By: Ross Douthat – nytimes.com – January 19, 2019

One of the frustrating tics of our society’s progressive vanguard is the assumption that every evil it discovers was entirely invisible in the past, that this generation is the first to wrestle with dominance and cruelty.

This forgetting of human experience, this perpetual present-tenseness, pervades the latest flashpoint in the culture war over the sexes — the new guidelines for treating male pathology from the American Psychological Association.

The trouble with men, the guidelines argue, is that they’re violent and reckless, far more likely than women to end up in prison or dead before their time. But the deeper problem is they’re prisoners of “traditional masculinity,” which the guidelines describe as a model of manhood marked by “emotional stoicism, homophobia, not showing vulnerability, self-reliance and competitiveness.” This tough-guy ideal encourages “aggression and violence as a means to resolve interpersonal conflict,” and tempts men toward rape, drug abuse and suicide.

Are men so tempted? Certainly. The human male is a dangerous figure — generally bigger, stronger and more violent than the female of the species, free from the vulnerability that pregnancy entails, and therefore often distinctively threatening, to women and other men alike.

But the claim that a “traditional masculinity” encompassing “stoicism” and “self-reliance” necessarily makes this problem worse is mostly ahistorical rubbish — not least because in the actual history of the human race “traditional masculinity” as a single coherent category simply does not exist.

