By: Matt Ridley – wsj.com – March 6, 2023

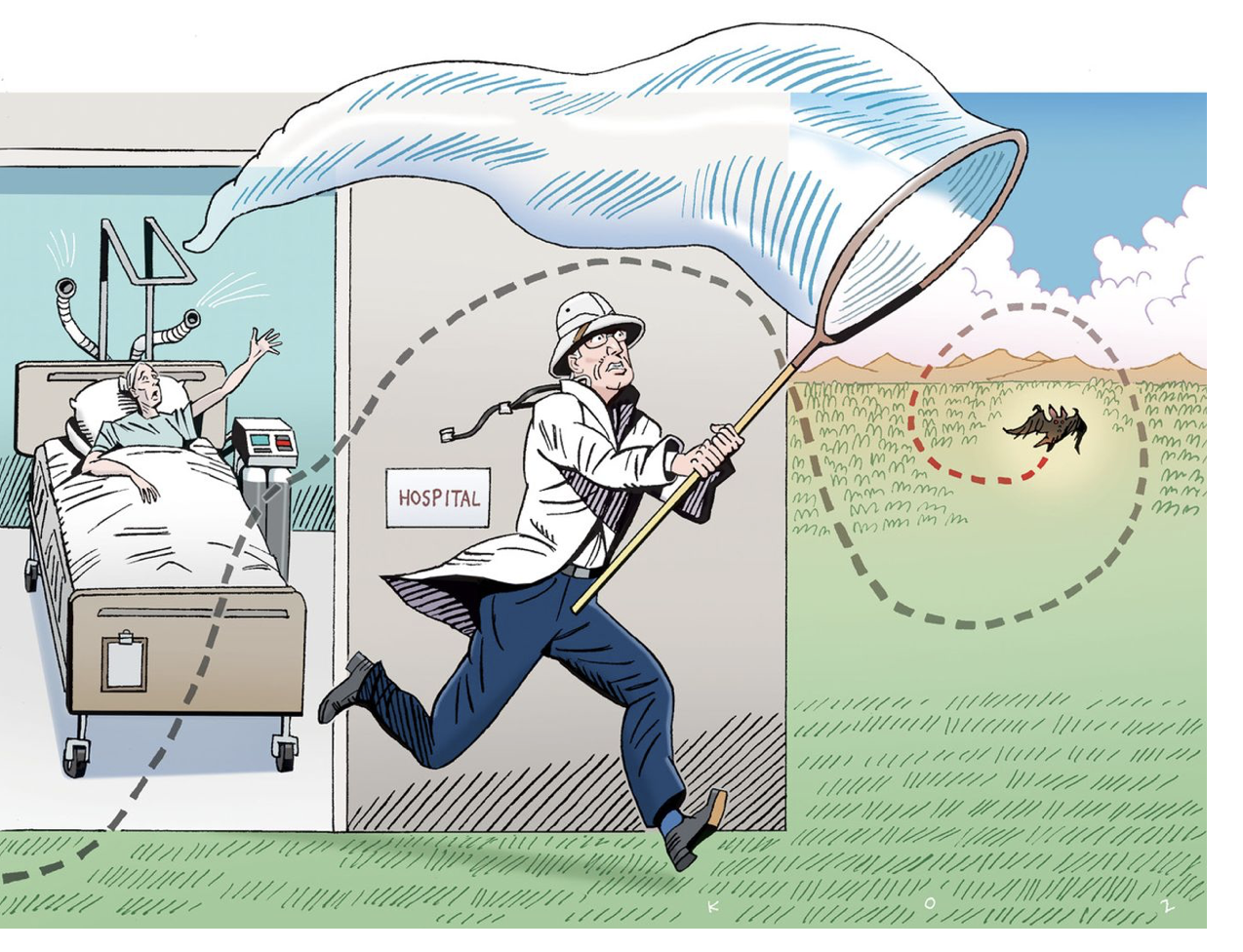

The threat to humans from animal viruses is small. The financial incentive to pretend otherwise is large.

That assumption is almost certainly false. A new report from the University of Leeds, prepared in part by former World Health Organization executives, finds that the claims made by the G-20 in support of this agenda either are unsupported by evidence, contradict their own cited sources, or fail to correct for improved detection of pathogens. Over the past decade the burden and risk of spillover has been relatively small and probably decreasing. The Leeds authors conclude: “The implication is that the largest investment in international public health in history is based on misinterpretations of key evidence as well as a failure to thoroughly analyze existing data.”

