By: William McGurn – wsj.com – May 24, 2021

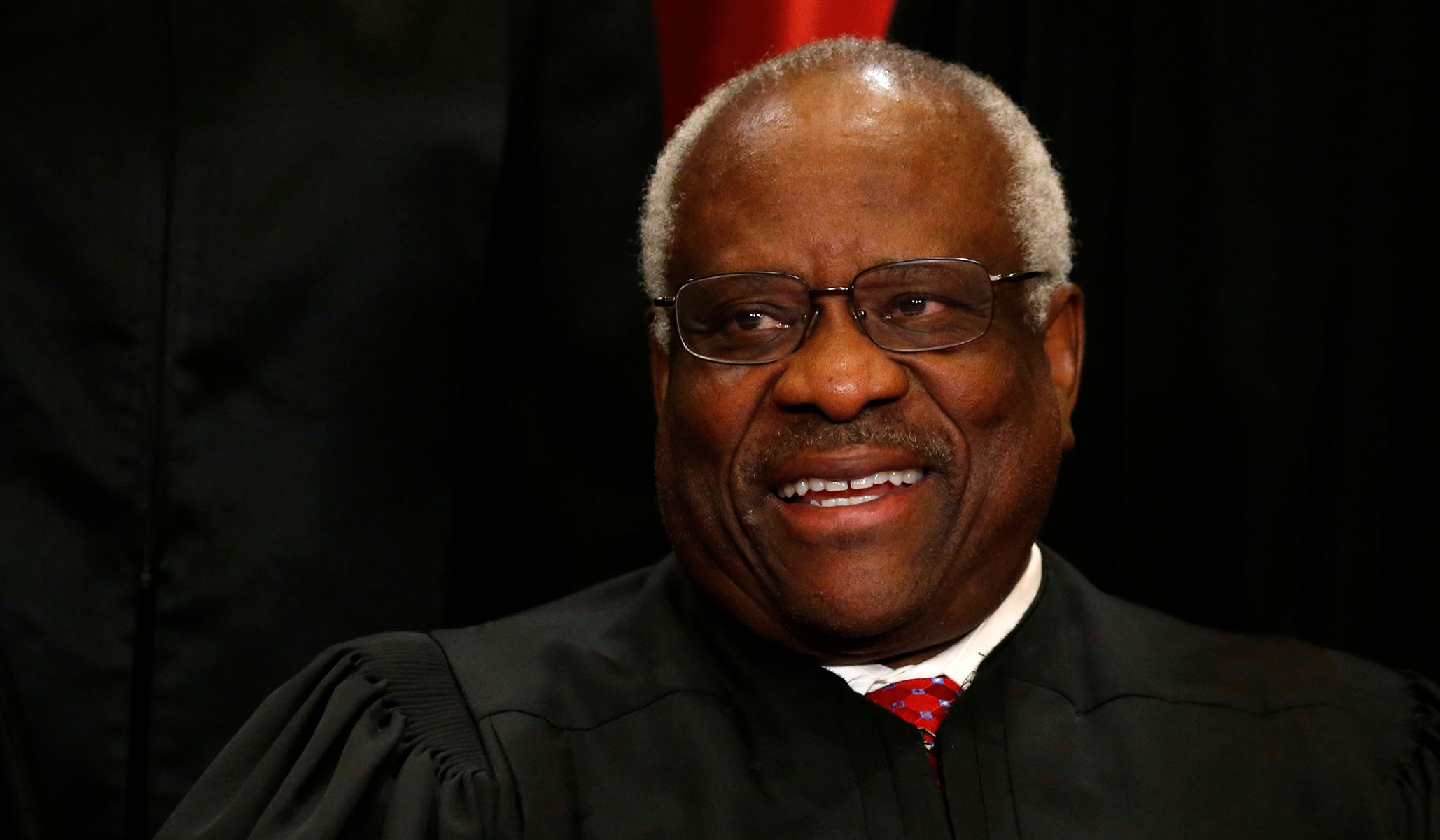

For Clarence Thomas, any chance he might become chief justice has long since passed. But at 72, he is coming into his own. For circumstances have now made it as plausible to speak of the Thomas court as the Roberts court.

