By: Nicole Sganga – cbsnews.com – February 11, 2020

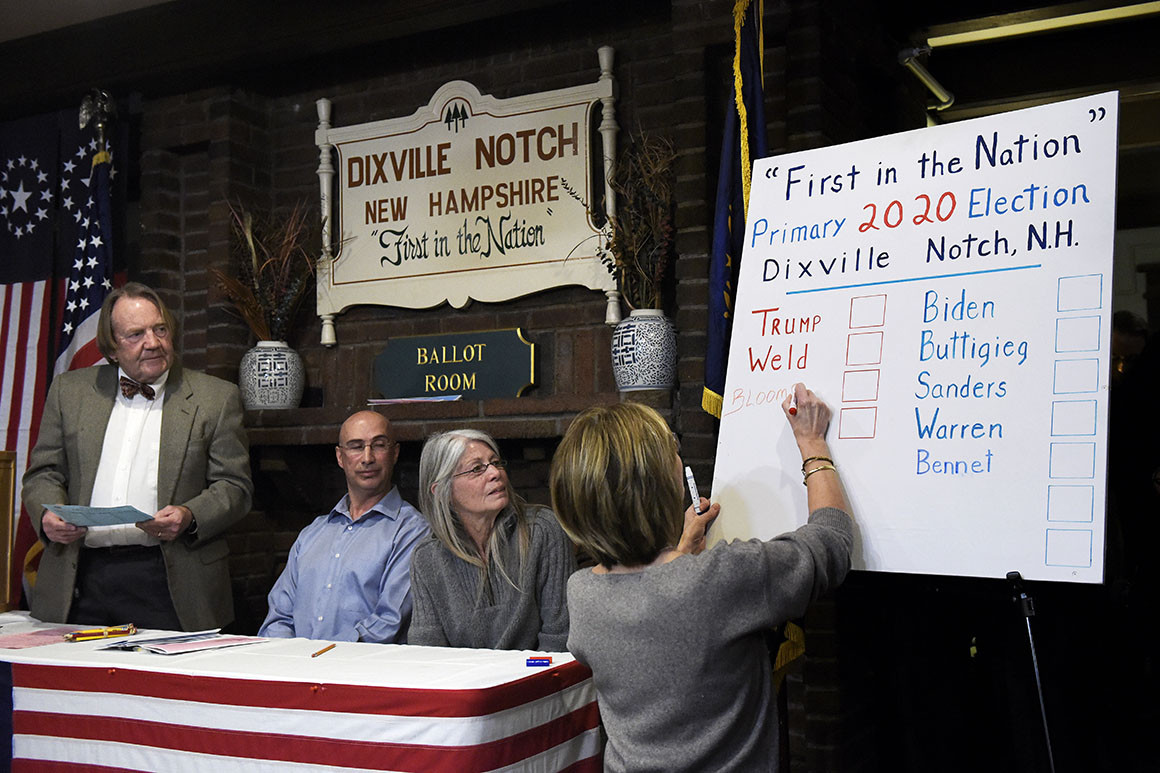

A week after Iowa’s caucus debacle, the nation casts its first votes of the 2020 primary cycle Tuesday in New Hampshire. After months of shopping for the right candidate at town halls and house parties, voters here will weigh in on the crowded Democratic field.

New Hampshire is celebrating 100 years of holding the “first in the nation” primary this year, but it’s not entirely clear how long the state will be able to hold on to that designation. In recent years, some in the Democratic Party have begun to complain that the state’s lack of racial diversity makes it ill-suited to be the first vetters of the presidential candidates.

The state has already taken some measures to protect its “first in the nation” status, passing legislation before the 1976 election that would prevent other states from preempting the state’s primary election. “The presidential primary election shall be held on the second Tuesday in March or on a date selected by the secretary of state which is seven days or more immediately preceding the date on which any other state shall hold a similar election,” the law reads.

The candidate next door

Candidates from next door have historically over-performed in the New Hampshire primary compared with national outcomes, a point Joe Biden brought up on Friday as he tried to downplay expectations for a better performance here after the “gut punch” he acknowledged getting from his fourth-place finish in Iowa.

With former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick’s late entry into the race, there are three candidates from neighboring states campaigning in New Hampshire for the Democratic nomination. The others are front-runner Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren.

