By: Noah Rothman – nationalreview.com – January 2, 2025

In the New Orleans terror attack we saw another example of public officials’ apparent lack of trust that the public can handle the truth.

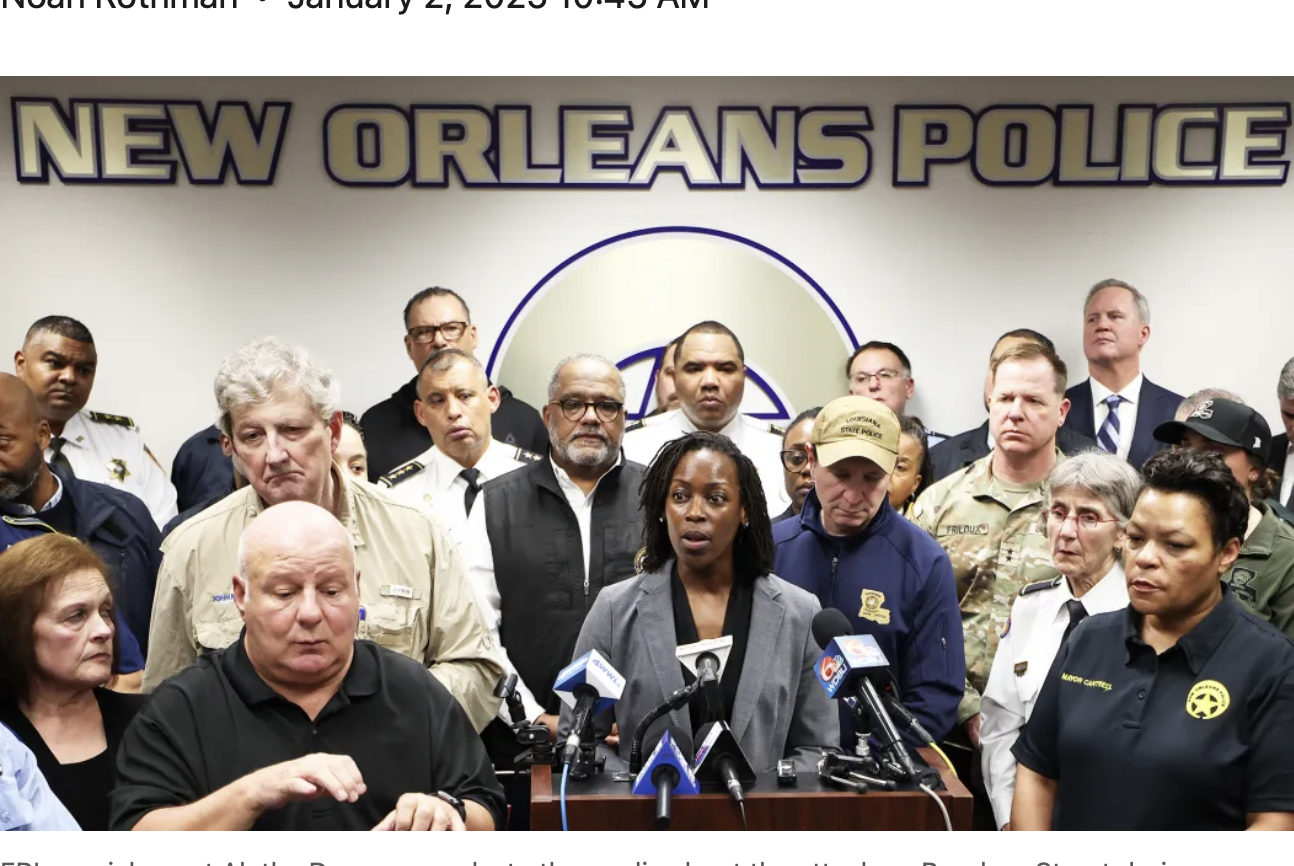

There are a number of perfectly valid explanations for the initial insistence by FBI agent Alethea Duncan that the mass-casualty attack in New Orleans on New Year’s Day was not a terrorist event.

Perhaps Duncan was speaking with undue authority based on her own limited information. Or maybe she was observing the bureau’s definition of what constitutes “an act of terrorism,” as CNN’s Juliette Kayyem speculated, which requires the establishment of motives, including the furtherance of ideological goals through violence, before an act can be deemed a terrorist attack. Possibly. Either way, Duncan’s declarative statement was wholly inaccurate.