The trigger was the replacement of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg with Justice Amy Coney Barrett. This move gave conservatives a 6-3 majority, depriving Chief Justice John Roberts of the ability to swing decisions to the liberal side—unless he manages to bring Brett Kavanaugh along with him.

This gives Justice Kavanaugh Joe Manchin-like powers over any case in which the chief might go south on his more conservative-minded colleagues. It’s a big change from the days when Justice Anthony Kennedy could easily move back and forth, here siding with conservatives to strike down speech limits in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), and there unearthing in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) a constitutional right for gay couples to marry.

For a while, Chief Justice Roberts looked as though he might become the new Anthony Kennedy. The chief pulled his own Kennedy in 2012, even before Justice Kennedy retired, when he saved ObamaCare by ruling that the individual mandate was a tax and thus constitutional. He has sided with the court’s liberal wing on other cases too, such as when he blocked the Trump administration’s bid to end the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. At the same time, the Roberts court has lately been shy to take up contentious issues from abortion to gun rights.

Enter Clarence Thomas. As Jan Crawford Greenburg noted in her 2007 book, “Supreme Conflict,” for many years Justice Thomas has been dismissed unfairly as Antonin Scalia’s sidekick. In fact, the men weren’t only brothers-in-arms but brothers—just listen to Justice Thomas’s tremendous eulogy for Scalia—whose significant disagreements on issues from natural law to deference to precedent helped each hone his own position while increasing their mutual respect.

Among the things these two great judges shared was an understanding that a majority opinion isn’t the only way to leave a mark. Like Scalia—whose greatest contribution may have been his fearless solitary 1988 dissent in Morrison v. Olson on the unconstitutionality of the independent counsel—many of Justice Thomas’s most powerful contributions haven’t come through majority opinions. Instead, they have come through dissents, concurrences and comments on denials of petitions to hear an appeal.

“His writings are often of the ‘emperor has no clothes’ variety where he argues that practice and Supreme Court precedent contradict the original meaning of the Constitution,” says John Yoo, a University of California, Berkeley, law professor who once clerked for Justice Thomas. “He isn’t really trying to win the case that day but is instead aiming for five, 10, 20 years ahead, when the court might come to its senses.”

Today the changes on the court have left Justice Thomas uniquely empowered. First, the new conservative majority now requires two defections for the liberals to triumph. Second, as the associate justice with the most seniority, it falls to Justice Thomas to assign the majority opinion when the chief justice comes down on the dissenting side. That presents Chief Justice Roberts with a dilemma: Since he can no longer dictate the outcome by himself, choosing the dissenting side without Justice Kavanaugh invites a Thomas majority opinion.

Take Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which the court recently decided to hear. It involves a Mississippi law that would limit most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. We don’t know if the chief voted to hear the case. But even if he didn’t, he now has an incentive to side with conservatives so he can write a majority opinion more narrow than what Justice Thomas would likely write.

Count this as a victory for Justice Thomas. Only 2½ years ago, he issued a tart dissent from the court’s decision not to consider another abortion-restriction case, accusing the court of ducking its responsibility. He called on the Roberts court to show some backbone: “Some tenuous connection to a politically fraught issue does not justify abdicating our judicial duty. If anything, neutrally applying the law is all the more important when political issues are in the background.” That’s the whole reason, he wrote, the Framers gave Supreme Court justices lifetime tenure.

He made similar remarks about the Second Amendment becoming “a disfavored right” after the court passed on several gun cases. As he rightly noted, this was when lower courts were flouting key Supreme Court rulings such as District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and McDonald v. Chicago (2010).

Now the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case about a New York gun law and another about a Mississippi abortion restriction. If the court does the right thing, it will take up one dealing with Harvard’s discrimination against Asian-Americans.

On the Supreme Court, it’s good to be chief. But right now it may be better to be Clarence Thomas.

To see this article and subscribe to others like it, choose to read more.

![]() Source: www.wsj.com/articles/god-save-the-clarence-thomas-court-11621893168

Source: www.wsj.com/articles/god-save-the-clarence-thomas-court-11621893168

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online