By: Ross Douthat – nytimes.com – April 23, 2019

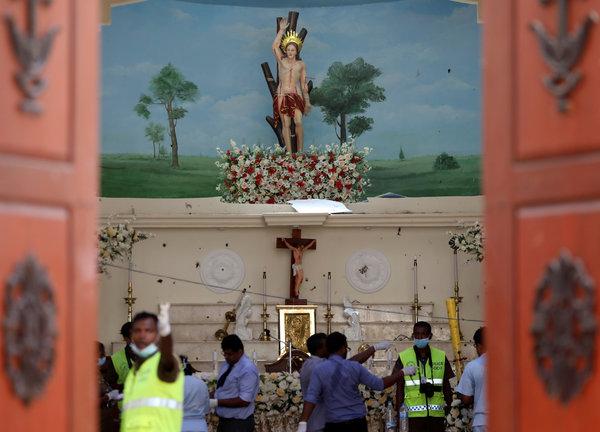

The murderous radicals who set off bombs and killed hundreds on Easter Sunday in Sri Lanka chose their targets with ideological purpose. Three Catholic churches were bombed, and with them three hotels catering to Western tourists, because often in the jihadist imagination Western Christianity and Western liberal individualism are the conjoined enemies of their longed-for religious utopia, their religious-totalitarian version of Islam. Tourists and missionaries, Coca-Cola and the Catholic Church — it’s all the same invading Christian enemy, different brand names for the same old crusade.

Officially, the Western world’s political and cultural elite does its best to undercut and push back against this narrative. The liberal imagination reacts with discomfort to the Samuel Huntingtonian idea of a clash of civilizations, or anything that pits a unitary “West” against an Islamist or Islamic alternative. The idea of a “Christian West” is particularly forcefully rejected, but even more banal terms like “Western Civilization” and “Judeo-Christian,” once intended to offer a more ecumenical narrative of Euro-American history, are now seen as dangerous, exclusivist, chauvinist, alt-right.

And yet there is also a way in which liberal discourse in the West implicitly accepts part of the terrorists’ premise — by treating Christianity as a cultural possession of contemporary liberalism, a particularly Western religious inheritance that even those who no longer really believe have a special obligation to remake and reform. With one hand elite liberalism seeks to keep Christianity at arm’s length, to reject any specifically Christian identity for the society it aims to rule — but with the other it treats Christianity as something that really exists only in relationship to its own secularized humanitarianism, either as a tamed and therefore useful chaplaincy or as an embarrassing, in-need-of-correction uncle.

You could see both those impulses at work in the discussion following the great fire at Notre-Dame. On the one hand there was a strident liberal reaction against readings of the tragedy that seemed too friendly to either medieval Catholicism or some religiously infused conception of the West. A few tweets from the conservative writer Ben Shapiro, which used phrases like “Western Civilization” and “Judeo-Christian” while lamenting the conflagration, prompted accusations that he was ignoring the awfulness of medieval-Catholic anti-Semitism, and also that his Western-civ language was just a dog-whistle for white nationalists.

But at the same time there was a palpable desire to claim the still-smoking Notre-Dame for some abstract idea of liberal modernity, a swift enlistment of various architects and chin-strokers to imagine how the cathedral (owned by the French government, thanks to an earlier liberal effort to claim authority over Christian faith) might be reconstructed to be somehow more secular and cosmopolitan, more of a cathedral for our multicultural times.

This seems strange, since as Ben Sixsmith noted for The Spectator, “it would never cross anyone’s mind to suggest that Mecca or the Golden Temple should lose their distinctively Islamic and Sikh characters to accommodate people of different faiths.” But an ancient, famous Catholic cathedral is instinctively understood as somehow the common property of an officially post-Catholic order, especially when the opportunity suddenly arises to renovate it.

As with monuments, so with beliefs. Consider the fascinating interview my colleague Nicholas Kristof conducted for Easter with Serene Jones, the president of Union Theological Seminary, long the flagship institution for liberal Protestantism. In a relatively brief conversation, Jones declines to affirm the resurrection, calls the Virgin birth “bizarre,” shrugs at the afterlife and generally treats most of traditional Christian theology as an embarrassment.

But is Jones a Richard Dawkins-esque scoffer or a would-be founder of a Gnostic alternative to Christianity? Hardly: She’s a Protestant minister and a leader and teacher for would-be Protestant ministers, who regards her project as the further reformation of Christianity, to ensure the continued use of its origin story and imagery (and its institutions, and their brands, and their endowments) for modern liberal and left-wing purposes. It’s another distilled example of the combination of repudiation and co-optation, the desire to abandon and the desire to claim and tame and redefine, that so often defines the liberal relationship to Christian faith.

If you aren’t a liberal Christian in the mode of Serene Jones, if you believe in a literal resurrection and a fully-Catholic Notre-Dame de Paris, this combination of attitudes encourages a certain paranoia, a sense that the liberal overclass is constantly gaslighting your religion. That elite will never take your side in any controversy, it will efface your beliefs and traditions in many cases and be ostentatiously ignorant of them in others … but when challenged, its apostles still always claim to be Christians themselves or at least friends and heirs of Christianity, and what’s with your persecution complex, don’t you know that (white) American Christians are wildly privileged?

This last dig is true in certain ways and false in others. It’s true that conservative Christians in the United States can fall into a narrative of martyrdom that doesn’t fit their actual position, true that the presidency of Donald Trump attests to their continued power (and their vulnerability to its corruptions!). On the other hand the marginalization of traditional faith in much of Western Europe is obvious and palpable, and the trend in the United States is in a similar direction — and residual political influence is very different from the sort of enduring cultural-economic power that a term like “privilege” invokes.

But if the equation of traditional Christianity with privilege has some relevance to the actual Euro-American situation, when applied globally it’s a gross category error. And so the main victims of Western liberalism’s peculiar relationship to its Christian heritage aren’t put-upon traditionalists in the West; they’re Christians like the murdered first communicants in Sri Lanka, or the jailed pastors in China, or the Coptic martyrs of North Africa, or any of the millions of non-Western Christians who live under constant threat of persecution.

One of the basic facts of contemporary religious history is that Christians around the world are persecuted on an extraordinary scale — by mobs and pogroms in India, jihadists and United States-allied governments in the Muslim world, secular totalitarians in China and North Korea. Yet as an era-defining reality rather than an episodic phenomenon this reality is barely visible in the Western media, and rarely called by name and addressed head-on by Western governments and humanitarian institutions. (“Islamophobia” looms large; talk of “Christophobia” is almost nonexistent.)

To see the remainder of this article, click read more.

Source: Opinion | Are Christians Privileged or Persecuted? – The New York Times

Listen Online

Listen Online Watch Online

Watch Online Find a Station in Your Area

Find a Station in Your Area

Listen Now

Listen Now Watch Online

Watch Online