For a sense of how far the left will go to enforce climate-change orthodoxy, read the recently released “Common Interest Agreement” signed this spring by 17 Democratic state attorneys general. The officials pledged to investigate and take legal action against those committing climate wrongthink. Beginning late last year, the attorneys general of Massachusetts, New York and the U.S. Virgin Islands, all signatories to the agreement, issued broad-ranging subpoenas against Exxon Mobil and conservative think tanks. They sought documents and communications related to research and advocacy on climate change.

Concerned that these investigations were designed to chill First Amendment rights, the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology issued its own subpoenas. In mid-July the committee, led by Rep. Lamar Smith (R., Texas), asked the attorneys general to produce their communications with environmental groups and the Obama administration about their investigations.

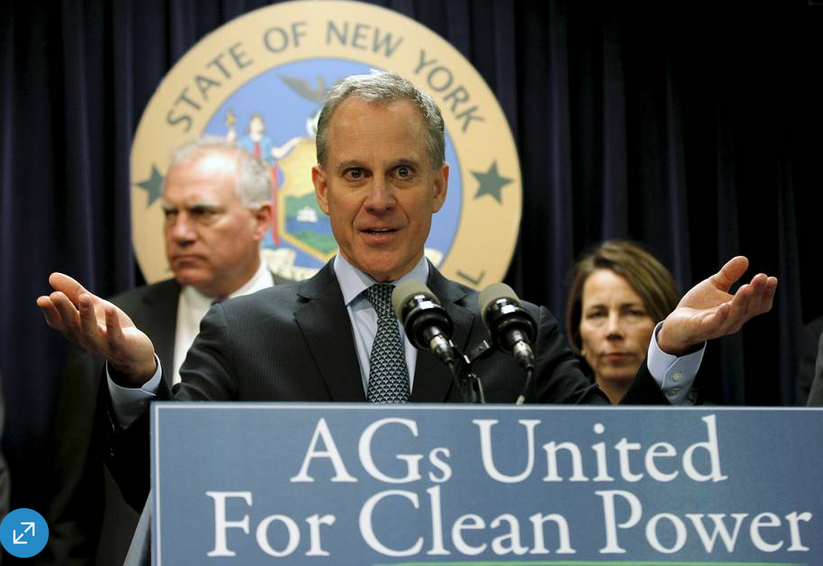

They have indignantly refused to comply. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman claimed, in a July 13 letter to Mr. Smith, that the committee was “courting constitutional conflict” by failing to show “a due respect for federalism.” Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, in a similar letter dated July 26, asserted that the subpoenas are “unconstitutional” because they are “an affront to states’ rights.”

This view is utterly wrong. Federalism is a critical component of the constitutional architecture. The federal government exercises only limited and enumerated powers, and the states, under the Tenth Amendment, possess all other powers “not delegated to the United States.” But when the federal government acts within its delegated powers, it is entitled to supremacy over the states.

The Supreme Court has long recognized Congress’s power to investigate any matter within its legislative or oversight competence. With that comes a corresponding power to enforce its inquiries. The justices wrote in Barenblatt v. U.S. (1959) that the scope of Congress’s power of inquiry “is as penetrating and far-reaching as the potential power to enact and appropriate under the Constitution.”

Similarly, in McGrain v. Daugherty (1927), the court held that “the power of inquiry—with the process to enforce it—is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function.” That’s why lawmakers passed a law to make contempt of a congressional subpoena a crime, punishing anyone who willfully refuses to answer “any question pertinent to the question under inquiry.”

The subpoenas to state attorneys general regarding their climate crusade easily fall within Congress’s legislative and oversight competence. The House Science Committee has jurisdiction over matters relating to scientific research. Its rules authorize the chairman to issue subpoenas on behalf of the committee.

Further, Congress has ample authority to investigate and sanction violations of First Amendment rights that are committed by state officials. For instance, the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 includes a provision—lawyers often call it simply “section 1983,” referring to its place in Title 42 of the U.S. Code—authorizing monetary damages against state officials who infringe a constitutional right.

Congress’s broad investigatory power clearly extends to state officials. In February, the House Oversight Committee compelled Darnell Earley, the emergency manager of Flint, Mich., to testify on the contamination of that city’s drinking water. Mr. Earley initially refused to appear, but he quickly acceded to its subpoena after the committee’s chairman, Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R., Utah), threatened to call the U.S. Marshals to “hunt him down.”

Under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, privileges grounded in state law—such as the attorney-client privilege or work-product privilege—are not binding on the federal government. The letter to Rep. Smith from the Massachusetts attorney general, for example, argued that the committee’s subpoena seeks documents that are “either attorney-client privileged” or “protected from disclosure as attorney work product.” Congress is obligated to honor neither of those state-law privileges.

When Congress subpoenas the White House or agencies in the executive branch, there is a delicate balancing of competing constitutional interests. This is because the executive often refuses to comply by invoking a presidential privilege grounded in Article II of the Constitution.

But there is no such difficult constitutional balancing required here. When Congress subpoenas state attorneys general in the rightful exercise of its legislative and investigative power, all assertions of state authority give way because of the Supremacy Clause. No state official—whether judicial, legislative or executive—may resist a legitimate federal command.

Throughout the Obama administration, congressional powers have been increasingly usurped by the executive. The White House has unilaterally rewritten statutes, ignored congressional subpoenas and arrogated to itself the power of the purse. These actions have too often received the blessing of congressional Democrats, who have allowed partisanship to override their fidelity to the Constitution and their institutional self-interest.

To begin restoring Congress’s constitutional authority, the House of Representatives should push back against these state attorneys general and vigorously litigate to enforce the Science Committee’s subpoenas.

Ms. Foley is a constitutional law professor at Florida International University College of Law.

By Elizabeth Price Foley, wsj.com

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online