Dozens of companies use smartphone locations to help advertisers and even hedge funds. They say it’s anonymous, but the data shows how personal it is.

By: Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Natasha Singer, Michael H. Keller & Aaron Krolik – nytimes.com – December 10, 2018

The millions of dots on the map trace highways, side streets and bike trails — each one following the path of an anonymous cellphone user.

One path tracks someone from a home outside Newark to a nearby Planned Parenthood, remaining there for more than an hour. Another represents a person who travels with the mayor of New York during the day and returns to Long Island at night.

Yet another leaves a house in upstate New York at 7 a.m. and travels to a middle school 14 miles away, staying until late afternoon each school day. Only one person makes that trip: Lisa Magrin, a 46-year-old math teacher. Her smartphone goes with her.

An app on the device gathered her location information, which was then sold without her knowledge. It recorded her whereabouts as often as every two seconds, according to a database of more than a million phones in the New York area that was reviewed by The New York Times. While Ms. Magrin’s identity was not disclosed in those records, The Times was able to easily connect her to that dot.

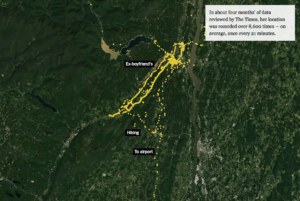

The app tracked her as she went to a Weight Watchers meeting and to her dermatologist’s office for a minor procedure. It followed her hiking with her dog and staying at her ex-boyfriend’s home, information she found disturbing.

“It’s the thought of people finding out those intimate details that you don’t want people to know,” said Ms. Magrin, who allowed The Times to review her location data.

Like many consumers, Ms. Magrin knew that apps could track people’s movements. But as smartphones have become ubiquitous and technology more accurate, an industry of snooping on people’s daily habits has spread and grown more intrusive.

Lisa Magrin is the only person who travels regularly from her home to the school where she works. Her location was recorded more than 800 times there, often in her classroom .

A visit to a doctor’s office is also included. The data is so specific that The Times could determine how long she was there.

Ms. Magrin’s location data shows other often-visited locations, including the gym and Weight Watchers.

In about four months’ of data reviewed by The Times, her location was recorded over 8,600 times — on average, once every 21 minutes.

By Michael H. Keller and Richard Harris | Satellite imagery by Mapbox and DigitalGlobe

At least 75 companies receive anonymous, precise location data from apps whose users enable location services to get local news and weather or other information, The Times found. Several of those businesses claim to track up to 200 million mobile devices in the United States — about half those in use last year. The database reviewed by The Times — a sample of information gathered in 2017 and held by one company — reveals people’s travels in startling detail, accurate to within a few yards and in some cases updated more than 14,000 times a day.

[Learn how to stop apps from tracking your location.]

These companies sell, use or analyze the data to cater to advertisers, retail outlets and even hedge funds seeking insights into consumer behavior. It’s a hot market, with sales of location-targeted advertising reaching an estimated $21 billion this year. IBM has gotten into the industry, with its purchase of the Weather Channel’s apps. The social network Foursquare remade itself as a location marketing company. Prominent investors in location start-ups include Goldman Sachs and Peter Thiel, the PayPal co-founder.

Businesses say their interest is in the patterns, not the identities, that the data reveals about consumers. They note that the information apps collect is tied not to someone’s name or phone number but to a unique ID. But those with access to the raw data — including employees or clients — could still identify a person without consent. They could follow someone they knew, by pinpointing a phone that regularly spent time at that person’s home address. Or, working in reverse, they could attach a name to an anonymous dot, by seeing where the device spent nights and using public records to figure out who lived there.

Many location companies say that when phone users enable location services, their data is fair game. But, The Times found, the explanations people see when prompted to give permission are often incomplete or misleading. An app may tell users that granting access to their location will help them get traffic information, but not mention that the data will be shared and sold. That disclosure is often buried in a vague privacy policy.

“Location information can reveal some of the most intimate details of a person’s life — whether you’ve visited a psychiatrist, whether you went to an A.A. meeting, who you might date,” said Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat of Oregon, who has proposed bills to limit the collection and sale of such data, which are largely unregulated in the United States.

“It’s not right to have consumers kept in the dark about how their data is sold and shared and then leave them unable to do anything about it,” he added.

Mobile Surveillance Devices

After Elise Lee, a nurse in Manhattan, saw that her device had been tracked to the main operating room at the hospital where she works, she expressed concern about her privacy and that of her patients.

“It’s very scary,” said Ms. Lee, who allowed The Times to examine her location history in the data set it reviewed. “It feels like someone is following me, personally.”

The mobile location industry began as a way to customize apps and target ads for nearby businesses, but it has morphed into a data collection and analysis machine.

Retailers look to tracking companies to tell them about their own customers and their competitors’. For a web seminar last year, Elina Greenstein, an executive at the location company GroundTruth, mapped out the path of a hypothetical consumer from home to work to show potential clients how tracking could reveal a person’s preferences. For example, someone may search online for healthy recipes, but GroundTruth can see that the person often eats at fast-food restaurants.

“We look to understand who a person is, based on where they’ve been and where they’re going, in order to influence what they’re going to do next,” Ms. Greenstein said.

Financial firms can use the information to make investment decisions before a company reports earnings — seeing, for example, if more people are working on a factory floor, or going to a retailer’s stores.

To see the remainder of this article, click read more.

Source: Your Apps Know Where You Were Last Night, and They’re Not Keeping It Secret

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online