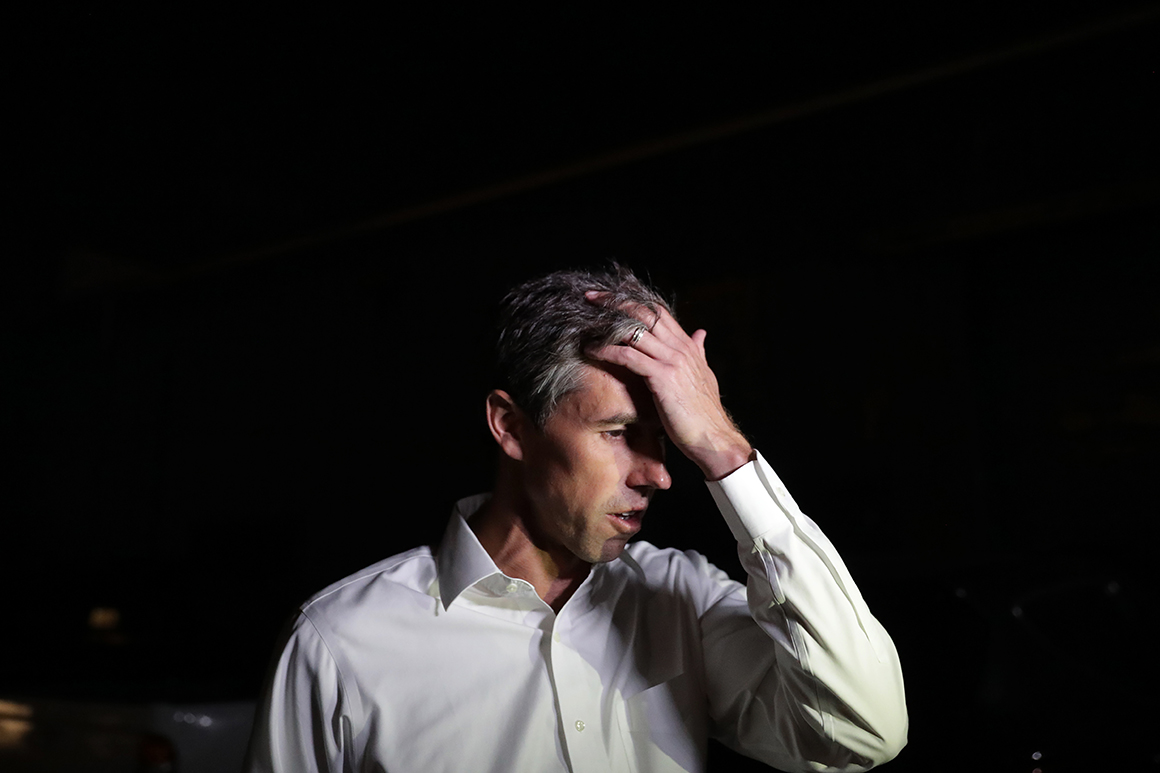

By: Tim Alberta – politico.com – November 4, 2018

In March 2017, a little-known Democratic congressman named Beto O’Rourke proposed something unusual to Will Hurd, a Republican colleague from a neighboring district: that they rent a car and embark on a 24-hour, 1,600-mile road trip from San Antonio to Washington. Their live-streamed odyssey wound up attracting blushing news coverage and evoking the bipartisan companionship of a bygone era. For Hurd, a pragmatic, swing-district moderate with numerous Democrats employed on his staff, the cross-aisle kumbaya was routine; few lawmakers hug the middle so tightly. For O’Rourke, the demonstration was less likely; he had done little to distinguish himself in the House of Representatives, and what reputation he owned was not that of a centrist. He won his congressional seat in 2012 by running to the left of an incumbent Democrat—a moderate Hispanic who warned voters of the El Paso councilman’s ultra-progressive policies—and spent the ensuing years compiling a safely liberal voting record.

Two weeks later, however, the strategic rationale behind the bipartisan road trip was manifest. “Regardless of party or background or geography or any other difference that someone might want to highlight, we all have this in common,” O’Rourke said in announcing his candidacy for U.S. Senate. “We’re Americans. We’re Texans. We want what’s good for this state. We want what’s good for this country.” In running against Ted Cruz, a name and a political brand synonymous with brutal partisanship, O’Rourke would represent the antidote: comity instead of chaos, agreeability instead of animosity, decorum instead of demolition.

In selling a symbolic candidacy, the Hurd roadshow was foundationally essential. But it wasn’t enough. To score the biggest upset of 2018, O’Rourke would need a brand that reinforced his rejection of status quo politics. So he created one—a campaign that rejects corporate money, that avoids negative attacks, that refuses to employ pollsters or consultants. And it worked. By offering a cause rather than a candidacy, O’Rourke convinced America that a Texas Democrat could win statewide for the first time since 1994. A staggering $70 million flooded into his campaign. Celebrities came calling on a first-name basis. LeBron James made the black-and-white “Beto” signage famous. National reporters took turns deifying the skateboarding, punk-rocking congressman. And all the while, O’Rourke was flatlining. When Quinnipiac polled the race in April, after he clinched the Democratic nomination, he registered at 44 percent; in July, the same poll pegged him at 43 percent; it was 45 percent in September; and 46 percent in late October. Whenever the race has tightened, it’s due to Cruz dropping below 50 percent. In dozens of public and private surveys this cycle, O’Rourke has never broken 47 percent.

