By:

Last year’s ESG backlash spawned a vigorous debate about the use of environmental, social and governance factors in capital allocation. I met with numerous state financial officers, pension-fund boards, policy makers and corporate leaders who solicited my perspectives and those of competing asset managers as they grappled with fiduciary questions relating to ESG.

These discussions appear to have prompted the Big Three asset managers—BlackRock, State Street and Vanguard—to undertake small reforms, likely aimed at mitigating legal liability risk. Vanguard withdrew from the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative (though it remains affiliated with at least four similar associations); BlackRock and State Street announced new proxy voter choice programs (albeit only for a fraction of client assets and thus far limiting third-party alternatives to proxy advisory firms that also promote ESG); all three began to offer greater transparency to states about their proxy voting policies (although they are still opaque about the content of most shareholder engagements, which Vanguard defines as “direct contact with companies to discourage undesirable corporate behavior”).

ESG is far from dead. But there may be a solution in sight to the ESG debate: disclosure to and consent from capital owners.

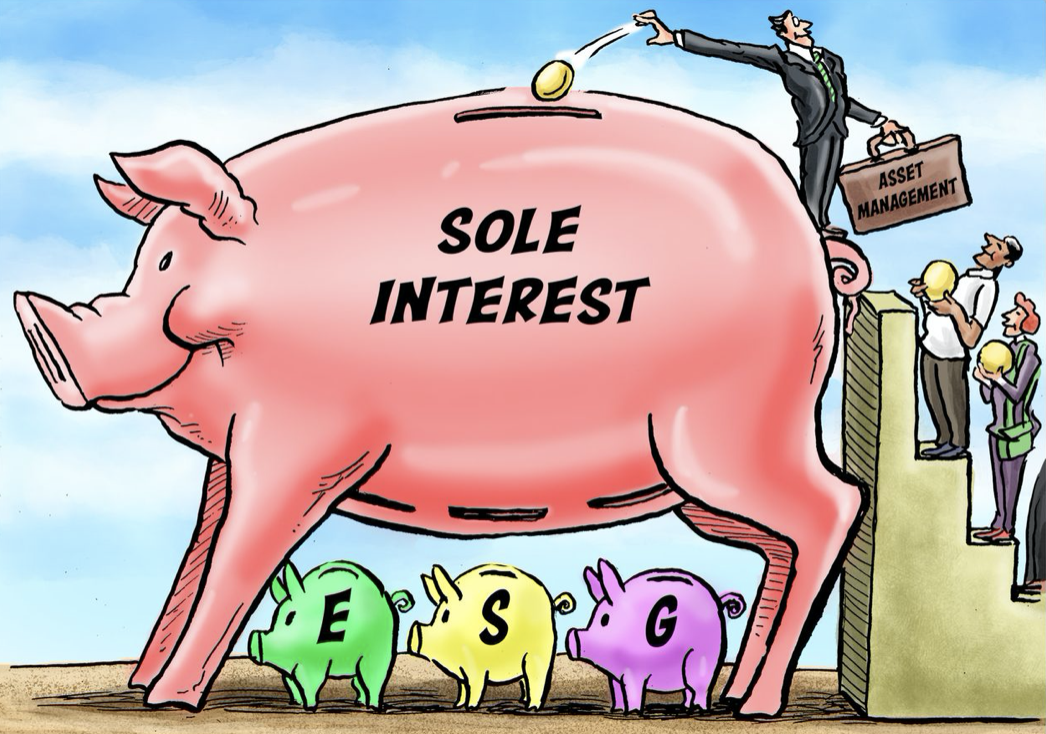

When investing money, individuals and other capital owners typically use financial intermediaries such as wealth managers and pension funds. These intermediaries are asset allocators, putting money into instruments such as index funds and mutual funds. Asset managers control these funds, buying stocks and bonds issued by publicly traded companies, and the boards of public companies allocate capital across corporate projects.