In the hours that followed, the FBI determined that this was an act of not just terrorism but radical Islamist terrorism. The suspect, Shamsud-Din Jabbar, was believed to have been acting in concert with other unidentified individuals, some of whom likely helped him construct what police believe were viable explosive devices. Law enforcement cannot rule out operational links between the New Orleans attack and an event that took place almost simultaneously in Las Vegas, where a Tesla Cybertruck exploded outside the Trump International Hotel; the Cybertruck was rented through the same firm that provided Jabbar with the vehicle he used to mow down his targets on Bourbon Street.

At a time when trust in federal law enforcement is on the wane, it’s reasonable to assume that the FBI would do its best to avoid trust-sapping 180-degree reversals like these. Perhaps Duncan’s reflexive dismissal of the obvious implications in this attack is little more than one agent getting out over her skis. But her remarks also fit a pattern in which American public officials seem more inclined to shape public attitudes and behaviors by either withholding information about ongoing crises from citizens or actively misinforming them.

There’s plenty the public already knew — or could have known — about the nature of this particular attack from the outset. We knew that ramming attacks like the one that took place in New Orleans are increasingly common. One took place in Germany just weeks ago, and that event was preceded by similar attacks in France, Wisconsin, and New York City. We knew that the threat level has been elevated since the Hamas October 7 massacre in Israel, and law enforcement has rolled up several sprawling terrorist plots with foreign connections in the intervening months. Despite this record, we also know that law enforcement has not been able to interdict every terroristic plot, as the Mauritanian national who shot “an identifiably orthodox Jewish man walking to synagogue in Chicago” while shouting “Allahu Akbar!” in Chicago last October grimly suggests.

Moreover, we know that the Islamic State has been reconstituting itself — particularly in areas of the world where the West’s influence is limited. “We continue to see a real threat in Iraq and Syria,” Ian J. McCary, the State Department’s deputy special envoy for the global coalition to defeat ISIS, said in March. In addition, “we have seen the emergence of ISIS affiliates — the so-called ISIS Khorasan inside Afghanistan, which poses a clear external threat — and in Sub-Saharan Africa where several ISIS affiliates have emerged.” The situation is particularly bleak in Africa, where “the security situation” has “deteriorated significantly” in recent years. “Approximately 60% of ISIS propaganda comes from sub-Saharan Africa,” McCary observed, “particularly from ISIS affiliates in Nigeria, The Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mozambique.” His remarks provide little confidence that “the fight against ISIS . . . in the information space” is going well.

There are hard calls to make here. Charity and discretion should compel those of good faith to acknowledge the difficulties. In the immediate wake of a terrorist event, does it serve the public interest to provide anxious Americans with unvetted, raw information that could contribute as much to a panic as to enhanced vigilance? The answer isn’t obvious. But the alternative to providing the public with information that may produce undesirable behaviors cannot be the distribution of misinformation designed to manipulate them. Too often, public officials have deferred to the idea that the public needs to be controlled more than informed.

This tendency was on display in the response from public officials to the outbreak of Covid-19. Masking was deemed “not effective in preventing” the virus’s spread, not because that was true but because the government’s priority was to prevent civilians from hoarding masks and limiting hospitals’ access to personal protective equipment, as Dr. Anthony Fauci later admitted. Likewise, he later confessed to simply making up numbers that would constitute the point at which we had achieved “herd immunity” to boost vaccination uptake. “When polls said only about half of all Americans would take a vaccine, I was saying herd immunity would take 70 to 75 percent,” Fauci told New York Times reporters. “Then, when newer surveys said 60 percent or more would take it, I thought, ‘I can nudge this up a bit,’ so I went to 80, 85.” Whatever the altruistic rationale for these deceptions, the damage the public health apparatus has done to the profession’s reputation doesn’t seem to have been worth it.

Other similar mendacities are far less comprehensible. Among them was a claim retailed by “experts” surveyed by the Thomson Reuters Foundation at the height of the Me Too movement that, when it came to protecting and even sanctioning sexual assault and human trafficking, the United States was on par with countries such as Somalia, Pakistan, Yemen, and Nigeria. It was a falsehood that could be propagated only by those who thought the lie a useful tool to promote their ideological project.

We may never know enough about the internal deliberations that culminated in Agent Duncan’s promotion of a falsehood — a deception that could be attributed just as easily to the fog of war as to a sordid impulse to save the public from themselves. But the fact that we cannot rule out the latter, given how frequently American luminaries and public officials resort to promoting manipulative fabrications, is part of the problem.

American institutionalists spend a lot of time thinking about how they might restore the public’s faith in the country’s governing bodies. They should start by displaying the sort of trust in the American public that they expect the Americans to invest in them.

To see this article in its entirety and to subscribe to others like it, please choose to read more.

Source: Don’t Fear the People: Public Officials Don’t Trust the Public | National Review

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online