Somewhere along the line, the rock-concert crowds and record-setting fundraising and JFK comparisons obscured a basic contradiction between Beto O’Rourke the national heartthrob and Beto O’Rourke the Texas heretic. While the coastal media’s narrative emphasized his appeals to common ground, framing him as an Obamaesque post-partisan figure, the candidate himself tacked unapologetically leftward. He endorsed Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for all” plan. He called repeatedly for President Donald Trump’s impeachment—a position rejected by Nancy Pelosi, and nearly every other prominent Democrat in America, as futile and counterproductive. He flirted with the idea of abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement. He took these positions, and others, with a brash fearlessness that reinforced his superstardom in the eyes of the Democratic base nationwide. But it likely stunted his growth among a more important demographic: Texans.

Over the past six months, I spoke with a host of Texas Republicans about the U.S. Senate race. Many of them dislike Cruz. Some of them privately hope he loses. And all of them are baffled by the disconnect between the superior branding of O’Rourke’s candidacy and what they see as the tactical malpractice of his campaign.

In their view, Cruz is uniquely vulnerable, having alienated Texans of all ideological stripes with his first-term antics—and especially those affluent, college-educated suburbanites repelled by Trump. The senator has long lagged 10 to 15 points behind Governor Greg Abbott at the top of the ticket; Cruz’s internal modeling has consistently demonstrated there are several hundred thousand voters committed to Abbott but not to him. This is the paradox of the Texas Senate race: Though it’s clear a significant bloc of soft Republicans and conservative-leaning independents are open to rejecting the incumbent on Tuesday, it’s equally clear the challenger has done little to move them. The Quinnipiac poll in April showed O’Rourke pulling 6 percent of Republicans; by late October that number was 3 percent. And while there are signs to suggest he will win more votes than a traditional Democrat in the metropolitan areas of Dallas and Houston and San Antonio, O’Rourke is almost certain to underperform in the rural and exurban areas of the state.

The campaign is a study in extreme contrasts: Cruz, the cartoonishly unlikeable conservative whose machine-like enterprise is run by a platoon of political gurus, versus O’Rourke, the obnoxiously likeable liberal whose garage-band effort is guided by gut instinct and raw emotion. Nothing is certain in such a volatile political climate, and there have been indications of a tightening race in the campaign’s final days. Cruz learned first-hand in 2016 that an organizational advantage doesn’t guarantee victory; O’Rourke can draw inspiration from Trump, of all people, in proving the pollsters wrong. If O’Rourke wins, he will have revealed a blueprint for animating the base and turning out new voters. But if he loses—as Texas insiders in both parties expect—the autopsies will speak of a strategically imbalanced campaign that did too much mobilizing and not enough persuading.

“Despite all of Cruz’s problems—and there are plenty—here’s a guy who’s running around talking about Medicare for all, and impeaching Trump, and abolishing ICE. And it’s killing him,” Karl Rove, the former senior adviser to George W. Bush, told me in Austin this summer. “Even for people who dislike Cruz, impeaching Trump strikes many of them as terrible for the country. I’ve got friends and family members who may not vote for Cruz. They don’t like Cruz. But Beto isn’t contesting them. I mean, it’s just weird.”

David Axelrod, the former senior adviser to President Barack Obama and Rove’s counterpart as the Democratic Party’s strategic elder statesman, said O’Rourke “has staked out some positions that are difficult positions for some of these voters in the middle to embrace,” adding, “I think one of the strengths of O’Rourke’s candidacy is that he hasn’t shaded his positions. But I acknowledge that may be a problem for some of these independent and moderate Republican voters and conservative Democrats.”

Turning out base voters is job No. 1 for any campaign. But rallying Democrats against Cruz was never the difficult part of defeating him. In 2012, Cruz’s general election opponent, Paul Sadler, captured 41 percent of the vote despite having no name recognition and raising roughly $700,000 for the entire election. O’Rourke raised 54 times that amount in the third quarter alone. Yet if the polling holds up, O’Rourke stands to improve on Sadler’s showing by just 3 or 4 points.

Maybe 45 percent is simply the ceiling for a Democrat in Texas. But this is overly simplistic. Trump won Tennessee by 26 points—nearly three times the margin of his Texas victory—and that state’s U.S. Senate race has been a dead heat, in large part because the Democrat, former governor Phil Bredesen, is selling a smartly packaged centrism. If O’Rourke loses, Texas might remember him for being singularly positioned to break that ceiling—running in an advantageous environment, against a damaged incumbent, bringing historic resources to bear, at a moment of cultural and demographic transition in the state—and failing to capitalize.