Wealth managers, pension funds and asset managers, unlike corporate directors, aren’t merely fiduciaries but also trustees. They are held to the highest legal standard—the “sole interest rule,” according to which a “fiduciary shall discharge his duties . . . solely in the interest of the participants and beneficiaries and . . . for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to participants and their beneficiaries,” as the U.S. Supreme Court put it in Central States, Southeast & Southwest Areas Pension Fund v. Central Transportation (1985).

The sole-interest rule is codified in state constitutions, statutes and case law. Trustees aren’t permitted to make investments to advance nonpecuniary interests or social causes but must act solely and exclusively to maximize retirees’ “financial benefits,” in the case of pension funds, as the Supreme Court held in Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer (2014). Because pension-plan trustees must be solely motivated by considerations of financial return, “mixed motive” investing is per se unlawful, as multiple state attorneys general noted in legal opinions last year.

Large asset managers integrate ESG objectives into their investment approaches in one of two ways. The first is through dedicated ESG or sustainability funds, which systematically exclude or underweight securities in disfavored sectors such as fossil fuels, tobacco and firearms. These funds represent a small portion of total assets under management—less than 6% as of last year in BlackRock’s case. If dedicated ESG funds accurately disclose their policies and the ultimate capital owners are informed of them before making investment decisions, there’s no legal problem. People are free to use their money to promote any social causes they like.

The second and more prevalent way that asset managers promote ESG is through “stewardship,” which refers to proxy voting and shareholder engagement. The largest asset managers use stewardship to promote ESG principles in all their portfolios, including non-ESG index funds.

In 2022, large asset managers including BlackRock voted in favor of implementing racial-equity audits at companies like Apple and Home Depot notwithstanding that the companies’ boards recommended against doing so. Similar examples abound with large asset managers imposing emissions caps, ESG-linked executive compensation and board diversity mandates across corporate America. Many capital owners strongly disagree with these objectives even though their money was used to support them.

As legal scrutiny intensified, ESG advocates started to claim that their proxy-voting and shareholder-engagement practices aren’t intended to advance social or political objectives but are motivated solely by financial considerations. Courts are likely to reject these claims given that candid descriptions of ESG invariably acknowledge that its goal is to advance “socially responsible,” “moral” or “social impact” outcomes and to allow investors to “put their money where their values are.”

An activist group pushing for Apple’s 2022 racial-equity audit said its mission was to “hold companies accountable for the ways they perpetuate white supremacy.” The Dutch nonprofit that in 2021 proposed an emissions cap at Chevron stated that its intention was to fight climate change. BlackRock and State Street used client funds to vote for both proposals, with no real financial justification for either. The boards of Apple and Chevron initially declined to adopt these proposals even though they enjoy broad legal deference, whereas the asset managers, bound by the sole-interest rule, voted for them. That maximizing value was their sole motivation isn’t credible.

But there’s a better defense for ESG-promoting asset managers: disclosure. Large asset managers are gradually becoming more transparent as pension-fund clients press them on their ESG practices. In recent months, BlackRock has written letters to officials in red and blue states alike about its ESG policies. BlackRock and State Street testified before the Texas Legislature last month.

Regulators are demanding greater transparency too. In November, the Securities and Exchange Commission enacted a new rule requiring asset managers not only to disclose proxy votes but to categorize them in buckets like “environment or climate,” “diversity, equity and inclusion” or “other social issues.” If asset allocators in possession of such disclosures continue to invest or recommend the investment of capital into ESG-promoting funds, BlackRock and State Street can plausibly argue that they implicitly consented to the use of nonpecuniary factors.

That passes the buck of liability up to asset allocators. They shouldn’t be allowed to make such decisions on their clients’ behalf without express permission.

A combination of pro-disclosure policies and investor education can solve that problem. Lawmakers concerned about the use of ESG in capital markets need not ban it. They can simply require that capital owners be informed by their asset allocators whether their money is invested in an ESG-promoting fund and provide express consent to do so. Some capital owners will say yes, others will say no. But their dollars wouldn’t be used to advance social policies they don’t expressly support. If that is achieved, the ESG debate in the asset-management industry will be mostly over.

To see this article in its entirety and subscribe to others like it, choose to read more.

Source: A Solution Is in Sight for the ESG Controversy – WSJ

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online