By: &

Nineteen state attorneys general wrote a letter last month to BlackRock CEO Laurence D. Fink. They warned that BlackRock’s environmental, social and governance investment policies appear to involve “rampant violations” of the sole interest rule, a well-established legal principle. The sole interest rule requires investment fiduciaries to act to maximize financial returns, not to promote social or political objectives. Last week Attorneys General Jeff Landry and Todd Rokita of Louisiana and Indiana, respectively, went further. Each issued a letter warning his state pension board that ESG investing is likely a violation of fiduciary duty.

Mr. Landry’s and Mr. Rokita’s warnings are salvos in a fight numerous states are waging against the ESG policies promoted by the Big Three asset managers—BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street. But they go significantly further in two major respects.

First, Mr. Landry’s guidance spotlights potentially explosive, undisclosed conflicts of interest in the Big Three’s “selective” promotion of ESG criteria against U.S. companies but not Chinese companies. According to Mr. Landry, in 2021 BlackRock exercised its proxy voting rights as Exxon’s second-largest shareholder to lead “an activist campaign that forced Exxon to cut oil production,” without disclosing that many of the “oil fields dropped by Exxon” are “poised to be acquired by PetroChina” and that BlackRock is “one of PetroChina’s largest investors.”

Mr. Landry has a point. BlackRock has an enormous stake in PetroChina, reporting holdings of between one trillion and two trillion shares, representing between 5% and 10% ownership, from 2018-22. If Mr. Landry’s allegations are correct, BlackRock’s ESG-based promotion of oil production cutbacks at Exxon might have been a staggering conflict of interest.

Second, both Mr. Landry’s and Mr. Rokita’s letters are warnings to public pension-plan trustees, who are under the same fiduciary duties that BlackRock is. Mr. Rokita’s opinion concludes that public pension boards are “prohibited” from retaining asset managers who “make investments, set investment strategies, engage with portfolio companies, or exercise voting rights appurtenant to investments based on ESG considerations,” which the Big Three all do.

This conclusion is logical. If BlackRock is violating its fiduciary duty, so is a pension-plan board member or investment staffer who knowingly invests with BlackRock. It’s well-settled law, as the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has stated, that where a “fiduciary was aware of a risk to the fund . . . he may be held liable for failing to investigate” or for not “protecting the fund from that risk.”

By putting pension trustees on notice that the Big Three are “likely” violating their fiduciary duties, Messrs. Landry and Rokita are warning that continued investment with those firms may subject pension board members, staffers and registered investment advisers to personal liability.

The Louisiana and Indiana opinions run counter to new agency rules proposed by the Biden administration that would make it easier for pension fiduciaries to engage in ESG investing. But the proposed federal rules apply only to plans governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. State pension plans aren’t Erisa plans. They are governed by state law, and the fiduciary-duty principles to which Messrs. Landry and Rokita refer are a state-law matter.

Although the letters are tailored to Louisiana and Indiana law, the principles they invoke are part of the common and statutory laws of almost every state. Under those principles, social-impact investing has long been viewed as legally problematic. As stated by the drafters of the Uniform Prudent Investor Act, a model statute that has been substantially adopted by a majority of states, “no form of so-called ‘social investing’ is consistent with the duty of loyalty if the investment activity entails sacrificing the interests of trust beneficiaries . . . in favor of the interests of the persons supposedly benefitted by pursuing the particular social cause.” The letters are therefore a warning to public pension trustees across the U.S.

Until recently, public pension trustees might have had a defense based on the lack of alternatives: not only the Big Three, but every major asset manager in the country has been actively promoting ESG for years. Part of the solution to this problem could be market-based. As reported in these pages, Strive, a new asset-management firm bucking the ESG trend, has emerged, and more will hopefully follow.

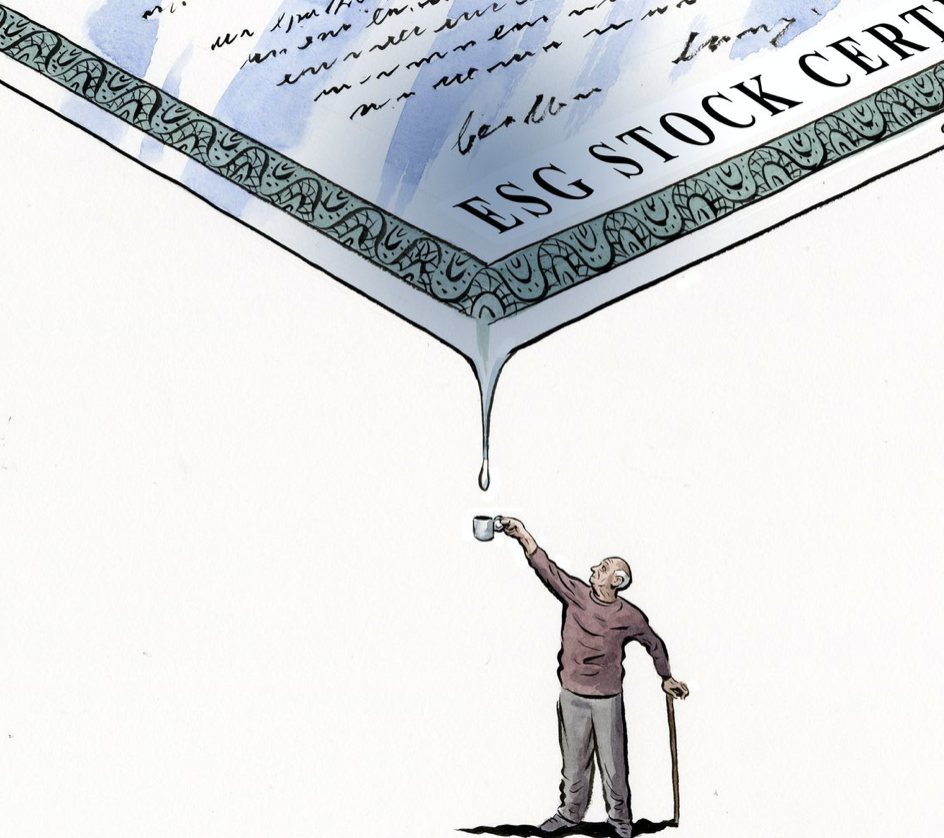

Another defense to ESG investing asserts that ESG factors, though nonpecuniary, are material to profitability and that ESG investing will therefore produce superior outcomes. That claim appears to rest more on hope than fact. A March 2022 report in the Harvard Business Review states that “ESG funds certainly perform poorly in financial terms.” A June 2022 study found that “ESG funds appear to underperform financially relative to other funds within the same asset manager and year, and to charge higher fees,” concluding that ESG asset selection “accounted for an annual drag on returns of -1.45 percentage points.”

The true problem with ESG runs deeper: the unprecedented concentration of wealth accumulated by the Big Three, which now collectively own more than $20 trillion in assets. That’s comparable to the entire annual output of the U.S. economy. The Big Three use their vast economic clout to push a social and political agenda that many Americans don’t support and never voted for. It’s a usurpation of their political rights. But if Mr. Landry and Mr. Rokita are correct, it’s also a legally actionable violation of fiduciary duty—by the Big Three, and by public pension fund trustees who continue to invest with them.

To see this article in its entirety and subscribe to others like it, choose to read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online