By: The Editorial Board – wsj.com –

Many states are starting to lift their shutdown orders, but some governors are still insisting they need more testing to do so. The Trump Administration on Monday responded by laying out all of the country’s testing capacity. But no amount of testing by itself will stop the virus from spreading. States will need a cocktail of strategies to limit the spread of infections.

***

Testing problems did hamper the initial U.S. response and allowed the coronavirus to spread undetected for weeks in Seattle and New York City. Testing was at first limited to people who had knowingly come into contact with infected individuals, and then it took days to get results. President Trump too often overpromised what the feds couldn’t deliver.

But testing has dramatically ramped up, and the Food and Drug Administration has now approved 70 coronavirus tests—about four times more than it approved for the H1N1 flu virus in 2009. More tests per capita have been performed in New York City than in Singapore, South Korea and Australia.

Hospitals and labs have performed about 1.6 million tests in the past week, according to the Covid Tracking Project. The White House coronavirus task force presentation shows that most states with the biggest risks have the capacity to test 60% to 80% of their population each month. Gov. Andrew Cuomo last week said tests would be available at some 5,000 pharmacies across New York.

Credit private innovation. Abbott Labs says it had shipped one million tests for its 18,000 portable machines in the field that can return results in five minutes and is manufacturing 50,000 kits a day. U.S. hospitals have more than 5,000 Cepheid fast-testing machines, which require no special training. Some 93% of the U.S. population lives within 10 miles of a test site.

As testing has expanded, the choke-point now is a shortage of nose swabs and chemical reagents to process specimens. But these shortages are easing thanks to FDA flexibility and the resourcefulness of private industry. The FDA is allowing polyester swabs that are easier to make. As flu season ebbs, swab manufacturers can prioritize coronavirus tests.

The FDA has also approved a new saline solution for transporting specimens, and more diverse testing platforms will ease reagent shortages. The agency recently approved the first point-of-care saliva tests that can be processed in large batches within hours as well as an at-home short-swab testing kit.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine said last week that more swabs and reagents will enable the state to increase testing by six-fold over the next month. Democrats are criticizing the Trump Administration for not taking control of the many different testing supply chains, but then they complained that the federal government was too slow to open testing to private labs. They can’t have it both ways.

As supply-chain bottlenecks are sorted out, the kvetching about tests by many governors sounds increasingly like an excuse not to take responsibility for a plan to reopen. “You are using a free-market model in a public health emergency,” Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly, a Democrat, recently said. Virginia Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam has called President Trump “delusional” for suggesting there’s enough coronavirus testing capacity for states to safely reopen.

What’s delusional is to suggest that states must be able to test every citizen on demand. As Anthony Fauci has explained, someone may test negative one day but positive the next. The incubation period can be between two and 14 days, which means infections can easily be missed even with widespread testing.

Many states including California, New York and Massachusetts are training people to track down contacts of people who test positive. But contact tracing also isn’t a magic bullet because of the virus’s easy transmission and large share of asymptomatic individuals. Apple and Google have devised a bluetooth-based app that can help folks who test positive trace their transient contacts. The question is what to do with this information.

Should everyone who comes within six feet of someone who tests positive be tested and quarantined? Should people get a test immediately upon learning about their exposure or 14 days after it occurred? What should people do if they are repeatedly exposed to infected individuals, as likely will happen in dense urban areas like New York City?