This year, they may have a slight advantage, with neighboring volunteer reinforcements, New England commonalities and a familiar media market. But that hasn’t stopped Pete Buttigieg, of Indiana, and Amy Klobuchar, of Minnesota from surging in polls over the past few days.

Since 1952, when New Hampshire’s modern primary began, there have been 17 Democratic races. Seven of those included candidates from the Granite State’s three neighbors — Massachusetts, Maine or Vermont. In those races, New Hampshire’s neighbors have won six times. Additionally, two other times candidates from neighboring states finished in second place.

The Electorate

New Hampshire’s longtime secretary of state, Bill Gardner, has set his quadrennial 2020 primary turnout prediction at 420,000 voters (292,000 Democratic ballots and 128,000 Republican ballots.) If realized, that would be the most votes cast in a presidential primary featuring an incumbent president.

However, on a phone call with reporters Monday, New Hampshire Democratic Chair Ray Buckley said, “I don’t think anyone is predicting anywhere near the 2008 turnout. I think we will have a terrific turnout. It will certainly be higher than any other state in the entire nominating process. But there’s no indication we’ll match or be near 2008.”

In New Hampshire, undeclared or independent voters, who make up 42% of the current electorate, may pick up either a Democratic or Republican ballot on primary day. There are more independents this cycle compared to 2016 (38%), the majority coming from the Republican Party.

In 2016, Senator Bernie Sanders won the New Hampshire primary by over 22 points (56,838 votes). Hillary Clinton went on to win New Hampshire against Donald Trump by just 0.3% (less than 2,700 votes.) In New Hampshire alone, over 4,400 wrote in Senator Bernie Sanders’ name during the general election.

The Candidates

Bernie Sanders: While a double-digit victory seems nearly impossible this time around, the Sanders campaign hopes to drive turnout in all corners of the state – particularly on college campuses and in counties bordering Vermont.

State director Shannon Jackson says the campaign has made a point of interacting with voters across the state, even the less populated North Country. “We’ve been proud to have knocked on a ton of doors, going as high up as Pittsfield and as far left as Lancaster, really targeting areas for door-knocking, and bringing people into the process that have not ever had their doors knocked on before.”

The Sanders campaign, which won every town except three in 2016, says its approach is more “comprehensive” than “targeted,” placing nearly $6 million in advertisements in all three broadcast markets bordering New Hampshire.

The Vermont senator has made multiple tours of college campuses here, a “huge priority” for the campaign that calls its candidate the “oldest millennial.”

Joe Biden has predicted he’ll likely “take a hit” in New Hampshire. Biden has been dampening expectations for himself, and his campaign has been largely dark on the New Hampshire air waves, though the super PAC supporting him has been advertising on TV this week.

Biden boasts one of the strongest groups of surrogates here, including former New Hampshire Governor John Lynch, Former New Hampshire Congresswoman Carol Shea Porter and longtime Granite State political adviser, Billy Shaheen.

Biden senior adviser Terry Shumaker says he feels Biden can appeal to “all three” kinds of independent voters: independents that tend to vote Democrats, independents that tend to vote Republican and true independents. “I don’t see our market as just being independents,” he said conceding that “obviously, other candidates like Klobuchar and Buttigieg will have some appeal with independents, as well.”

Biden is the the only top-tier candidate who has not held public events in all 10 counties in New Hampshire, skipping Carroll County.

Since Pete Buttigieg came out on top of the field in Iowa with Sanders, he’s seen a rapid rise in the polls here and an influx of new volunteers this past weekend. His campaign in New Hampshire has 16 statewide office locations, placing some outposts in post-industrial New Hampshire that may feel forgotten: Berlin, Claremont, Conway.

“Relational organizing” is an oft-heard phrase from the campaign, which has hosted dozens of house parties over the past few weeks to foster “neighbor-to-neighbor” persuasion.

In his closing argument, Buttigieg rallied mayors and local leaders around his experience as mayor, to counter a recent attack ad from the Biden campaign.

Elizabeth Warren began door knocking early last summer in rural areas of the state, including Coos and Carroll County. The strategy attracted large crowds at rallies in more remote towns.

