By: John Fund – nationalreview.com – June 28, 2020

Through retrocession, the capital’s residents could become residents of a new Maryland county named after Douglass.

If ever an issue called out for compromise, it’s finding a way to give the 700,000 Americans who live in the District of Columbia full congressional representation.

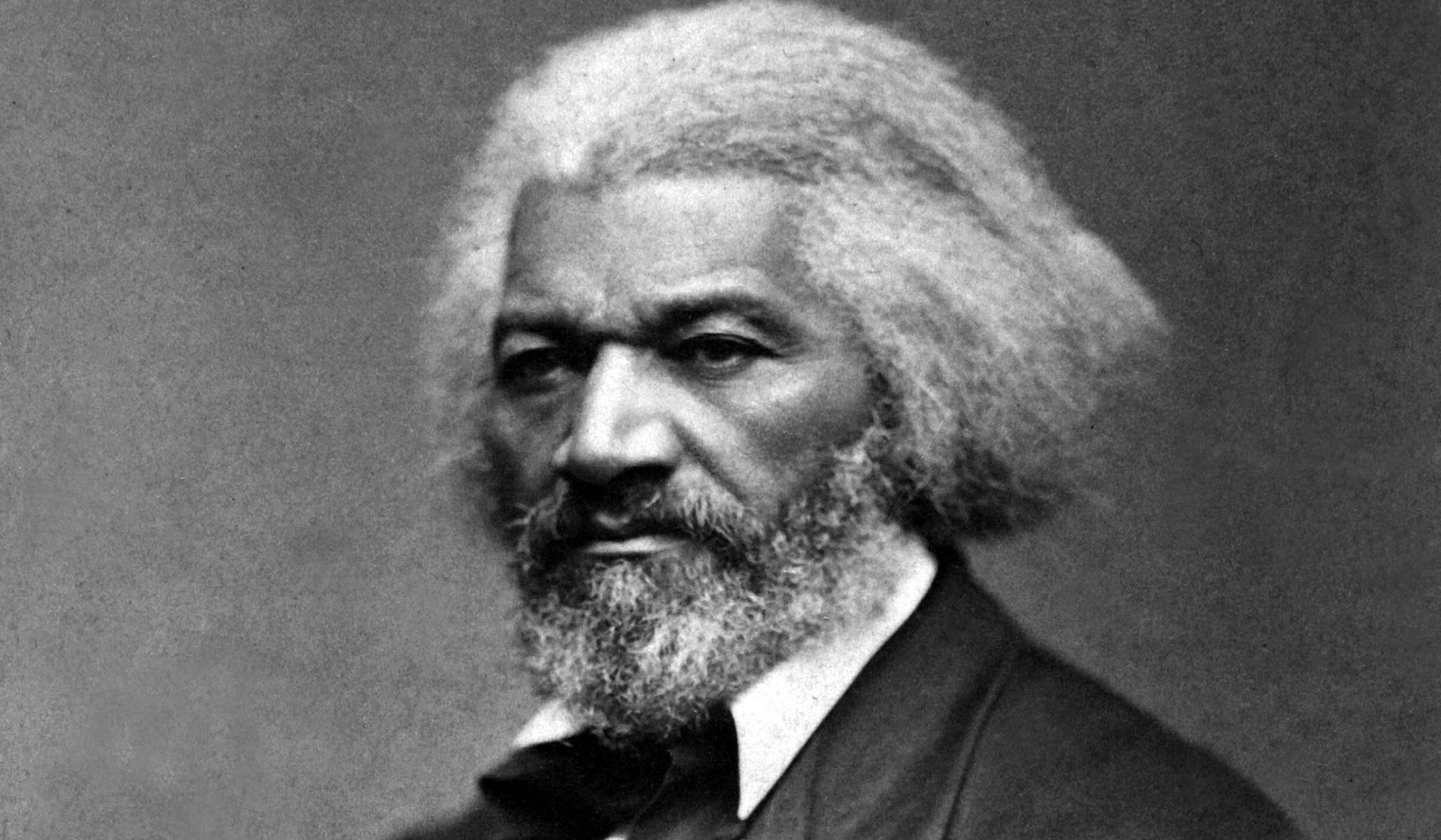

But that’s not what Democrats in the House of Representatives did on Friday when in a lockstep party-line vote they approved creation of a new state of “Washington, Douglass Commonwealth,” in honor of the Virginia-born first president and Frederick Douglass, the Maryland-born abolitionist and former slave. The Senate will now block the measure, and the stalemate will likely continue for years.

