By: Daniel Huff – wsj.com – October 15, 202

Based on data from past closings, roughly 25% of the federal workforce could be permanently cut.

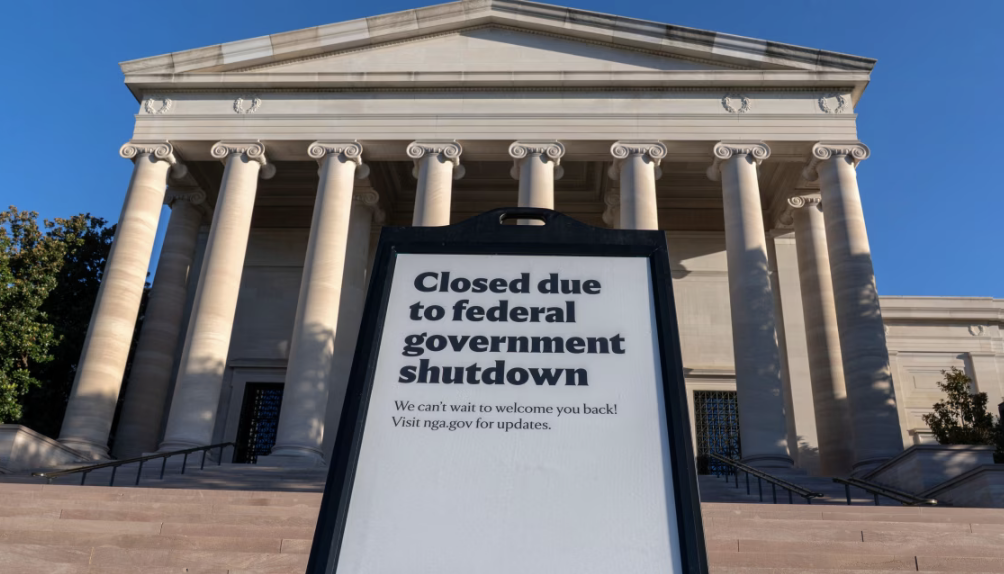

Here’s how it works. When Congress fails to fund the government by Oct. 1, the start of its fiscal year, the Constitution’s Appropriations Clause kicks in: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” Federal statutes back this up with serious consequences. Agencies can’t spend unauthorized money or accept free labor except in emergencies involving safety or property. Violations mean firings, fines and up to two years in prison.

Nevertheless, before 1980 agencies treated these restrictions loosely, keeping operations going during funding gaps while minimizing “nonessential operations.” Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti stopped that, ruling agencies must strictly comply with spending limitations in the Antideficiency Act.

Today, the Office of Management and Budget issues annual shutdown guidance. Agencies must submit “contingency plans” categorizing which employees are essential on a standardized worksheet. Only five narrow exceptions qualify: those protecting life and property, those necessary to the president’s constitutional duties, those performing legally mandated activities, those with funding outside the annual budget, and those authorized by other laws.

This creates a comprehensive map of what can be suspended without immediate risk. Since 1981, four major shutdowns have generated data about what government actually needs to function. Furlough rates have ranged from about 15% to 40%. The current 2025 shutdown sits at the low end, suggesting agencies have broadened their understanding of operational minimums.

Shutdowns let Congress run an experiment it would ordinarily never attempt: Close the whole thing down and see what breaks. This is what Elon Musk did at Twitter. He fired 80% of the staff, watched what broke, and restored only what proved necessary.

Conventional budget cuts start with everything and try to subtract, forcing agencies to prove positions aren’t needed while navigating political mine fields of lobbying and litigation. A shutdown inverts this logic. It starts with nothing and adds back only what is necessary. All positions are furloughed unless an agency can demonstrate an employee is essential to perform a core function. If services degrade, the agency can recall more workers, so the system self-corrects.

The 1996 Social Security Administration shutdown proves the point. SSA initiallykept only 4,780 employees to ensure benefit payments, furloughing 61,415 workers. Within days, they realized this wasn’t enough. They couldn’t handle phone calls from people needing Social Security cards or address changes. SSA recalled 49,715 employees for direct service work.

This approach—furlough broadly, identify failures, restore specific functions—is vastly more efficient than conventional budget cutting. Successive shutdowns have refined the data. The Office of Management and Budget produces detailed post-shutdown reports analyzing what worked and what didn’t, creating institutional learning that improves planning. For example, the fiscal 2014 shutdown generated data on which services generated outcry when suspended (national parks), which created safety risks (fewer inspections by the Food and Drug Administration), and which caused surprisingly little disruption.

Critics argue that a “nonessential” employee for shutdown purposes doesn’t mean unnecessary overall. Bureaucrats have bristled at the term as misleading and demeaning. But Congress itself has used this language in approving shutdown spending it described as needed to maintain an “essential level of activity.” Furthermore, the essential employee categories align closely with core government functions, namely public safety and the protection of property.

As a result, each funding impasse has collectively produced the world’s largest organizational efficiency study. Not a simulation or theoretical analysis, but a real-world test of which positions government can function without.

The data sitting in OMB’s files are a tested blueprint for smaller government, and the timing couldn’t be better. President Trump has said he wants to cut government and is leaning on OMB Director Russ Vought, who he noted was “of PROJECT 2025 fame.” That project, focused on slashing the bureaucracy, was headed by Paul Dans, an expert on the civil service who ran the Office of Personnel Management during Mr. Trump’s first term.

In the first Trump administration, Mr. Dans teamed up with personnel director John McEntee to fire bureaucrats and reclaim independent agencies for the president. Now it seems the president is motivated to replicate that success on a much bigger scale.

Based on shutdown data, roughly 25% of the federal workforce could be trimmed. OMB should review each agency’s contingency plan to determine which positions within the agency’s workforce are classified as non-essential. Start cuts there. If services degrade, restore positions. But begin with the government’s own assessment of what it can function without.

The test was already run. The administration just needs to read the results.

To see this article in its entirety and to subscribe to others like it, please choose to read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online