Warren’s campaign has the built-in advantage of a headquarters in Boston, just 45 minutes away from the New Hampshire state line. It has an active presence on college campuses, and across the southern part of the state. “There are certain areas of the state, college campuses for instance – Durham, Plymouth, Keene – that are important because Senator Sanders really rocked in those four years ago,” Warren supporter and DNC Councilwoman Kathy Sullivan told CBS News. “In the southern tier, those towns are heavy Republican but there are still a lot of Democratic voters and independents critical to any campaign.”

Warren’s team is widely recognized by lawmakers and local officials across the state as having one of the most well-organized, well-run operations in New Hampshire — complete with her famous selfie lines.

Amy Klobuchar has received the endorsement of the Union Leader, the Keene Sentinel and the Portsmouth Herald – a full sweep of New Hampshire local papers. Riding a post-debate bump, Klobuchar’s campaign picked up a whopping $3 million in fundraising since this weekend’s New Hampshire debate. Since her strong debate performance, tracking polls by CBS Boston/Boston Globe/Suffolk University and Emerson polling show a last-minute surge for Klobuchar, who has vaulted into third place.

Klobuchar’s campaign has been catering to the roughly half of undecided voters still making up their minds.

The Minnesota lawmaker has earned the support of a plethora of local leaders including Councilor Deborah Pignatelli, former Attorney General Joe Foster and Laconia Mayor Andrew Hosmer.

That surrogate surge helped Klobuchar “level the playing field” during her time away in Washington during the Senate impeachment trial of President Trump.

Andrew Yang began campaigning in New Hampshire two years ago, a move New Hampshire Democratic Party chair Ray Buckley says allowed the lesser-known candidate to gain traction on the national stage. Yang has recruited volunteer help from outside the state, attracting grassroots support from podcasters, youtube celebrities and self-funded full-time campaign volunteers who frequently travel with him across New Hampshire.

The campaign utilized successful Q3 and Q4 fundraising hauls to invest in digital and TV advertising, spending more than any other candidate in the Boston media market except Tom Steyer and Bernie Sanders. While struggling to fill open campaign positions in the fall, the upstart team now has 50 staffers and 10 offices.

Senior New Hampshire adviser Steve Marchand says Yang hopes earn the support of disaffected voters.

Last year Yang said his campaign was over if he didn’t perform well here: “If this does not come out of New Hampshire, it dies.”

Tom Steyer has visited the state fewer times than any top-tier presidential candidate, spending a sum total of 16 days in the Granite State.

Notably, the businessman has invested more than any candidate in New Hampshire’s airwaves, nearly $20 million overall.

But he’ll skip primary night here to launch a bus tour in the nation’s next early contest state: Nevada.

In late 2019, Michael Bennet abandoned all other state operations to double down on New Hampshire, announcing he would host 50 town halls in the final 10 weeks leading up the New Hampshire Primary. Joined by supporter James Carville, the Colorado senator met that goal this past weekend.

His focus on retail politicking mirrors the style of another Colorado senator and eventual winner of the New Hampshire primary, Gary Hart.

Deval Patrick buoys support and organizing manpower from the Bay State. Despite a slow start, Patrick’s campaign turned out 800 attendees at the annual Shaheen-McIntyre dinner. “I don’t think you have to hate Republicans to be a good Democrat,” Patrick said, in a departure from his rivals’ condemnation of Mitch McConnell and the present administration.

Patrick hosted the longest bus tour in this cycle’s primary — six days spanning all 10 counties during Iowa’s caucuses.

Tulsi Gabbard has all but moved to New Hampshire, renting a house on the outskirts of Manchester for several months leading up to the primary. Roughly half of the New Hampshire towns Gabbard has visited in New Hampshire backed Mr. Trump in 2016.

Her anti-war message attracts fans from both ends of the political spectrum, including former Trump strategist Steve Bannon and former Democratic Ohio Congressman Dennis Kucinich. But she has struggled to attract much of any support from mainstream Democratic voters who pick their party’s nominee.

Her campaign opened up its very first field office last month in downtown Manchester, operated by 50 full-time volunteers in New Hampshire.

The Republicans

[…]

The final weekend polling

[…]

The rules

[…]

The results

[…]

To see the remainder of this article, click read more.

Source: What to know about the 2020 New Hampshire primary – CBS News

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online