contractors to raise the alarm that projects will require more funding to be completed.

Debt-funded spending during the pandemic has turned interest payments into the second-largest category of federal expenditures, exceeding military spending and set to continue growing as old debt rolls over in a higher-interest-rate environment. The federal deficit is about $2 trillion right now, 6.3 percent of GDP, in peacetime during an economic expansion with low unemployment. It will be about $2 trillion again next year, and that’s if everything goes reasonably well. The national debt grows by $1 trillion roughly every 200 days.

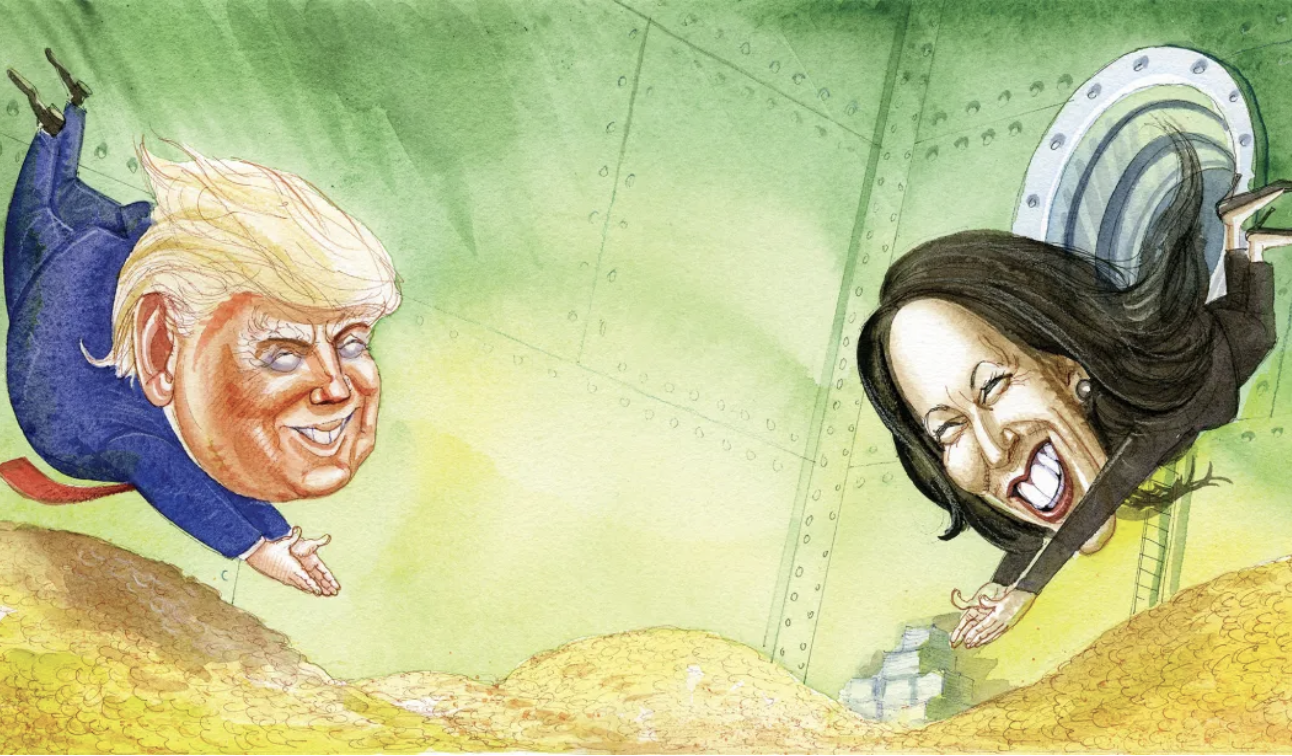

In the ABC debate between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, one of whom will be the president next year, the moderators did not ask a single question about the budget, the debt, or overall tax policy. In fact, the words “budget,” “debt,” and “spending” were never spoken by anyone in the entire debate. The moderators were following the lead of the candidates, neither of whom has any clue how to deal with any of that stuff.

In the short run, the federal budget needs to be restored to some sense of normality after the pandemic-spending blowout. Annualized federal expenditures in the first quarter of 2020 were $4.9 trillion; today, they’re $6.7 trillion. Spending would be expected to be higher today than in 2020 regardless. Still, if it had stayed on its pre-pandemic trend (which was already too high), it would be about a trillion dollars lower.