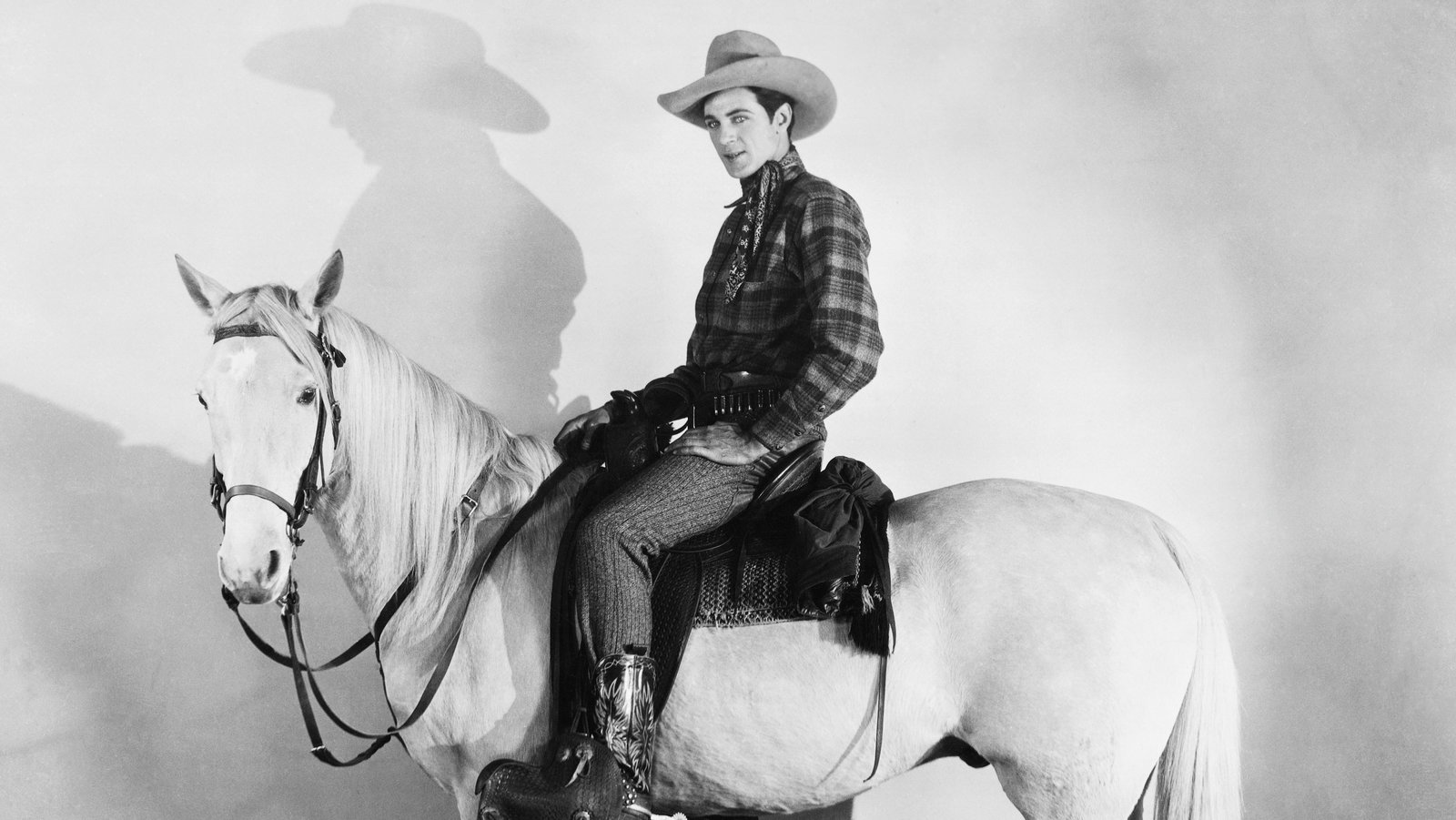

To pluck only Western examples, there is no single “traditional” model that can encompass strong, silent types and romantic poets, chivalric knights and laconic cowboys, the sorrowing Young Werther and the stiffened upper lip, the machismo of the Mediterranean and the mysticism of the Celts, Jimmy Stewart and Cary Grant and John Wayne.

What actually exists in history, instead, are varying models that attempt to deal with masculinity’s dark side in different ways, by channeling, sublimating and containing male aggression. All these models are “traditional” in the sense they were forged in societies more sexist and patriarchal than ours. But they were also forged by cultures well aware of the problem of toxic, reckless, violent men, and very concerned with what to do about them.

Consider, just to pick a reasonably accessible example, the portraits of masculinity offered in the 19th century novel. The toxic bachelor is a fixture in its pages, from Wickham in “Pride and Prejudice” to Vronsky in “Anna Karenina” to Angel Clare in “Tess of the D’Urbervilles.” And Victorian novelists both male and female are consistently preoccupied with the question of how a healthier manhood can be embodied.

The stoic model critiqued in the A.P.A. guidelines is one attempted embodiment — but only one. There is also the romantic model, who channels lust into romantic idealism, aggression into artistic ambition or religious purpose. And then there is the gentleman, whose persona seeks to balance self-control with idealism, politesse with passion, holding all in synthesis.

The 19th-century canon doesn’t imply that a single model always works. In “Far From the Madding Crowd,” the hero, Gabriel Oak, is a stoic with a well-integrated romantic streak; his foil and rival for the heroine’s affections, William Boldwood, believes himself a stoic but discovers a romanticism he can’t control, with violent consequences. In “Pride and Prejudice,” Mr. Darcy’s gentlemanly self-conception needs the leaven of humility that only romance can provide. The plot of “Wuthering Heights” turns on the question of whether Heathcliff’s romantic appeal is really toxic.

Then, too, across the life-cycle the models may need to shift — romanticism tempered by stoicism for the young, the reverse for fathers of young children, and some gentlemanly combination in old age.

So every model has limits — but it’s folly to blame any or all of them for the pathologies they aspire to tame. (Stoicism, especially, doesn’t exactly seem oversupplied in America these days.) Yet that’s what contemporary progressivism is constantly inclined to do: Because the male archetypes were forged in more sexist eras, that sexism is regarded as a reason to reject the archetypes tout court, in the hopes of building some sort of New Progressive Man instead.

In overreaction to this rejection, conservatives in the Trump era have ended up defending a caddishness that would make Wickham blush, in the mistaken belief that they’re defending masculinity itself. But the New Progressive Man isn’t much of a success either: If you listen to liberal women complaining about the male-feminist cads and “soft-boys” in their dating pool, progressive culture seems to have ended up creating a lot of Uriah Heeps and Gilbert Osmonds — men pretending to reject the masculine vices, but really sublimating them into softer forms of exploitation.

The alternative, adapting the older archetypes to an era of greater equality between the sexes, is admittedly a difficult task. But it’s a better path than throwing out the older models, and all their wisdom with them, and then cursing Gabriel Oak and Gary Cooper because toxic masculinity hasn’t gone away.

To see this article, click read more.

Source: Opinion | In Search of Non-Toxic Manhood – The New York Times

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online