By: Ryan Mills – nationalreview.com –

In the summer of 2022, a new restaurant began serving high-quality, but shockingly affordable Mediterranean dishes at a food truck park in San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood.

For as little as $6.99, customers could get bowls of Za’atar chicken, shredded lamb, or chickpea falafel served on beds of rice with sauces and sides, including shredded cabbage slaw, hummus, and roasted sweet potatoes and baby button mushrooms.

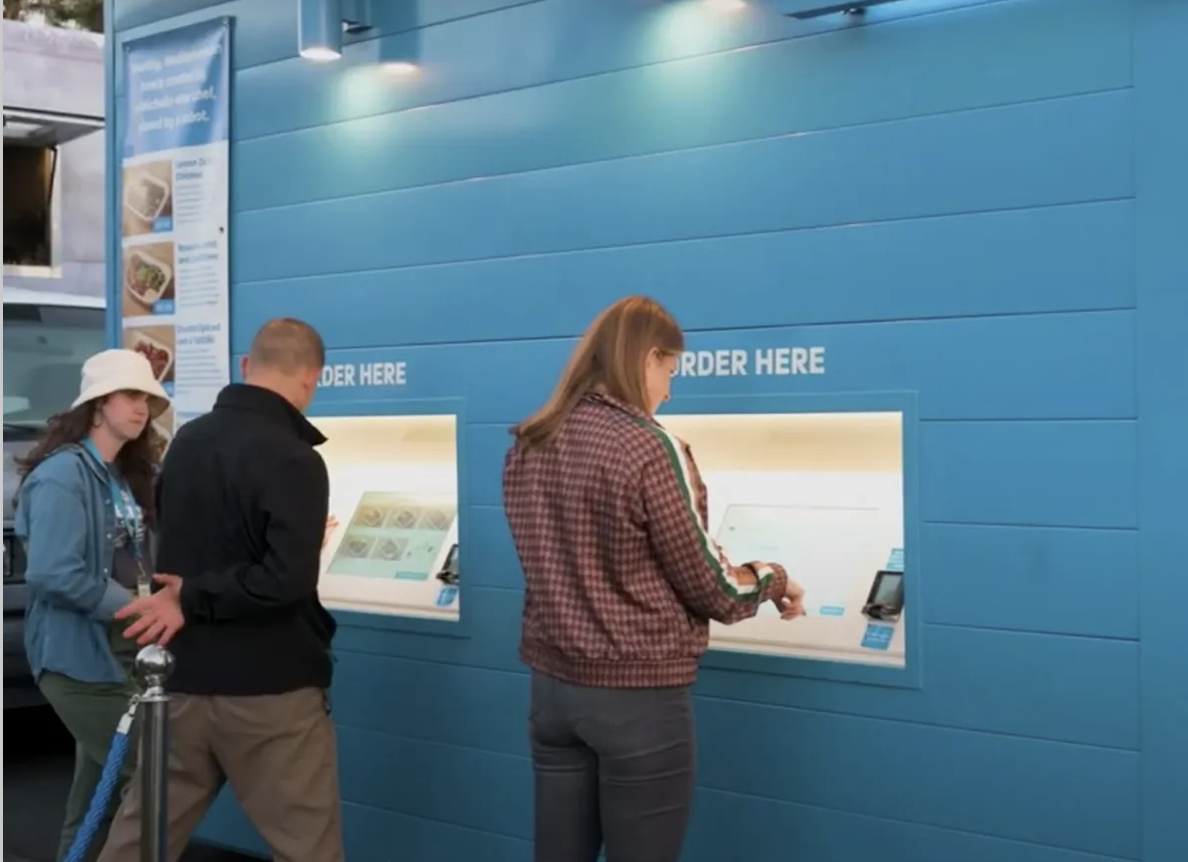

The restaurant, Mezli, was a blue and white pod with ordering kiosks on the front and serving stations on the side. In many ways, Mezli looked like other pod-style restaurants in the park.

But Mezli was different in a key way that allowed it to keep prices so low: It was a robot.

Created by three Stanford grad students, Mezli took orders, assembled bowls, and delivered food and drinks to customers automatically — no humans needed, at least on site.

