By: Daniel A. Bell – wsj.com – March 16, 2023

For a Chinese leader to have white hair would be a sign that he has left politics, either by force or voluntarily. When former Politburo member Zhou Yongkang appeared in court in 2015, the highest-ranking victim of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, his jet-black hair had turned completely white. Former president Jiang Zemin, on the other hand, continued to dye his hair for public appearances well into his 90s, a sign that he still exercised some power behind the scenes.

Of course, more recent factors than ancient tradition are also at play. The collective leadership system in China, developed in reaction to Chairman Mao’s arbitrary one-man rule, de-emphasizes individuality. Policy-making is supposed to be the product of collective deliberation among members of the standing committee of the Politburo, and individual leaders are not supposed to stick out too much. Here Hu Jintao was a master: His jet-black hair blended with other leaders who dyed their hair in an identical way, sending the message that he really was an equal among the eight other members of the standing committee.

Photo: Juliette Borda

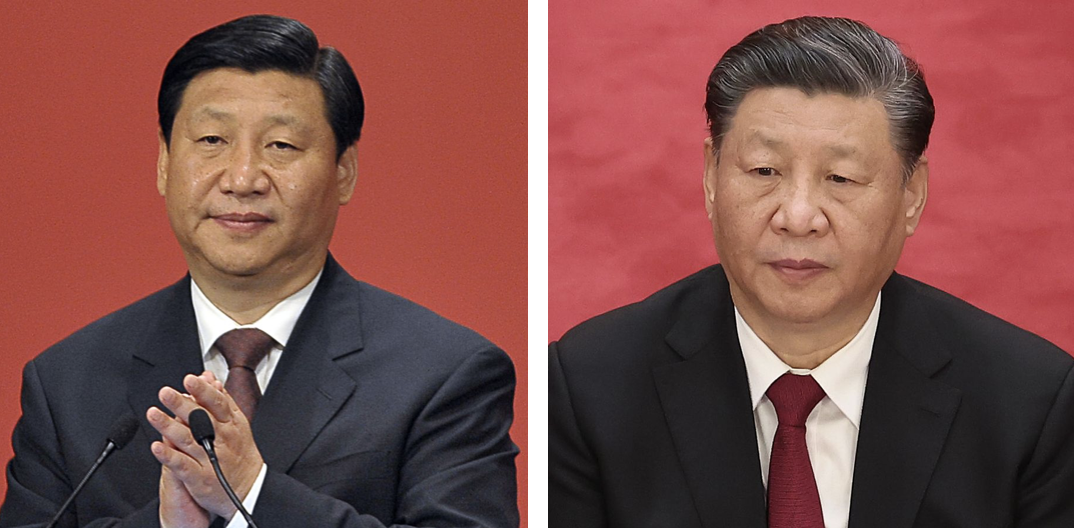

The collective leadership system under President Hu had a major drawback, however: Each top leader had de facto veto power over decisions, making it impossible to tackle vested interests that blocked necessary reforms. When Xi Jinping became president in 2012, the standing committee was reduced from nine to seven members and Mr. Xi took charge of newly established leading groups in charge of reform. Six years later, Chinese lawmakers approved changes to the constitution abolishing presidential term limits. Presidents Jiang and Hu had been limited to two five-year terms; last year, Mr. Xi was confirmed for a third term.

In 2019, Mr. Xi broke another long-standing political norm by appearing in public with streaks of gray in his hair. The topic was off-limits for the domestic media, but the Western media speculated that he meant to affirm his superior power relative to other members of the standing committee of the Politburo. Hung Huang, a media personality who grew up among political elites in Beijing in the 1960s and 1970s, remarks that leaders have traditionally dyed their hair black as a kind of “conformity to a single regimented style as a sign of unison and agreement…It’s one that Xi—who now clearly stands above everyone else—no longer needs.”

Does President Xi’s more “natural” appearance reflect the end of collective leadership? It’s too early to tell. What I can predict is that even if Mr. Xi proves to be a Putin-like leader who rules for decades with largely unchecked power, he will not let his hair turn completely white. The belief that white-haired people are not supposed to rule is perhaps the one article in China’s unwritten constitution that cannot be violated.

Political norms that influence the highest echelons of Chinese politics often filter down to lower levels of the bureaucracy. From 2017 to 2022, I served as dean of the faculty of political science at Shandong University, a post typically reserved for members of the Chinese Communist Party, given the political sensitivity of the work. I’m not a party member, or even a Chinese citizen; I’m a Canadian, born and bred in Montreal, without any Chinese ancestry. In my department, decisions needed to be approved by a group of leaders, including four vice-deans and three party secretaries. We half-jokingly referred to it as a system of collective leadership.

Like Mr. Xi and other leaders, our attire was neither too formal nor too casual, meant to suggest a commitment to work and closeness to the people. Not surprisingly, we were also constrained by the black-hair norm. Those of us with white hair needed to dye our hair black to project an image of energy and vigor in our efforts to serve the university. It would look strange if I dyed my hair black, so I dye it brown, the more natural-looking color given my pigmentation.

I confess, however, that my hair dyeing has earlier roots. It started when I was 39 and teaching at the City University of Hong Kong. My hair was rapidly graying, and my badminton partner—a remarkably fit graduate student—said that I looked like a distinguished professor. I wasn’t too happy about that, but my father and grandfather went gray in their 30s, and I was continuing the family tradition.

My Chinese mother-in-law at the time had other ideas. In general, she did not try to make me feel guilty for not living up to her traditional standards. She knew I was from a different culture and tolerated variations of ways of life within the family. With one exception: She was deeply disappointed when my hair began to turn gray, and she pressured me to dye it. I told her that male academics don’t dye their hair, but she didn’t care. “Even in the Cultural Revolution, she said, we—men and women—dyed our hair!”

Years later, when we moved to Beijing to start a new life there, I was relieved when I noticed that so many men, including professors, dyed their hair in mainland China. For the first time in a long time, I felt at home.

To see this article in its entirety and subscribe to others like it, choose to read more.

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online