Penna Dexter

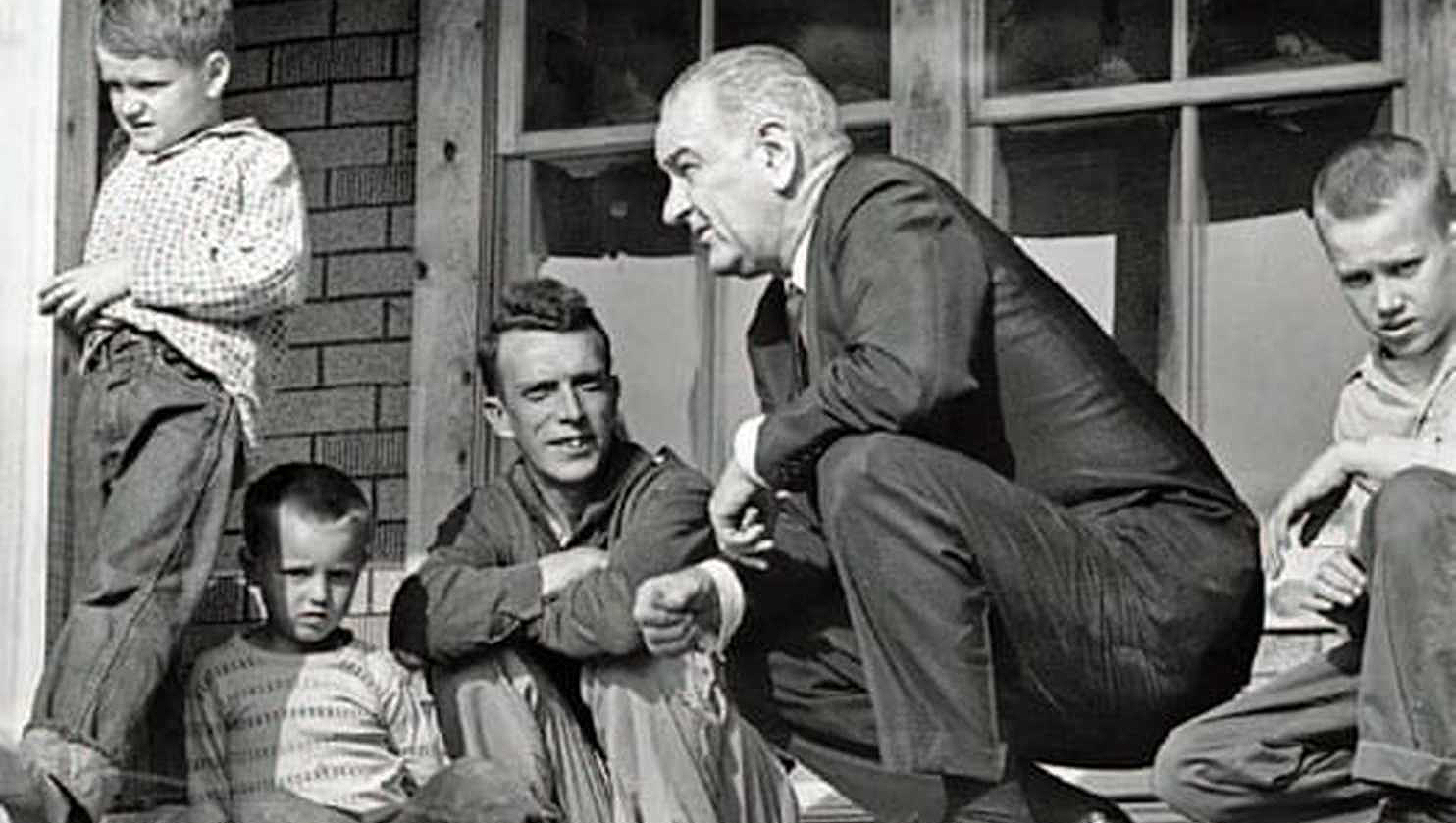

We often hear that the War on Poverty, launched during the administration of President Lyndon Johnson, hasn’t reduced poverty.

It’s true that, since 1966, the first year that saw significant spending in the War on Poverty, the poverty rate as reported by the US Census Bureau hasn’t budged. It remains at about 14 percent of the population.

During that time, government transfer payments to low-income families increased in real dollars from an annual average of about $3100 per person to about $34,000. But the transfer payments emanating from means-tested programs including food stamps, Medicaid, the portion of Medicare going to low-income families, Children’s Health Insurance, the refundable portion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, and 87 others don’t count as income in figuring the poverty rate. The government counts as income what is actually earned plus anything low-income Americans receive from Social Security or unemployment insurance.

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Former US Senator Phil Gramm and John Early, who served in the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, state that, “If government counted this missing $1.5 trillion in annual transfer payments, the poverty rate would be less than 3 percent.”

“Transfer payments,” write Senator Gramm and Mr. Early, “essentially have eliminated poverty in America.” But, the War on Poverty was waged, not just to raise living standards, but also to make the poor more self-sufficient and able to operate in the mainstream of the American economy. In this, it has failed. Before it began, working aged heads of families in the bottom fifth of the population often held jobs. Since that time, there’s been a precipitous decline in work among low-income Americans who receive benefits. Now, in that bottom quintile, really, no one works.

Misters Gramm and Early conclude: “Government programs replaced deprivation with idleness, stifling human flourishing.” These folks may have food, homes, cars, TV and internet, but lack the tremendous good that comes from gainful employment.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online