By: Edward-Isaac Dovere – TheAtlantic.com – February 22, 2020

The phrase Democratic establishment conjures images of something like the Illuminati with the power to determine the outcome of American elections. But so far, the supposedly all-powerful leaders of the party have been about as well organized as The Muppet Show.

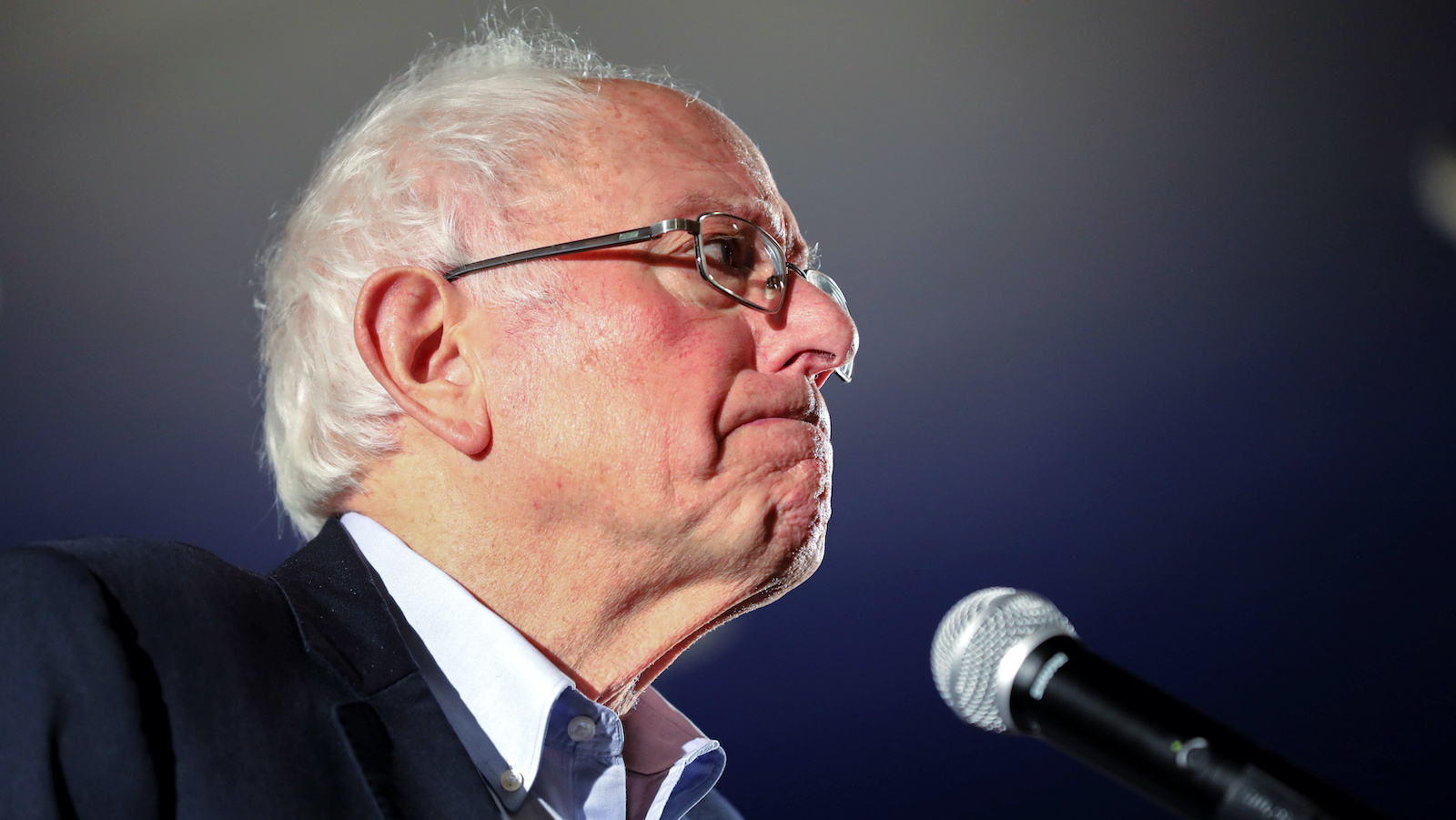

Now, with Senator Bernie Sanders’s massive win in Nevada, he’s taken the lead in delegates and may never lose it. Efforts to stop him so far have been ineffective and made the party seem out of touch. This summer, party leaders may be forced to accept the nomination of a man who’s not officially a member of the party, who won’t have won a majority of primary voters, and whose agenda is popular with his progressive base but doesn’t have as much support with Democrats as a whole.

“The Democratic establishment exists, but like the Republican establishment four years ago, it’s a mess, paralyzed by fear and indecision, and it doesn’t know what to do,” says Matt Bennett, a vice president at Third Way, a moderate think tank that proudly considers itself the home of the establishment. He spoke with me about the candidates faced with decisions about dropping out after today. “The fear is that people will move instantly from ‘I’m not ready [to drop out]’ to ‘It’s too late [to win.]’”

“There’s this misconception that somehow there’s this ‘Democratic leadership’ that decides the candidates,” Eleni Kounalakis, California’s lieutenant governor and a former ambassador to Hungary during the Obama administration, as well as a major party donor, told me this afternoon after watching a big caucus site go for Sanders. Kounalakis, who’s a Pete Buttigieg supporter, had just seen another caucus site go for Sanders. “We don’t have a process to stop a candidate. What he’s running into is a ceiling that’s based on public opinion, not about leadership being against him.”

That hasn’t stopped Sanders from using a supposed party effort against him as a main talking point. Yesterday he tweeted: “I’ve got news for the Republican establishment. I’ve got news for the Democratic establishment. They can’t stop us.”

