Of all the bizarre aspects of the 2016 presidential campaign, none has been more puzzling to many observers than the embrace of Donald Trump by evangelical Christians. After losing the evangelical vote (and first-in-the-nation caucuses) to Ted Cruz in Iowa, Mr. Trump won a plurality of evangelical votes in a string of primaries. He did so again in Michigan and Mississippi this week, and a Fox News poll shows him with a 17-point lead among evangelicals ahead of the March 15 Florida primary. Mr. Trump would not be the Republican front-runner today without his ability to compete for evangelical votes.

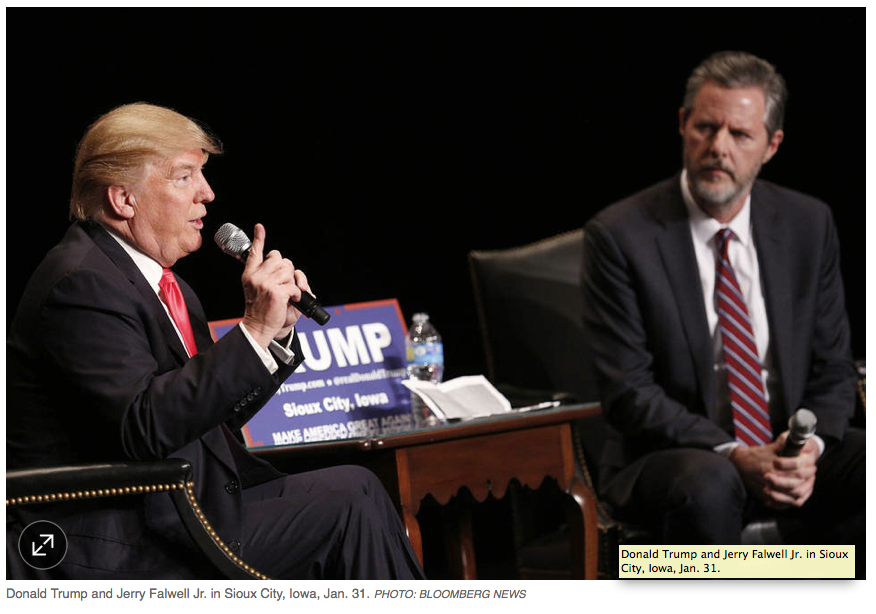

The vision of Jerry Falwell Jr. and Sarah Palin endorsing the twice-divorced Manhattan real-estate developer while evangelicals pack arenas to cheer his unique brand of politics-as-performance-art has caused some jaws to drop. For the chattering class, the odd alliance is like a plot twist from “Elmer Gantry,” offering an irresistible opportunity to bash the Republican front-runner and the party’s evangelical base.

New York Times columnist Frank Bruni recently faulted evangelicals for supporting a man who “personifies greed” and “radiates lust,” proving “how selective and incoherent the religiosity of many in the [Republican] party’s God squad is.”

This consternation is shared by more than a few evangelicals. Former George W. Bush White House aide Pete Wehner has bemoaned his coreligionists’ joining Mr. Trump in an angry politics of grievance that seeks “scapegoats to explain their growing impotence.” Southern Baptist leader Russell Moore offered a simpler, half-in-jest explanation in a Washington Post op-ed: Many evangelicals “may well be drunk right now.”

But something larger and more interesting than resentment (or spirituous liquor) explains Mr. Trump’s performance among evangelicals.

First, a reality check: Mr. Trump is currently winning about one-third of evangelicals—about the same share of self-identified evangelicals who supported the primary campaigns of Sen. John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012. An impressive performance for Mr. Trump in a crowded field, to be sure, but hardly a majority. If the race narrows to Messrs. Trump and Cruz, expect a fierce, neck-and-neck battle for voters of faith.

Mr. Trump benefits from an issue mix custom-made for an outsider businessman promising toughness on the international stage. After the Great Recession of 2008 and the terror attacks in Paris and San Bernardino late last year, Americans desire a strong leader who will revive the economy and protect the homeland. This is true for evangelicals too.

Despite what liberal pundits imagine, they don’t vote solely based on abortion and gay rights. A February Quinnipiac University survey found that the top issues for evangelical voters in the Republican primary were the economy (26%), terrorism (21%) and immigration (9%). Only 6% listed abortion.

Second, evangelicals don’t cast ballots based only on a candidate’s religiosity (or lack thereof). They backed Ronald Reagan, a former Hollywood actor and the first divorced man to occupy the White House, over Southern Baptist Jimmy Carter. Reagan, while he was a deeply spiritual man, rarely attended church and eschewed the label “born again.” But evangelicals admired him because he was pro-life and cast the Cold War in starkly moral terms. Those stands trumped Mr. Carter’s piety.

Similarly, Mr. Romney, a devout Mormon, drew 78% of evangelicals’ votes in the 2012 election, despite their profound disagreement on theology.

Some view this political eclecticism as spiritual dissonance. The media lacerated Mr. Trump for mangling a quote from “2 Corinthians” and referring to Holy Communion as “the little cracker.” But evangelicals are less judgmental than the common stereotype suggests. They also take seriously the Constitution’s prohibition on a religious test to serve in government, in part because it could someday be used to exclude them. This is a sign of civic health, not hypocrisy.

The deepest crack running through the GOP electorate shaping Mr. Trump’s constituency may be class, not religion. Journalist Ron Brownstein, writing in the Atlantic magazine in February, showed that Mr. Trump’s strongest support comes from white voters without a four-year college degree, especially blue-collar evangelicals. Mr. Trump speaks to their economic anxiety when pledging to bring jobs back to the U.S. and stop illegal immigration.

Yet Mr. Trump’s message is not about bread alone. He has condemned the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision last year on same-sex marriage, saying the matter should be left to the states. Mr. Trump professes to be pro-life. In a recent interview with the Christian Broadcasting Network, he vowed to repeal the prohibition on political speech by pastors and churches that has threatened their tax-exempt status and led to IRS harassment.

Rather than condemn Mr. Trump’s evangelical supporters as bigots or the Bible-toting booboisie, we would do better to understand what animates them. Are they disillusioned by Republicans promising to appoint judicial conservatives to the Supreme Court, only to see a Republican-appointed majority on the court uphold Roe v. Wade and redefine marriage? Are they tired of a party that seeks their votes but often treats their concerns as a liability? Perhaps. Evangelicals are not immune to the sense of betrayal by party elites that prevails at the grass roots.

Mr. Trump may not worship at the same church or share the theology of most evangelicals. But he is a voice and vehicle for the disenchantment they feel toward Washington, and their yearning for a strong leader to transform it. Republicans would be wise to figure out how to harness this force in a positive—and winning—direction before it runs them over.

Mr. Reed is founder and chairman of the Faith & Freedom Coalition.

Source: Ralph Reed, www.wsj.com

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online