By: Kyle Smith – nationalreview.com – January 28, 2020

A superb documentary delivers a measure of justice to an extraordinary justice.

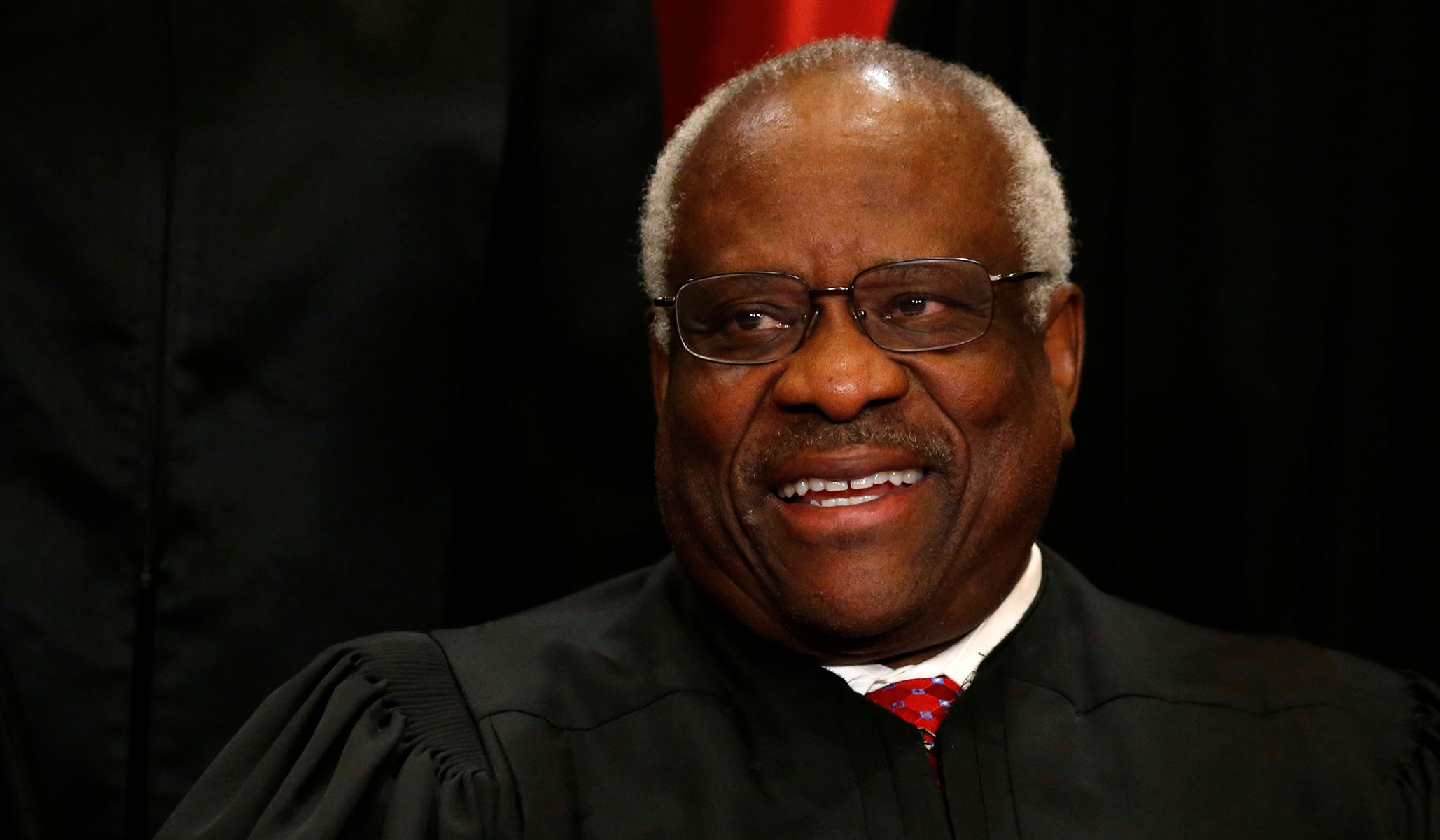

Among the most prominent figures in American politics, perhaps none is as poorly understood as Justice Clarence Thomas. Watching him tell his riveting story at length on camera for the first time, it becomes evident that the man has been deeply wronged — maligned, disparaged, written off.