There is no doubt that Frederick Douglass thought the 19th-century status of Washington’s residents was unacceptable. Although he himself served as U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia, he noted that its residents have “neither voice nor vote in all the practical politics of the United States. They are hardly to be called citizens of the United States.”

Since then, residents of Washington, D.C., have been granted the right to vote for president and a delegate in the House to represent their interests. But that clearly falls short of full voting rights.

But Washington’s House delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton, the prime mover of statehood, isn’t being honest when she claims that Congress has only two choices: “It can continue to exercise undemocratic, autocratic authority” over the District, or it can pass her statehood bill. No alternative.

But there is an answer that neither continues the unacceptable status quo nor creates an artificial state largely for the expedient purpose of electing two new Democratic senators.

Congress can give back what it took from Maryland and Virginia when it created the District in 1801. It’s called retrocession, and the job is already half done. In 1847, the federal government ceded the portion of D.C. south of the Potomac River back to Virginia. It is now the cities of Alexandria and Arlington. Residents elect a member to the U.S. House, vote for two Senators, and escape the direct federal oversight of their affairs that Washington D.C. endures.

It makes practical sense to simply allow the current residents of Washington, D.C., to become residents in a newly designated Douglass County, Md., and share in that state’s representation in Congress.

Last year, columnist Charles Lane of the Washington Post listed additional advantages of retrocession: District residents would have a large delegation in Maryland’s state legislature, they would regain control of prosecutors and courts, and they could streamline services by eliminating multiple layers of bureaucracy. “The federal government ought to be willing to grease retrocession by supplying transitional aid, possibly by reprogramming annual grants to the District,” he wrote.

In the past, many Marylanders have been knee-jerk opponents of taking back the District. When Maryland Democratic governor William Donald Schaefer said he supported the concept in 1990, an anonymous state senator scoffed at the idea, noting that D.C.’s many urban problems “would greatly strap state resources.”

But the Washington, D.C., of today is booming, gentrification has created a huge tax base, and the city has made progress in lowering crime and creating charter schools. D.C. has a higher per capita personal income than any state does, and a higher bond rating than 35 states.

But the proponents of D.C. statehood act as if the idea of retrocession doesn’t exist. In a Washington Examiner opinion piece in 2018, David Krucoff, a Washington businessman and policy maven, noted his disappointment at how a Senate hearing on D.C. enfranchisement went in 2014:

My disgust with the failure of D.C.’s efforts to gain representation boiled over when I attended a disingenuous Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee hearing on D.C. enfranchisement in September of 2014. At the hearing, Sen. Tom Carper, D-Del., the only senator on the committee who was even present, begged all those testifying from D.C. if there was anything else that could be done besides for D.C. to become the 51st state. Our representatives answered in unison that there was nothing else that could be done.

However, every one of them, starting with the District’s House delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton, knew about the Virginia retrocession. They either avoided the question or lied in their responses right in front of hundreds of us that day.

Since that hearing, Krucoff has tirelessly campaigned for the idea of retrocession. But while many elected officials agree with him privately, none will publicly back it. As Charles Lane noted last year: “It’s revealing that local politicians would resist Krucoff’s proposal (and others like it), even though it accomplishes the main ostensible purpose of the D.C. statehood and voting rights movements.”

I doubt that Frederick Douglass would approve of such short-sighted political expediency and its consequent willingness to let a problem fester rather than solve it.

One of the 19th century’s most eloquent critics of socialism and collectivism, Douglass was a man of decisive action. If given a choice between gaining full voting rights for Washington, D.C., residents (with their new status as residents of his native Maryland) and waiting many more years under the illusion that D.C. statehood will pass political and constitutional muster, we should all ask: What would Frederick Douglass do?

To see this article, others by Mr. Fund, and from National Review, click read more.

Source: D.C. Statehood: What Would Frederick Douglass Do? | National Review

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online