Each day, a small team, including a chef and cooks, prepped the ingredients in a central kitchen and delivered them to the Mezli robot restaurant, which took over from there.

“The bad news: Artificial Intelligence is going to kill us. The good news: AI can sure serve up some tasty Mediterranean at a beautiful price,” one glowing Yelp review read.

Alex Kolchinski, a Mezli co-founder with a background in software and AI, said the idea for Mezli came amid the realization that rising labor costs are one reason why food prices at area restaurants were climbing so high. He and his friends, who have backgrounds in robotics and engineering, set out to create a modular, mass-producible, and automated restaurant.

He’s described Mezli as what would happen if a vending machine and a restaurant had a baby.

“We realized if you’re doing a bowl-style restaurant, basically assembling stuff from upstream, the only things you have to do is put things in a bowl, whatever the customer orders, put it through an oven to finish cooking the stuff that’s not fully cooked and crisp it up, put some cold ingredients — sauces, toppings — on top, and then serve it to the customer with sides and a drink,” Kolchinski told National Review. “That’s exactly what this machine does.”

“Some people didn’t realize they were being served by a robot,” he added.

Kolchinski and his co-founders eventually wound the experiment down due to a lack of financing. But with restaurant labor costs continuing to rise and eating into already narrow profit margins — particularly in California, which just raised its starting wage for fast-food jobs to $20 an hour under pressure from Big Labor — increasingly sophisticated fast-food robots like Mezli beg the question: are most fast-food jobs necessary at all?

While the fast-food industry was founded on utilizing technology to increase efficiency, the robot revolution seems to be speeding up.

Last year, Sweetgreen, a Los Angeles-based fast-casual salad chain, debuted its fully automated Infinite Kitchen at a restaurant in Illinois. Like Mezli, the Infinite Kitchen moves bowls down a conveyor belt where its system automatically portions out ingredients. The technology is “expected to cut labor costs in half while boosting throughput,” according to a trade magazine.

Similarly, the founder of Chipotle recently launched a new fast-casual chain, Kernel, that utilizes robots to heat and assemble vegetarian meals.

In December, a CaliExpress burger joint opened in Pasadena, complete with robot arms that cook burgers and fries, and AI-powered kiosks that allow customers to order and pay (and tip, of course), with their faces. Leaders at Miso Robotics, one of the companies behind CaliExpress, have said it is the first restaurant where all the ordering and cooking is fully automated.

The robots “don’t call in sick, they don’t get drunk the night before work and come in with a hangover,” one CaliExpress leader told a local TV station. “They’re a little bit more reliable.”

Other restaurants, including Cajun Crack’n in Concord, Calif., are experimenting with robots that can deliver food, bus tables, and may soon be taking orders. Robot bartenders and baristas are also in the works.

While restaurant sales are forecasted to increase this year and the restaurant workforce is expected to grow, owners are continuing to struggle with slim margins, in part due to food inflation and rising labor costs. According to the National Restaurant Association’s 2024 State of the Restaurant Industry report, 98 percent of restaurant operators are struggling with higher labor costs, and 38 percent say they weren’t profitable last year.

Robots are likely part of the solution for many of them. A recent report from the restaurant consulting firm Aaron Allen & Associates found that up to 82 percent of restaurant jobs —mostly in food prep and serving— could be replaced by robots, and that 90 percent of restaurants are considering adding kitchen-automation tech while the cost is dropping.

With labor costs up and tech costs down, “we can expect restaurant robotics to boom over the next few years,” the report concluded.

“The tide has turned, this is no longer a question of are robotics coming to the industry,” Jake Brewer, Miso Robotics’ chief strategy officer, told CNBC last year. “It’s a foregone conclusion. The question is at what pace and in what form.”

Kerry Jackson, a fellow with the Pacific Research Institute in California who writes about robots and the minimum wage, suspects the $20 minimum wage will hasten the robot revolution.

“Laws like this, policies like this, just don’t leave too many options for businesspeople,” he said. “They’re not charities. They’re not here to make sure everybody has a living wage. They are not fountains of wealth that can be tapped into at any time.”

California fast-food operators who spoke to National Review before and after the $20 minimum wage took effect said they care about their workers, treat them like family members, and will try to avoid cutting back on staffing because of the wage hike.

