By: Merrill Matthews – ipi.org – October 2, 2018

Synopsis:

The health insurance system has failed America. Most of the blame lies with state and especially federal government intervention. Lawmakers have increasingly abandoned long-standing actuarial principles, culminating in the Affordable Care Act. The result is insurers are increasingly covering small and routine health expenditures and exposing patients to very expensive costs, turning the principle of health insurance upside down. Short of repealing Obamacare, Congress should give insurers enough flexibility to operate outside of the current restrictions.

Introduction:

The health insurance system has failed America. While health insurers played a role in that failure, most of the blame lies with federal and state government intervention and micromanagement—and arguably mismanagement. In essence, the more federal and state politicians and bureaucrats tried to improve access to quality, affordable health insurance, the less access people had—with the final blow coming from President Obama’s misnamed Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Can the health insurance system be fixed? Maybe, but only if politicians are willing to let it function like real insurance rather than using it as a social justice tool to achieve their vision of “fairness”—and their chances of reelection.

How Insurance Is Supposed to Work—and Why

The principle behind any type of insurance is simple: People or businesses face a risk and want to avoid the full cost of that risk if it occurs. So, for example, individuals who want to limit the financial risk of death may buy life insurance. Those who want to reduce the risk of financial loss if their homes are robbed or destroyed buy property insurance.

In each case the applicant applies for coverage and the insurer assesses the risk the applicant brings to the insurance pool and charges a premium based on that risk—or declines to offer coverage if the risk is too high.

That’s why young people, who have a lower statistical risk of death, will typically have a lower life insurance premium than older people. On the other hand, older adults may face lower auto insurance premiums than younger people, especially males, who tend to be more aggressive drivers.

Underwriting insurance policies has been a very successful model backed by centuries of experience. Insurers’ ability to decline coverage or charge high-risk applicants more encourages individuals and companies to enter the insurance pool before an unforeseen incident occurs and avoid risky behaviors, both of which are essential for a stable insurance market.

Why Health Insurance No Longer Works

Most insurance markets—life, property, auto, etc.—still rely on standard actuarial principles. Not health insurance.

While health insurance pre-dated World War II, it began expanding during the war when employers, who couldn’t boost wages because of wage and price controls, began offering health coverage to attract good workers. That expansion gained momentum when the IRS ruled in 1943 that employer spending on coverage would be tax-free to the employee—a “tax exclusion” because the money spent on coverage is excluded from income.

That coverage was essentially hospital coverage, which represented the primary financial risk in health care. But because employer-provided health insurance is excluded from personal income tax, and because workers (incorrectly) believe the cost of coverage comes out of the employers’ pocket rather than their own, workers and their unions wanted more of it. The result is, over time, employer-provided coverage became more and more comprehensive, increasingly insulating employees from the cost of care.

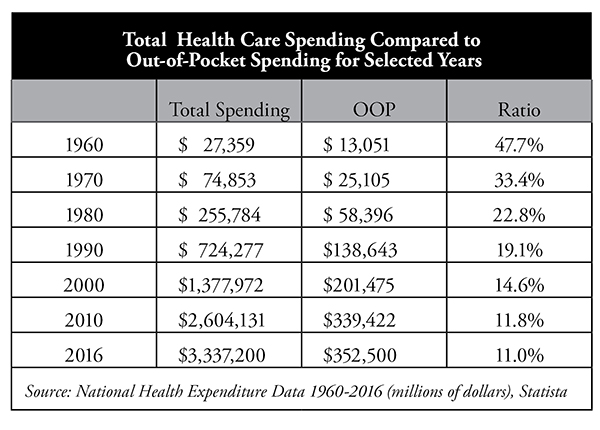

As the table shows, in 1960 patients paid nearly 48 percent of all health care spending out of pocket (OOP). By 2016, total out-of-pocket spending had declined to about 11 percent. However, after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014, with its very high (and growing higher) deductibles—especially for bronze-level plans—and other coverage changes, out-of-pocket spending is likely to rise again.

That decades-long trend toward lower OOP spending fundamentally changed the nature of health insurance and the way people consume health care. Patients simply had little reason to worry about health care prices or how much they were spending.

The Government Gets Involved

Historically, insurance was regulated at the state level, yet states initially refrained from imposing a heavy thumb on health insurance. However, over time patients and providers representing a wide range of medical conditions and services began lobbying their state elected officials to cover their special interests. The effort worked.

States increasingly began to mandate that health insurance cover specific providers or medical conditions. That list of mandates grew from a handful in the 1960s to 2,271 by 2012, the last year the Council for Affordable Health Insurance published its state mandate tracker.1

Those mandates covered all types of providers and services from the most important to the marginal. For example, three states required the coverage of “oriental medicine,” two states mandated “port wine stain elimination,” three covered “athletic trainers,” and four “naturopaths.” Thirty-four states required the coverage of “drug abuse treatment,” even for teetotalers.

While there is nothing wrong with patients wanting or using these services, insurers typically did not cover them. State governments forced them to do so, which began pushing up the cost of health insurance and creating an unintended problem: increasingly unaffordable coverage.

However, even as the states were increasing their regulatory efforts, the federal government largely steered clear of health insurance regulation. The Employee Retirement and Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) gave the federal government some say in the regulation of employer-provided health insurance. Importantly, ERISA also allowed large employers that self-insure—i.e., the employer rather than insurers bears the claims risk—to avoid nearly all state-imposed health insurance regulations.

Everything began to change when President Bill Clinton tried to pass comprehensive health care reform in 1993, referred to as ClintonCare. The legislation failed, but the effort opened the door for Congress to become increasingly involved in health insurance. In 1996 Congress passed its own federal health insurance mandate: the Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act, which restricted health insurers from limiting how long a mother having just given birth could stay in a hospital.

Congress also passed in 1996 the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which imposed numerous restrictions on health insurance, established certain privacy practices and created Medical Savings Accounts (the forerunner of Health Savings Accounts).

In short, the gate for federal health insurance regulation was pushed wide open. By the time President Obama and Democrats began drafting the Affordable Care Act, Democrats in Congress not only considered it appropriate to micromanage the health insurance system, they saw it as imperative.

Perverse Economic Incentives Drive the System

[ . . . ]

Obamacare Doubles Down on Bad Economic Incentives

[ . . . ]

Health Insurers Limit Care

[ . . . ]

Insurers Restructure Coverage Options

[ . . . ]

Attracting the Healthy

[ . . . ]

The Height of Hypocrisy

[ . . . ]

Health Insurance That Is No Longer Insurance

[ . . . ]

Is There a Solution?

[ . . . ]

Conclusion

[ . . . ]

To see this article, click read more.

Source: How Health Insurance Failed America > IPI Issues > Institute for Policy Innovation

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online