“It’s the worst campaign I’ve ever run against—or it’s the most brilliant,” Jeff Roe, Cruz’s chief strategist, told me. “He’s the best and worst opponent we could have faced. He energized the left and raised tons of money, but had no plan for how to spend it and no plan for building the sort of coalition needed for a Democrat to win in Texas. He ran an entire campaign without pursuing a single Republican vote.” (I reached out numerous times this fall to the O’Rourke campaign seeking an interview about their strategy; his spokesman, Chris Evans, told me after a recent debate in San Antonio that they were no longer talking to national media outlets.)

Given his sudden star power and prodigious fundraising abilities, there is already considerable momentum behind the theory that O’Rourke could segue from a losing Senate candidate to a top-tier presidential contender. But with a debate beginning to rage inside the Democratic Party over how best to defeat Trump—galvanizing the left or recapturing the center—a lopsided loss in Texas could force O’Rourke to answer tough questions relating to ideology and strategy. What exactly, inquiring and envious Democratic minds will want to know, did he do with that $70 million? Why wasn’t he barraging persuadable Republicans with mail and phone calls and door knocks? Could he not identify them because of his campaign’s refusal to invest in polling and data analytics? Did he consciously avoid playing on their issues, determining it was more profitable for his political future to lose as a liberal than compete as a moderate? What was to be gained by calling for Trump’s impeachment? And what evidence exists of his appeal to the middle of the electorate?

O’Rourke can’t be blamed for receiving media hype. He shouldn’t be penalized for hauling in historic sums of cash. And he didn’t ask to be vaulted into the 2020 presidential conversation. There is no disputing his intelligence, his magnetism, his earnestness. But elections are ultimately defined by wins and losses. Should O’Rourke suffer an anticlimactic defeat, given the fanfare surrounding his ascent, it will be fair to ask: Did the country’s best candidate run its worst campaign?

***

It was the perfect rebuttal to the perfect back-handed compliment. At the end of their first debate, in late September, the moderators asked Cruz and O’Rourke to compliment one another. O’Rourke observed that Cruz was a devoted father, saluting his public service at the expense of time with his young family. Cruz responded by praising O’Rourke as “passionate” and “energetic,” saying, “He believes in what he is fighting for.” He should have left it there. Instead, Cruz proceeded to compare O’Rourke to Bernie Sanders—ideologues who have crazy ideas, but who are “absolutely sincere” in believing them. “True to form,” O’Rourke said in disgust.

The moment crystallized their stylistic divergence: Cruz, the smarmy, calculating bare-knuckle brawler, landing a low blow against O’Rourke, the sincere, fresh-faced romantic. But there was more to it. Beneath the senator’s characteristic lack of self-awareness, his comment about O’Rourke reflected a combination of admiration and relief. Cruz clearly sees a little bit of himself in his challenger—a scrappy underdog rejecting conventional wisdom and running to his party’s flank on every issue. The difference is that Cruz played this role as a conservative in a Republican primary, whereas O’Rourke is a Democrat in a general election. “Sincerity is rare in politics. And I’m a true believer as well,” Cruz told me following the debate. “Both Beto and I are fighting for principles and values we believe in. The difference is, the principles and values I’m fighting for are also the ones the vast majority of Texans support.”

Hence the relief. Cruz always knew, coming off his dehumanizing defeat in the 2016 presidential race and heading into his Senate reelection, that Democrats would place a symbolic value on his scalp. He and his team braced for a challenge from the center. This is how Democrats win in red states—not by painting bold contrasts but by minimizing differences. So when O’Rourke entered the race, riding auspicious headlines from the Hurd road trip and preaching the politics of ceasefire, everything seemed to be on schedule. Until it wasn’t.

As his candidacy wore on, O’Rourke took ownership of positions further to the left—on guns, immigration, drug legalization—than anyone in either party expected. But he did so delicately, still elevating unifying thematic strokes over divisive policy specifics. Then came the Democratic primary in March. Despite being the de facto nominee, opposed by two unknowns who raised less than $10,000 between them, O’Rourke lost dozens of majority-minority counties to a 32-year-old “Berniecrat” with a Hispanic surname. The takeaway: He had work to do with the base.

Instead of pivoting to the center, as spring gave way to summer, the Democratic nominee hardened his positions. Where he had once hedged on his endorsement of “Medicare for all,” O’Rourke began forcefully championing a single-payer system. Where he once avoided impeachment talk, O’Rourke reiterated, on the day he and Hurd received an award for civility in politics, that Trump should be removed from office. Where he once carefully straddled the border-security debate, O’Rourke said he was open to abolishing ICE if its duties could be assumed elsewhere.

“Everything Beto did to define his campaign early on was about process and anti-corporatizing politics. It really wasn’t issue-based. It was about getting to every county in Texas, talking to people in small towns, hosting townhalls,” said James Aldrete, a Texas Democratic strategist who ran the Spanish-language media strategy for both Obama campaigns and for Hillary Clinton in 2016. As the campaign became more policy-heavy, Aldrete conceded, “He never made a political adjustment to reach out to the middle.”

For Cruz, this was manna from heaven.

[…]

To see the remainder of this article, click read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online