By: Ben Sasse – wsj.com – October 12 2018

The Supreme Court confirmation process for Brett Kavanaugh didn’t fully break the nation, but it did prompt more Americans to wonder if that moment is approaching. It’s been a while in coming. Over the past year, I’ve heard thousands of my Nebraska constituents and dozens of my colleagues in the Senate, of both parties, say roughly the same thing: “It feels like we’re at a tipping point, and X or Y might be the final, make-or-break battle.”

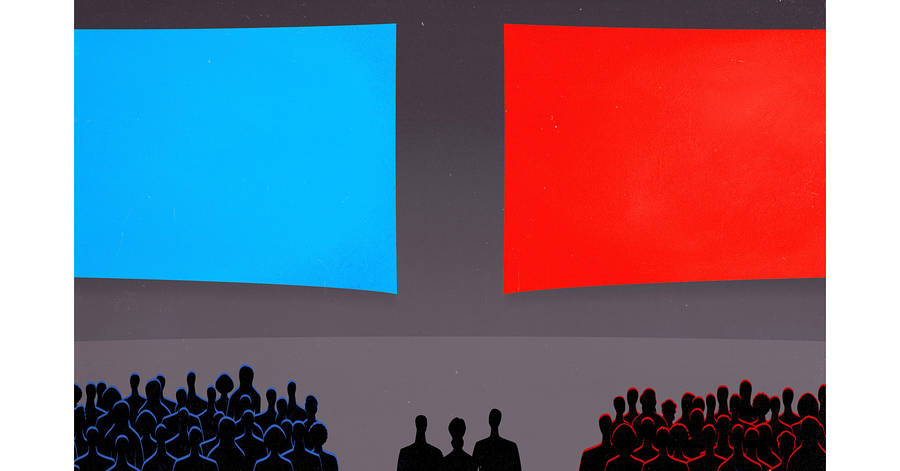

More Republicans and Democrats are placing politics at the center of their lives. Both sides seem to believe that a grand solution to our political dysfunction can be found inside politics. If only we could vanquish those evil people waving a different banner, this thinking goes, we’d be on the road to national recovery.

But nothing that happens in Washington is going to fix what’s wrong with America. It’s not that our battles over the Supreme Court, over dignity for accuser and accused alike, over issues like taxes and regulation and immigration don’t matter. They matter a lot. The problem is that our ever more ferocious political tribalism and mutual hatred don’t originate in politics, so politics isn’t going to heal them.

Humans are social, relational beings. We want and need to be in tribes. In our time, however, all of the traditional tribes that have sustained humans for millennia are simultaneously in collapse. Family, enduring friendship, meaningful shared work, local communities of worship—all have grown ever thinner. We are creating thicker, more vehement tribes around our political differences, I believe, because there is a growing vacuum at the heart of our shared (or increasingly, not so shared) everyday lives.

Loneliness is everywhere in the U.S., across every sector of society. A survey of more than 20,000 American adults conducted earlier this year by the health insurer Cigna and the market research firm Ipsos found that a majority of us are lonely, based on responses to the UCLA Loneliness Scale. The highest scores were reported by the youngest adults, ages 18 to 22. The researchers describe it as a “loneliness epidemic.”

None of this should surprise us. Americans today have fewer shared projects than our parents and grandparents did, and we belong to fewer civic groups. Because we change jobs more often, we have fewer lasting work friendships. We delay marriage, have fewer children and live in larger homes, more separate from those of our neighbors. We move from place to place for relationships, economic opportunity and better weather—and we end up with economic opportunity and better weather.

The Harvard social scientist Robert Putnam chronicled the collapse of associational, neighborly America in his book “Bowling Alone” (2000). In the nearly two decades since, the smartphone has further undermined any sense of place by allowing us to mentally “escape” our homes and neighborhoods. We can instantly connect with the supposedly more exciting lives of others. These moments add up, until we’re in an almost permanent state of dissociation, punctuated only by the most urgent demands of life, to which we tend halfheartedly.

None of us wants to be left out. The same isolation we felt at the edge of the cafeteria or as the last kid picked for kickball causes everyone to yearn for a group. Even though political ideology is a thin basis for intimate connections, at least our cable news tribes offer the common experience of getting to hate people together. As relational nomads, it’s far easier now to be together against something than for something. It’s not as fulfilling, but at least we’re not totally alone.

Americans have always had political disagreements with their neighbors, but in the past, political differences could disappear when Friday night ballgames rolled around and the whole town turned out wearing the same colors and cheering for the same team. Today our towns are hollower, and we’re not on the same team anymore.

Though it’s tempting to think that the sorry state of our public square has to do with fights over hot-button policy issues and the president’s latest tweet, the problem runs deeper than that, in ways that aren’t always personally comfortable. A big part of the problem is the habits and attitudes of elites.

By “elites,” I mean just about everyone reading this—the mobile, educated class. Prof. Putnam defines the elite as people with at least one parent who graduated from college, which puts them in the top socioeconomic third of society. In the U.S., there is a growing divide—in family structure, educational achievement and economic prospects—between this top third and the bottom two-thirds. More than ever before, we are retreating into silos that separate us from people who don’t share our socioeconomic background.

The social scientist Richard Florida of the University of Toronto insightfully segments the U.S. into three categories of people: the mobile, the rooted and the stuck. The mobile are those who can afford to move to areas with more opportunity; the rooted are those who have the means to move but choose to stay; and the stuck are those who lack the resources to make any real choice.

In the U.S., the mobile and the stuck categories are growing, while the rooted are rapidly dwindling. Place is being undermined by the digital revolution, and all of us, wherever we fall along the social divide, are feeling the resultant hollow pain in our chests.

How do we fix this? Not by legislation—because we’re talking about souls and habits, not prohibitions and mandates.

A decade ago, my wife Melissa and I decided to “put down roots” by reinvesting in my hometown of Fremont, Neb., despite—and partly because of—the fact that it is showing signs of economic decline. The town’s biggest employers are a pig plant and a chicken plant, and the share of public-school students getting free or reduced-price lunch is spiking. Wealthier people are leaving our town of 26,000. Although first-generation immigrants are adding a youthful vitality, there is serious social conflict over the pace of change.

Melissa and I have worked with our children to develop an imperfect, provisional strategy for engaging more meaningfully with our own community. We’ve tried, through our church and other local groups, to become friends with people from every race and income bracket in Fremont. We’ve begun doing more community service, and we’ve made an important symbolic commitment by buying cemetery plots here. It’s not nearly enough—and Melissa carries most of the burden because I’m off in D.C. too many nights a week—but it’s a start.

Just as happened under rapid industrialization and urbanization, we of the digital age must find creative ways to replenish social capital. Whenever there’s a disruption, new forms of republican virtue—with a lowercase R—must emerge, flowing from and reinforcing habits of mutual affection and understanding.

If too many Americans feel like we’re not “in this together” right now, it’s because we’re not. We are screaming at each other, and the country no longer has enough real social texture to absorb and wick away the hatred. The only way out is to rebuild our communities and launch new ones—one person-to-person relationship and one local institution at a time.

To see this article, click read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online