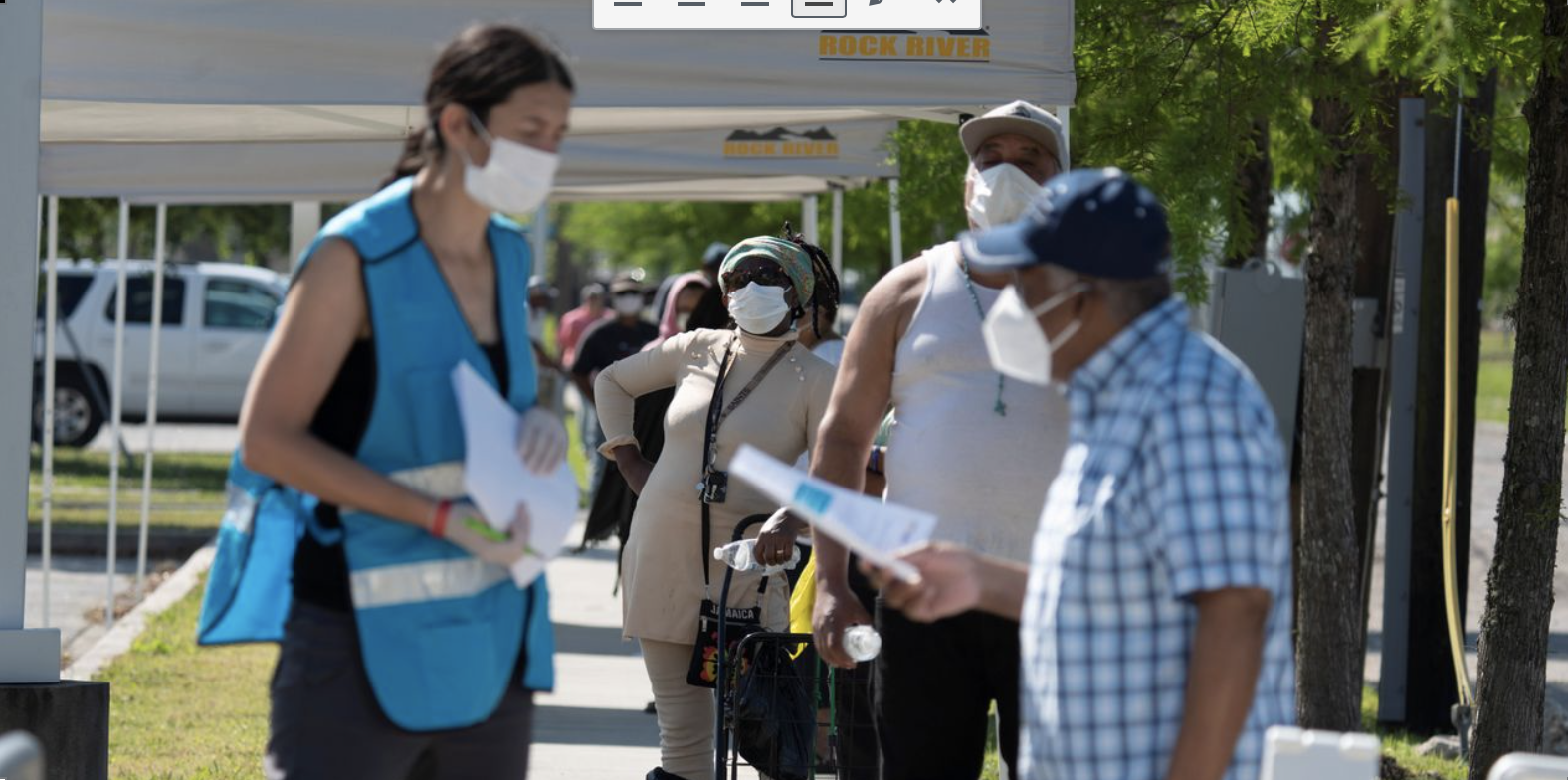

Such quandaries make testing far from the deus ex machina that many claim. What states need is the capacity to focus testing when there are flare-ups, and to conduct surveillance testing of vulnerable communities like low-income populations with more underlying health conditions and nursing homes, as the White House task force has recommended.

Workplaces will also want to test workers who develop cold or flu-like symptoms. Other public hygiene strategies will be needed and can build public confidence that it is safe to go back to work, shop or eat out. By all means keep ramping up testing capacity, but it shouldn’t be an excuse to keep the economy in cold storage.

To see this article and subscribe to others from WSJ, click read more.

Source: Testing Isn’t Everything – WSJ

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online