The Covid-19 pandemic, far from justifying the diversion of funds into tackling spillovers, may undermine this narrative. If Sars-CoV-2 entered the human species through a laboratory accident, as the WHO, parts of the U.S. intelligence community and many scientists agree is possible, then it wouldn’t count as a natural spillover. Worse, it would be more than a case of research gone wrong. It would be pandemic-prevention research gone wrong. The search for spillover risk may have caused a dangerous spillover.

The Leeds team examined eight reports commissioned by the G-20, the WHO and the World Bank that all claim spillovers of dangerous viruses from wildlife are increasing. A June 2021 report prepared by the WHO and World Bank predicts that “outbreaks of pathogens of pandemic potential are set to continue to increase in frequency for the foreseeable future.” A March 2022 G-20 reportstates that “even as we fight this pandemic, we must face the reality of a world at risk of more frequent pandemics.” A 2022 World Bank report talks of “an accelerating trend of pandemics.” A November 2023 WHO report claims that “pandemics of infectious diseases are occurring more often, and spreading faster and further than ever.”

The Leeds team found the reports “significantly mischaracterized” their own sources. The common claim in all the reports that climate change and deforestation increase the risk of virus spillover is poorly supported by the evidence. One of the studies cited by the World Bank found the opposite: “More intact ecosystems may be associated with a higher rate of zoonotic spillover events” because there is more wildlife in them.

In any case, many regions are now seeing net reforestation, rather than deforestation. The rate of forest regrowth is especially rapid in southern China, where SARS and Covid emerged, because of migration to urban areas.

New techniques have improved detection of viruses in recent decades. HIV probably spilled over decades before it was detected. Nipah, a virus transmitted to humans and pigs by fruit bats in south Asia, probably spilled over many times before it was identified in the 1990s. (It had previously been misdiagnosed as Japanese encephalitis.) The largest Nipah outbreak killed only 110 people. Yellow fever and plague, also cited as examples of spillover by WHO, have infected human beings for centuries with outbreaks far more severe than today.

Even viruses that are new to the human species kill few people compared with the vast annual toll of malaria and tuberculosis. Ebola killed some 12,000 in the worst outbreak. MERS and SARS killed fewer than 900 each, and Zika fewer than 400. Avian flu kills fewer than 80 a year. These numbers are falling, not rising. A database on which the World Bank relied shows, according to a summary by the Leeds authors, a “major reduction in reported medium (>100 cases) and large (>1000 cases) outbreaks over the period 2009 to 2017.”

It is a misconception that population growth or prosperity leads humanity to encroach on wildlife habitats. The poorest people in Africa encroach on forest wildlife by hunting for bush meat; when they grow richer, they shop for chicken or pork instead. Humans visited bat caves more frequently in the distant past. The exception is scientists, who have only recently begun rooting around in bat caves. As for climate change, wildlife responds by moving, adapting or dying out, not by taking refuge in cities, as is sometimes claimed. Nor does the growth of cities necessarily represent a greater risk of transmission of new viruses. As the Leeds team put it, while “urbanization accelerates speed of inflection by placing a greater number of human bodies in proximity, it can also facilitate a more targeted response.”

The Leeds team concludes that “the world is getting better at detecting outbreaks, and identifying and distinguishing pathogens, whilst also improving capacity to address these challenges.” As for Covid-19, the authors say it looks like “an outlier in the context of recent outbreak trajectory, rather than indicative of a trend.” The prospect of spending $31 billion a year on pandemic prevention, a third of which would be new money and a third diverted from other programs, provides an incentive for international bureaucrats to ignore or misrepresent evidence that the problem is small.

But a dollar spent on spillover can’t be spent on something else, and the evidence is clear that sanitation, nutrition and vitamins are more cost-effective ways to save lives in poor countries—from infectious diseases as well as other causes. In an illustration of the opportunity cost, Vanuatu was on the brink of eradicating malaria before its public-health staff were diverted toward Covid. Malaria has erupted again in the 80-island archipelago.

While the diversion of funds to prevent natural virus spillover turns out to be based on flawed data, the need for regulation of scientific research aimed at finding and manipulating potential pandemic viruses is based on real data. Whether Covid began in a laboratory or not, risky gain-of-function research with SARS-like viruses did happen at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, some of it at low biosafety levels. A report released Feb. 28 by the Pathogens Project, part of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, draws up detailed recommendations for how to prevent scientists taking unacceptable risks on behalf of humanity. That is the greater threat.

To see this article in its entirety and to subscribe to others like it, please choose to read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online