When Sanders started planning for this race two years ago, he told advisers that he believed the 43 percent of the vote he received against Hillary Clinton in 2016 was a starting point, and he would only gain support this time around. He dismissed suggestions that a significant level of his 2016 success had been driven by antipathy toward Clinton.

Emily’s List, the organization devoted to women’s political empowerment, uses two basic criteria for endorsements—being a woman and being pro-abortion-rights. If Senator Amy Klobuchar or Senator Elizabeth Warren were to drop out, Emily’s List would probably endorse the remaining woman almost immediately, the group’s top leaders have been saying privately. But neither is showing any signs of leaving the race, so the group has so far given $250,000 each to the super PACs supporting them. (Neither candidate even had a super PAC until a week ago, and both had spoken out against the very concept, but both have eagerly taken the financial backing they need to stay in the race.)

“Because they’re both running good campaigns, because they both have a credible path, and because they both would be good presidents,” Christina Reynolds, the vice president of communications at Emily’s List, told me, “we got in this week to support them both.”

Yes, only three states—two of them extremely white—have voted, but versions of this conversation are happening among all sorts of Democratic leaders.

So the remaining candidates leave Nevada all believing that they have a legitimate argument for staying in the race. With no one winning enough support to be considered a strong alternative to Sanders, and with expectations of a contested convention setting in, they’re all sticking around and amassing delegates in hopes of getting another shot at the nomination in Milwaukee in July.

Representative Joaquin Castro of Texas, who came to Nevada to campaign for Warren, says he’d be fine with a scenario in which Democrats enter the summer without a nominee. “Remember, the full primary process includes the convention,” he told me.

Many experienced Democrats worry not just that the party won’t unite and that Sanders will lose to Trump, but that having a democratic socialist at the top of the ticket will squash their hopes of winning new Senate seats, and perhaps even cost them a few existing ones in states like Michigan and Wisconsin. Some worry that they’ll even lose the House majority. They dread the idea of Trump, already clearly feeling unshackled since his impeachment acquittal, feeling even more empowered by winning reelection.

Sanders and his aides argue that he’s the only one who can bring in new voters and win over disaffected Trump supporters. Sanders is actually the way out of the apocalypse, his supporters say. And to those fretting that this is 2016 all over again—with an iconoclastic outsider seizing control of a party—they point out that Trump carried lots of contested Senate seats with him and helped his party keep the House. They add that Democrats who are holding out on Sanders are disconnected from the direction in which younger and nonwhite voters are moving the party.

A cynical, but perhaps realistic, argument has been embedded in Sanders’s campaign from the start: He’s the most electable because he’ll get all the people who would vote against Trump no matter who the Democratic nominee is. But he’s also the only one who will be able to activate an entirely different faction of voters. This assumes that all those anti-Trump voters will turn out for him. But although right now everyone is talking party unity, the Never Sanders whispers can be heard among people who would have called themselves “good Democrats” in any other cycle.

The Sanders campaign is already suspicious of what the party has in store. Nina Turner, a campaign co-chair, expressed skepticism after all the candidates onstage at Wednesday’s debate said they would support whoever the nominee is. “Yeah, that’s what they say,” Turner told me, and went on to repeatedly point out that Sanders campaigned for Clinton after losing to her in the 2016 primary race. “Actions speak louder than words,” she said.

Turner said that if Sanders is the nominee, the party will have to support his agenda on health care, economic policy, and more. “If Senator Sanders wins the primary, he did get the majority,” Turner said. What if he doesn’t get a majority? I asked her. She barely paused. “If he gets 40 and somebody else gets 15, he will get the plurality of it. So we’re going to roll.”

That very well may happen, given that most of the other candidates are still spending more time going after one another than Sanders. Former New York Mayor Bloomberg released a memo on Tuesday calling for everyone else to drop out, then, two days later, former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg put out a memo calling for Bloomberg to drop out.

“Look, I think everybody is going to have to make a decision for themselves about what’s good for the future of the party,” Howard Wolfson, one of Bloomberg’s top advisers, told me. “And I would strongly argue that a divided party in which you have the moderate lane increasingly congested is not good for the future of this party,” he said. Wolfson didn’t mention that it’s Bloomberg who has so far spent half a billion dollars congesting the moderate lane.

Tom Steyer, another Democratic presidential candidate and billionaire, told me that Bloomberg’s flop in Wednesday’s debate was proof of how fluid the race is.

“Stuff happens, and stuff’s going to continue to happen,” Steyer told me. “Are people in it for themselves? Let me be a little more charitable: The people running think that they’re standing for what’s right. And they’re worried that other people, even if they respect them, don’t agree with them and that therefore it could be bad for the country if they’re not the candidate. Is there a selfishness layered on top of that? Probably.”

That is an accusation other campaigns and Democrats would level against Steyer, who is generally treated as an interloper blowing money that he could be spending helping other Democratic efforts. But Steyer has been doing well enough in the polls that many think he could place in the top three in South Carolina. Then again, many thought he’d do that well in Nevada, where he’s projected to finish fifth. Steyer said he’d gladly back down if he thought someone else could take on Trump on the economy and unify the party like he believes he could. He’s doing well among African American voters, he has funded a more significant Super Tuesday operation than most, and he’s got the standing in the polls to show for it. He refuses to be dismissed as the rich guy who should drop out—not while Bloomberg keeps going.

“I don’t even understand that argument. We’ve got people voting for me,” Steyer told me. “I thought that was what we were supposed to be doing.”

If what Steyer and the other candidates are supposed to be doing is beating Bernie Sanders, well, they’re not doing much of that.

To see this article and others from The Atlantic, click read more.

Source: How Bernie Broke the Democratic Establishment – The Atlantic

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online