“At the end of the day, we can’t be a vending machine,” Harris Liu, a Sacramento-based McDonald’s franchisee told National Review earlier this month.

But some fast-food franchise owners have already started slimming down their operations.

Studies have shown that the increased use of robotics does significantly impact jobs and earnings. In 2020, for example, MIT researchers found that for every robot added per 1,000 U.S. workers, wages dropped by 0.42 percent and the employment-to-population ratio dropped by 0.2 percentage points. That has resulted in a net loss of about 400,000 jobs, they found.

A 2017 study by economists with the University of California Irvine and London School of Economics, which looked at 35 years of government census data, found that automation disproportionately affected low-skilled workers who are old, young, female, and black.

Djarae Lucas, the lead organizer with ROC the Bay, a far-left food-service workers’ rights organization, fretted in an interview with a Bay Area CBS station that robots could decimate restaurant jobs. ROC the Bay did not respond to an interview request from National Review.

“I think a lot of people see food service as an easy, simple job you only do once but, for a lot of us, it’s a way of life,” Lucas told CBS News Bay Area.

A recent report in Fortune found that in its early stages, fast-food robots aren’t replacing workers, but are instead making their jobs more enjoyable and less repetitive, freeing them up to provide a human touch that robots just can’t. At CaliExpress, for example, humans still pack the food. Even at Mezli, they were required to have a staff member on hand for regulatory reasons. That person greeted customers and helped them with the process.

It’s unclear how long that balance will last, however, as automation is entrenched, the technological kinks are worked out, and employee costs rise.

“If you can replace an employee who takes breaks and might join a union and has to have vacation time with a piece of machinery that doesn’t need breaks, that doesn’t join a union, once you’ve paid for it you’ve paid for it, I would do that if I were in business,” Jackson said.

Proponents of fast-food robots — and robots generally — argue that they will help to cut back or eliminate mindless, repetitive tasks, freeing humans up for more satisfying work. Jackson agrees that robots could open to the door to better jobs for people.

“A good economy will churn out better jobs, if you let it,” he said.

But for many people, particularly young people and people with limited skillsets, entry-level jobs in retail and fast-food have historically been important stepping stones. Robots will likely make many of those low-skill economic entry points obsolete.

“It’s not easy for somebody who does not . . . have the skills or maybe not have the language to go right from being a line cook at McDonald’s to say, ‘I’m going to design robotics,’” said Jackson, who pointed blame at policy-makers for mandating an artificially high minimum wage. “They’re not afraid to mandate anything out there that they think will help them politically.”

Kolchinski said he and his colleagues didn’t get a lot of pushback from people suggesting that Mezli, and the technology behind it, could lead to people losing restaurant jobs. For people who did mention it, it was typically a second-degree concern, he said.

Kolchinski said he sees restaurant robotics as a solution for an industry “screaming for help” amid a worker shortage. The stereotype of teenagers starting out their working lives with after-school jobs in fast-food restaurants appears to be changing, he said.

“My sense of it,” he said, “is people just aren’t that excited about doing this line of work anymore.”

Kolchinski said he and his Mezli cofounders, Max Perham and Alex Gruebele, eventually ran out of money and dissolved the company last year. In a difficult capital landscape, Mezli ended up in something of a financial “dead zone,”Kolchinski said.

He said he learned that working with hardware, rather than software, is operationally intensive, and a “very, very, very hard thing to do.” And it requires money — a lot of it.

“If the investors aren’t excited enough about the potential returns, or they’re scared by the complexity of it and the many risks of it, which are real, then you’re maybe not going to raise enough money to make the thing go,” Kolchinski said of Mezli’s fate.

Kolchinski said he suspects that in the coming years, robots and restaurant automation will be rolled out piecemeal by existing chains, not by new companies like Mezli.

“They’re the ones with the locations, they’re the ones with access to a lot of capital,” he said. “So, it feels like maybe not the best place for a startup to be playing right now.”

In Mezli’s wake, Kolchinski is pursuing new startup projects in the software field, though he said he still likes the food-service space. And he remains proud of the technical success he and his Mezli cofounders and colleagues had.

“The technology did work,” he said. “The product did work, and the people did like it a lot.”

To see this article in its entirety and to subscribe to others like it, please choose to read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online