In 2011, my parents gave me a sum of money that was both outrageous and, in the real estate terms of major cities, quite reasonable: 10 percent down on the 250-square-foot apartment I still own in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. While I was conflicted about taking it, there wasn’t much of a question about whether I’d accept. My writing career (any writing career!) was inherently unstable; having a roof over my head that I could not only count on but would also help me build equity meant everything. And though I pay my monthly maintenance and mortgage on my own, as I did with my rent, that initial down payment would have taken me years to save, time that would have priced me out of the market.

“We’d leave you this money anyway; you might as well use it now!” my dad would say in conversations about how I should buy, and I’d remind him that he and my mom were never supposed to die. After I closed on my apartment, I’d gently correct people who asked if I’d mind telling them what I paid in rent that um, I actually owned, but I didn’t tend to divulge how I owned, exactly. Only my good friends, and those who asked point-blank, knew that.

I, like any savvy internetter, know full well how outrage against privilege (financial or otherwise) works: We railed against the entitled Refinery29 Money Diarist whose parents not only paid her rent, but who also gave her an allowance, supplemented by a second allowance from her grandfather. On the other side of the coin is Kylie Jenner, touted as self-made, at least according to that July Forbes cover, and very close to billionaire status. We railed against that, too, but for a different reason: “It is not shade to point out that Kylie Jenner isn’t self-made,” tweeted the writer Roxane Gay. “She grew up in a wealthy, famous family. Her success is commendable but it comes by virtue of her privilege.”