Both Trump and Harris are partially responsible for that blowout, and they ought to have some ideas on how to clean it up. There’s a case for significant deficit spending during an emergency, but when the emergency is over, it’s supposed to stop. The U.S. ran enormous deficits during World War II, then cut them when the war was won. Even during the recovery from the Great Recession, when government was still spending too much, the deficit was reduced from nearly 10 percent of GDP in 2009 to under 3 percent of GDP by 2015.

For perspective, consider that the deficit this year will be about 6 percent of GDP. During the 1930s, the deficit never exceeded 5.4 percent of GDP. As a share of the U.S. economy, deficits now are greater than they were during the Great Depression, and neither candidate for president is batting an eye.

The difference between then and now is that deficits from here on will be driven by the actuarial tables, not the business cycle or any emergency. Both candidates have agreed that they won’t address the root cause of the debt problem, entitlement programs.

That’s really the whole ball game, in the long run. Over the next 30 years, the Congressional Budget Office projects, Social Security, Medicare, and the borrowing required to fund them will add $124 trillion to the national debt. The rest of the federal budget is roughly balanced over that time horizon.

The $124 trillion is almost certainly an underestimate, because it is based on CBO assumptions that interest rates will never rise above 3.8 percent in the next 30 years. All the extra government borrowing will increase pressure on interest rates. For each percentage point above 3.8 percent, tack on another $40 trillion or so.

The assumption that the rest of the budget will be roughly balanced implies that current law won’t change. That means no recessions, no unforeseen need for increased military spending, and no major new spending programs without concomitant spending cuts. It also means all that stuff that’s scheduled to expire next year and the year after actually does expire, in full, never to return.

And that’s not going to happen. There’s no way of knowing what world affairs will throw at the U.S. over the next three decades, and at least some, if not all, of the policies set to expire will be extended.

Fully extending the TCJA, the largest item, would, depending on the estimate, add between $3 trillion and $5 trillion to the debt over the next ten years. That’s small compared with the impact of entitlements, but it’s still significant. Ideally, the government should cut more than that much in spending, to compensate for the lost revenue and begin to chip away at the spending that is already too high.

It’s not as though elected Republicans have no ideas about cutting spending. The Republican Study Committee has 177 members in the House, and it is chaired by Representative Kevin Hern (Okla.). Its 2024 budget proposal cuts $17 trillion relative to what the government is expected to spend over the next ten years. Republicans wouldn’t even need to get two-thirds of those spending cuts to fully offset TCJA extension. If they could get only half of them, they could extend the tax cuts and still have the largest deficit-reduction bill in U.S. history.

Through budget reconciliation, a special procedure that allows the Senate to bypass the filibuster, Republicans could pass many of those spending cuts with control of the White House, the House majority, and only 51 senators. That’s a possible electoral outcome this November.

Passing such a bill would require strong leadership from the president to sell it to the American people and to ensure that no Republican lawmakers defected. Every spending program in the budget benefits someone, and sometimes “someone” is a Republican. The handful of members who won the tight elections that would give the GOP a House majority are likely to be the least conservative, because they would be elected from swing districts that could flip to the Democrats in only two years’ time.

Holding such a coalition together is really hard work — just ask Mike Johnson or Kevin McCarthy or Paul Ryan or John Boehner. The Senate majority would also be slim. And the entire Democratic Party, mainstream media, and academia would caterwaul about how evil far-right extremists were pushing draconian austerity that would kill the poor, racial minorities, women, children, seniors, the disabled, immigrants, veterans, teachers, firefighters, nurses, and every plant and wild animal in the country.

Of course, all of those things are true no matter what Republicans choose to campaign on. But Trump has chosen to campaign on the barest of agendas. His platform is heavy on unnecessarily capitalized words and light on facts and figures.

Here’s the full plan from Trump’s platform for Social Security: “Social Security is a lifeline for millions of Retirees, yet corrupt politicians have robbed Social Security to fund their pet projects. Republicans will restore Economic Stability to ensure the long-term sustainability of Social Security.”

Here’s the full plan for Medicare: “Republicans will protect Medicare’s finances from being financially crushed by the Democrat plan to add tens of millions of new illegal immigrants to the rolls of Medicare. We vow to strengthen Medicare for future generations.”

Here’s the tax plan: “Republicans will make permanent the provisions of the Trump Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that doubled the standard deduction, expanded the Child Tax Credit, and spurred Economic Growth for all Americans. We will eliminate Taxes on Tips for millions of Restaurant and Hospitality Workers, and pursue additional Tax Cuts.”