Thomas may be the most famously silent public figure since Calvin Coolidge. But he has much to say in Michael Pack’s excellent documentary Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words, a measure of long-delayed redress for Thomas’s reputation. Should Thomas remain on the high court until his 80th birthday, as has become common, he would become the longest-serving justice in U.S. history. May he have that last laugh.

Until then, this film should serve as a standard introduction to Thomas and what he has overcome. He reminisces about his poverty-scarred childhood in Georgia, his time preparing to be a priest, his disillusionment following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and his subsequent undergraduate turn to radicalism in the Black Power era. The story of how he became one of the most important conservative thinkers in American history doesn’t fit any path or pattern. Thomas is his own man. He blazed his own trail.

Born in 1948, Thomas knew poverty of a kind we can barely imagine today. He didn’t know his father. In his Savannah neighborhood, toilets flushed into open ditches behind people’s homes. His mother, a maid, couldn’t support him or his brother Myers, so one day the two of them were told to pack up their belongings and go live with their grandparents, Myers and Christine Anderson. Thomas recalls that everything either boy owned could fit in a single brown paper bag — “and neither bag was full.” His grandfather’s welcome consisted of the following words: “Boys, the damn vacation is over.”

Young Clarence and Myers would be expected to toil “from sun to sun” but Myers Anderson was relatively affluent thanks to his job (on which the kids joined him every day after school) delivering fuel oil by truck. Thomas adapted quickly to his grandfather’s ways and his directive, “You can give out, but you can’t give up” would later serve him well. So insistent was Myers Anderson that his grandchildren not shirk any duties that he told them if they died, he would watch their bodies for three days to make sure they weren’t faking.

In Catholic seminary, where there were virtually no other blacks around, a priest told Thomas he would never go far if he didn’t shed his dialect and learn standard English, so he mastered proper speech. Part of his determination was fueled by awareness of racism: “You assume you’re going to be discriminated against,” Thomas says in the film. “So I can’t get a 98. . . . I have to have 100. In other words, to leave them nothing but race. It’s sort of like check, mate.” Thomas dropped out of school after Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered and a student said he was glad about it. His grandfather was furious and ordered him out of the house: “Today. This day.”

But Thomas won admission to Holy Cross, where he broke with everything he’d believed. “I thought he was weak,” he says about his grandfather. The old man didn’t realize he’d been duped into playing along in the white-power structure. Young Thomas knew better and became a student protester. It was during one mob demonstration that he happened to wander into a church, where he prayed for direction. “If you take anger out of my heart, I’ll never hate again,” he promised God. At Yale Law School, he took up libertarianism, then found a job with Missouri politician Jack Danforth, then the state’s attorney general and later a Republican senator. Thomas rose fast, beginning his first judgeship in 1990 and earning a tumultuous Supreme Court nomination the following year, aged only 43.

By this point, Thomas was once again the man his grandfather had built: “I’d rather die than withdraw,” he declared after Anita Hill, a former colleague, accused him of pestering her for dates and making two dirty jokes that instantly became notorious. She offered no corroboration for her claims — no one else had heard her make them — and had no answer when asked why she had followed Thomas from one job to another. Many other female coworkers came to Thomas’s defense. Surveys showed the public believed Thomas by a margin of more than two to one. But the media decided to define Thomas by Hill’s unsupported allegations. Cartoonists portrayed him as undeserving, a shoeshine boy, a Klansman. Frankly racist imagery is acceptable when used against a black conservative.

The movie tells a story that has been a long time coming; Thomas created a certain mystery or void with his trademark silence: He once went ten years without asking a question during oral arguments. The implied explanation for this is, to those aware of his erudition and his welcoming personality, completely false. Thomas is anything but sullen. Rather, he simply feels it is not the place of a justice to insert himself into the arguments. Indeed, in nearly any other court, it would be highly unusual for a judge to argue with the lawyers. “The referee in the game,” says Thomas, “should not be a participant in the game.” Clear enough.

To see this article, others by Mr. Smith, and from National Review, click read more.

Source: Clarence Thomas Documentary Corrects the Record on Unjustly Wronged Man | National Review

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online