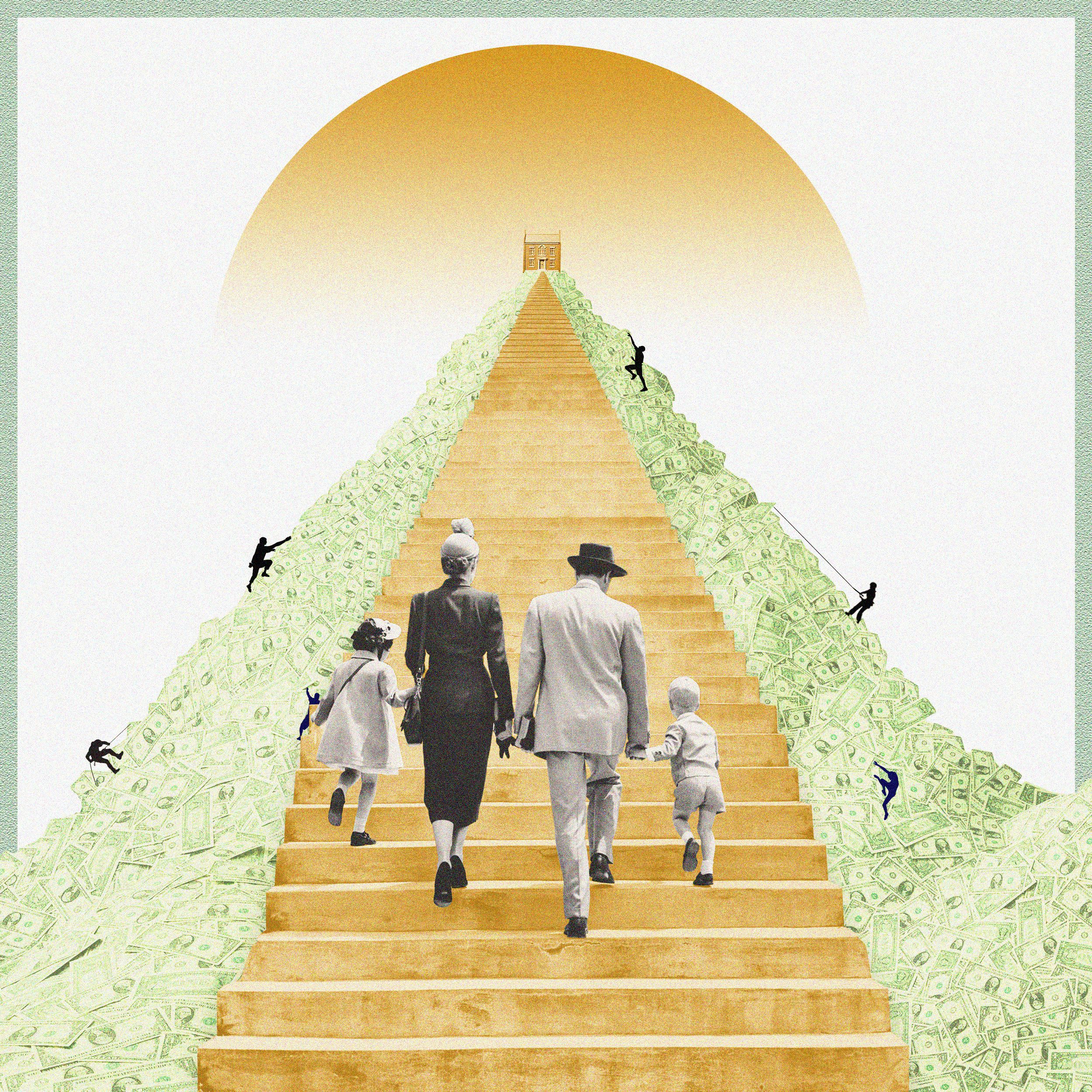

In the wake of the Refinery29 outrage, Jared Richards tweeted, “if your parents pay your rent, you have to put it in your Twitter bio,” garnering nearly 70,000 likes. But actually opening up these dialogues around money, privilege, success, and class is as complex as the threads weaving those four beasts together. Privilege is in part defined by where each of us stands; how we look at other people—whether it’s through their Instagram feed or the windows of their brownstone—involves our own psychology, experience, and situation in life. I’m no Kylie Jenner, but getting the down payment for your New York City apartment is as unimaginable to many as being a Kardashian is to me. Sure, it’s better for everyone to “just be honest,” but what does the truth actually look like?

Take a look around you at the lives you envy, the ones that make you boil with resentment, or fill you with insecurity about your own subpar existence: That adorable Brooklyn brownstone or chic-but-rustic upstate home; the career that YOUwant (and you should have, what are you doing wrong?); the impeccable wardrobe; the mid-century modern furniture; the international vacations; the time spent flitting between gorgeous hotels or going to boutique fitness classes or (seemingly) not working at all. Maybe it’s simply an ease of life indicating that whoever possesses it has been better at this game than you have. But how does anyone start their own company or buy a home, much less travel to Fiji, in a time of crushing student debt, when the job market is shifting at an out-of-control rate into a soulless gig economy, industries are dying left and right, we’re totally burning out, and we’re being replaced with robots. Health care costs are rising faster than you can make a doctor’s appointment, but that’s OK, because robots don’t get sick.

The writer and podcaster Gaby Dunn has a new book called Bad with Money: The Imperfect Art of Getting Your Financial Sh*t Together, a look at her own financial history and what she’s learned, along with thoughts on what we can all do better. “Everything is so broken!,” she tells me. “You hear about so many problems with medical debt, people being unable to buy a house, people saddled with student loans, the job market. It seems insurmountable. It’s hard for one person to make it out of the muck without a big systemic overhaul to help everyone else.” Meanwhile, in the penthouse upstairs, or perhaps on social media, people appear to be having the most glorious time. Is the Titanic sinking while the band plays on, or are some people just better with money?

As with any “meritocracy,” appearances are only a piece of the story. Wealth inequality has increased more in this decade than any other in American history, while economic mobility has done the opposite, as Matthew Stewart writes in an Atlantic article about the new American aristocracy. Money has always been passed down in families, but today, across America, parents who can are helping their grown children at unprecedented levels. A recent study from Merrill Lynch and Age Wave reported that 79 percent of the parents surveyed are providing financial support to their adult children, at an average $7,000 a year—making for a combined $500 billion annually. Increasing numbers of first-time home buyers in the U.S. are getting money from their parents for down payments. In a CreditCards.com survey of parents with children over the age of 18, three out of four helped their kids pay debts and living expenses, including rent, utilities, and cell phone bills. The help continues in death; roughly 60 percent of America’s wealth is inherited, though this, like the rest of privilege, skews heavily white: According to the authors of a 2018 study published in the American Journal of Economics and Sociology, the average inheritance for white families is over $150,000; for black families, it’s under $40,000.

Of course, helping your kid by providing a college education or paying a cell phone bill, or even paying for them to go on an extravagant vacation with you, is a far cry from leaving them $11.4 million (the amount rich folks can bequeath their kids tax-free in 2019). And, by the way, none of this means that children who accept help from their parents are lazy or entitled. Consider Daniella Pierson, 23, the founder and CEO of Newsette, a mini-magazine with 400,000 subscribers that she started when she was a sophomore at Boston University. When Pierson hit 100,000 subscribers a year in, she went to her parents, who run several successful car dealerships, with a business plan, asking for money. “They were reluctant. They’re completely self-made,” she says. Finally, they agreed to give her $15,000—a loan, with 5 percent interest. “After I graduated, we made over $25,000 in one month, and I wrote them a check,” Pierson says. “I was done with my loan.” Even though $15,000 is a comparatively small investment, her biggest fear was hearing “she’s only successful because of her parents.” Pierson admits, however, that there are multiple factors in anyone’s success: Her parents paid for her college tuition, and she was able to stay on their health insurance while building her business. Most of all, she had her parents as inspirations. “That’s really where my work ethic comes from,” she says.

Farnoosh Torabi, creator and host of the “So Money” podcast and author of When She Makes More: 10 Rules for Breadwinning Women, was able to graduate from college debt-free and buy her first home with the help of her parents. “I’m grateful that my parents gave me a head start, but I’m going to give myself the credit where it’s due,” she says. “I had the responsibility and appreciation for that and took it to the next level. If you look at the other side of the equation, there are plenty of people who came from privilege and are doing crap!”

To see the remainder of this article, click read more.

Source: Why the “Self-Made” Success Story Is a Myth — How Parents Help Children with Money

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online