The platform includes no mention of the budget deficit or the national debt at all. Rather than preparing for the fiscal fight that is coming in 2025, it leaves Republicans directionless and presents voters with little contrast between Trump and Harris with respect to the budget.

Here’s Harris’s full plan on Social Security and Medicare: “Vice President Harris will protect Social Security and Medicare against relentless attacks from Donald Trump and his extreme allies. She will strengthen Social Security and Medicare for the long haul by making millionaires and billionaires pay their fair share in taxes. She will always fight to ensure that Americans can count on getting the benefits they earned.”

Harris wants to raise taxes on the wealthy. Trump does not. But she has said she would continue Biden’s promise not to raise taxes on anyone making less than $400,000 per year. Allowing the TCJA to expire would raise taxes on basically everyone. Since 98 percent of taxpayers make less than $400,000, Harris is promising 98 percent of what Trump is promising on TCJA extension. She is also promising an expansion of the child tax credit, same as Trump.

After years of easy money and overregulation made housing prices soar, both candidates are talking about housing affordability. Trump wants to “promote homeownership through Tax Incentives and support for first-time buyers, and cut unnecessary Regulations that raise housing costs.” Harris wants, well, basically the same things, but with arbitrary numbers thrown in (3 million houses over four years, $25,000 for first-time buyers).

Where the campaigns diverge is in their economic illiteracy. Trump promises across-the-board tariffs that would be paid by foreigners. (They would be paid by Americans.) Harris promises to lower housing and food prices through prosecution. (If only it were so easy.)

Instead of agreeing on fiscal irresponsibility, maybe Republicans and Democrats could come together on fiscal responsibility. Earlier this year, Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute wrote a report in which he tries to advance that outcome. His plan wouldn’t balance the budget, but it would stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at its current level, around 100 percent, then gradually reduce it to 73 percent over the next 30 years.

He uses realistic assumptions rather than the current-law baseline used by the CBO. In the vein of successful fiscal reforms in Ireland, Sweden, Canada, and other countries, he leads with spending cuts and proposes only modest tax increases. Countries that try to tax their way out of fiscal holes inevitably fail.

Riedl’s plan would change how Social Security benefits are adjusted for inflation, and it would raise the retirement age by three months each year until it reaches 69. His plan would reduce benefits for the wealthy while keeping benefits for the poor. It would not raise the Social Security payroll tax at all.

Medicare, the more budget-busting of the two major entitlement programs, would see a one-percentage-point increase in its payroll-tax rate. That would come with reforms to make Medicare more competitive, as Medicare Part D already is, with a premium-support system for Parts A and B. Higher-income seniors would be expected to pay more of their premiums, but the eligibility age would remain 65.

These ideas aren’t crazy, and capable leaders could sell them to voters. The only reason Social Security still sort of works is that Ronald Reagan and both parties in Congress supported the recommendations of an independent commission to subject benefits to income taxation, something Trump has said he wants to undo. “Today we see an issue that once divided and frightened so many people now uniting us,” Reagan said in his speech on signing the Social Security reforms into law. He did that in 1983 and won 49 states in the election the next year.

That came after Democrats demagogued his earlier proposals to reform Social Security and made it the centerpiece of their campaign against Republicans in the 1982 midterms. They had, in Reagan’s words, “broadcast widely one of the most dishonest canards” by saying that Republicans wanted to cut Social Security benefits.

“Revising the Social Security system has become such a politically lethal issue that most politicians refer to it as the ‘third rail,’” began a story in the New York Times in January 1983. “Third rail” is the term that politicians use even today when talking about Social Security reform. One difference between then and now is that politicians did, eventually, grow up and realize that something had to be done, appointed a commission to figure out what that something was, and then passed it into law. And it would not have happened without the president’s leadership.

Another difference between then and now is that now the problem is much, much worse. It would be one thing if America were fiscally healthy and the candidates wanted to focus their attentions elsewhere. But the budget is a disaster, and really important decisions will need to be made next year. And unlike many of the issues that the candidates have been talking about instead, the government’s budget is completely, 100 percent, absolutely under the control of the government.

That means that whatever crises that come will be completely, 100 percent, absolutely the government’s fault. Government leaders should have the decency to come clean to voters about what’s on the horizon, and voters should demand that they do so. Neither leaders nor voters are fulfilling those responsibilities. And the budget problems are so glaring, so manifestly obvious, that the only way to shirk those responsibilities is to simply never speak of them.

To see this article in its entirety and to subscribe to others like it, please choose to read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online